Safeguards have been developed in the offline world to ensure that those with intimate knowledge of others do not exploit individual vulnerabilities and weaknesses through manipulation. However, online data aggregators and their related Artificial Intelligence (AI) firms with whom we have no relationship (such as a contract) have more information about our preferences, concerns, and vulnerabilities than our priests, doctors, lawyers, or therapists. We propose that governments should extend their existing offline protections against and standards regarding manipulation to also cover these data controllers. Presently, they enjoy knowledge and proximity of a very intimate relationship without the governance and trust inherent in similar offline relationships. We also propose several steps to protect citizens’ autonomy and decrease user deception. The ability of “data traffickers” and their AI partners to leverage the knowledge they have of almost every person on the Internet makes the scale of this public policy and political challenge worthy of Ministers and Heads of Government.

Challenge

A long standing tenet of public policy in both advanced and emerging economies is that when an economic actor is in a position to manipulate a consumer—in other words, in a position to exploit the relative vulnerabilities or weaknesses of a person to usurp their decision making—society requires their interests to be aligned and punishes acts that are seen as out of alignment with that person’s interests. In some relationships, such as those between priests-parishioners, lawyers-clients, doctors-patients, teachers-students, and therapists-patients, individuals are vulnerable to manipulation through the intimate data collected by the dominant actor. These types of relationships are governed such that the potential manipulator is expected to act in accordance with the vulnerable party’s interests. We regularly govern manipulation that undermines choice, such as when contracts are negotiated under duress or undue influence or when contractors act in bad faith, opportunistically, or unconscionably. The laws in most countries void such contracts.

When manipulation works, the target’s decision making is usurped by the manipulator to pursue its own interests, and the tactic is unknown by the target. Some commentators rightly compare manipulation to coercion (Susser, Roessler, and Nissenbaum 2019). In coercion, a target’s interests are overtly overridden by force and the target is aware of the threat and coercion. However, in manipulation the target’s choice is overridden subversively. These approaches both seek to overtake the target’s authentic choice but use different tactics. Thus, manipulation has the same goal as coercion combined with the deception of fraud. Offline, manipulation is regulated similar to how coercion and fraud are regulated: to protect consumer choice-as-consent and preserve individual autonomy.

Online actors such as data aggregators, data brokers, and ad networks not only can predict what we want/need and how badly we desire it, but can also leverage knowledge about when an individual is vulnerable to making decisions that are in the firm’s interests. Recent advances in hypertargeted marketing allow firms to generate leads, tailor search results, place content, and develop advertising based on detailed profiles of their targets. Aggregated data about individuals’ concerns, dreams, contacts, locations, and behaviors allow marketers to predict what consumers want and how best to sell it to them. Such data allow firms to predict characteristics such as moods, personality, stress levels, and health issues and potentially use that information to undermine consumers’ decisions. In fact, Facebook recently offered advertisers the ability to target teens when they are “psychologically vulnerable.”

This information asymmetry between users and data aggregators has sky-rocketed in recent years.

Proposal

Background

The data collection industry is not new. Data brokers like Acxiom and ChoicePoint have been aggregating consumer addresses, phone numbers, buying habits, and more from offline sources and selling them to advertisers and political parties for decades. However, the Internet has transformed this process. Users rarely comprehend the scope and intimacy of the data collection or the purposes for which it is sold and used.

One reason for this is that much of the data is collected in a non-transparent way and primarily in a manner that people would not consider covered by contractual relationships. Many Internet users, at least in developed countries, have some understanding that the search and e-commerce engines collect data about what sites they have visited and that this data is used to help tailor advertising to them. However, most have little idea of just how extensive this commercial surveillance is. A recent analysis of the terms and conditions of the big US platforms shows that they collect 490 different types of data about each user[1].

A recent study of 1 million web sites showed that nearly all of them allow third-party web trackers and cookies to collect user data to track information such as page usage, purchase amounts, and browsing habits. Trackers send personally identifiable information such as usernames, addresses, emails, and spending details. The latter allow data aggregators to then de-anonymize much of the data they collect (Englehardt and Narayanan 2016; Libert 2015).

However, cookies are only one mechanism used to collect data about individuals. Both little known data aggregators and big platforms collect huge amounts of information from cell towers, the devices themselves, many of the third-party apps running on a user’s device, and Wi-Fi access, as well as public data sources and third-party data brokers.

As the New York Times recently reported:

Every minute of every day, everywhere on the planet, dozens of companies—largely unregulated, little scrutinized—are logging the movements of tens of millions of people with mobile phones and storing the information in gigantic data files. The Times Privacy Project obtained one such file [which] holds more than 50 billion location pings from the phones of more than 12 million Americans as they moved through several major cities… Each piece of information in this file represents the precise location of a single smartphone over a period of several months…It originated from a location data company, one of dozens quietly collecting precise movements using software slipped onto mobile phone apps[2].

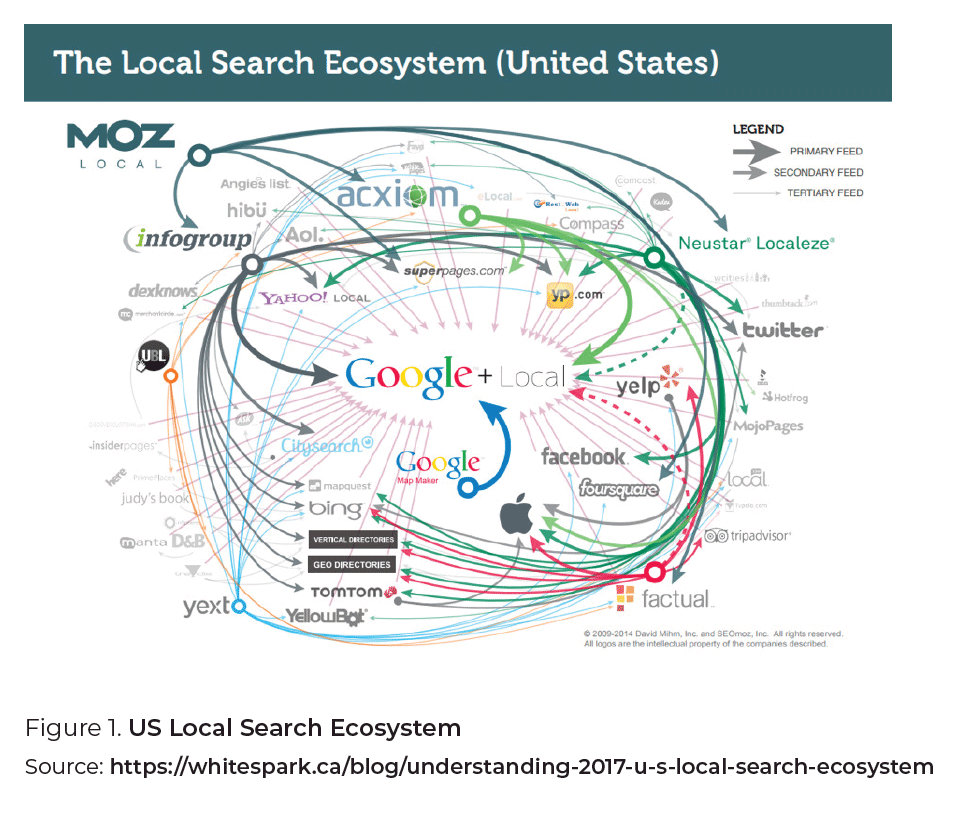

An indication of the scale and complexity of collecting and transferring user data among web sites can be gleaned from Figure 1. Devised by David Mihm, a noted expert on search engine optimization, it shows the data feeds that contribute to the US online local search ecosystem[3].

Data collection networks and markets like these, which are invisible to the vast majority of the people whose personal data are being collected, enable Cambridge Analytica (of the 2016 US Presidential election fame) to claim that it holds up to five thousand data points on every adult in the US[4].

Initial steps by governments

The correct governance for AI and its underlying Big Data has been discussed at national and dispersed international fora for several years, including efforts by the Council of Europe[5], the Innovation Ministers of the G7[6], the European Parliament[7], and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)[8]. In June 2019, the Group of 20 (G20) Trade Ministers and Digital Economy Ministers adopted a set of AI Principles[9] that draw from the OECD’s principles and discussion of proposals from G20 engagement groups[10]. These principles point to a more human-focused and ethical approach for guiding AI—but they are by necessity broad in tone and lack regulatory specifics.

The recent intimate data collection and transfiguration of many AI systems mimic vulnerable offline relationships, yet the safeguards found in offline relationships have not been put in place. Large AI systems, including platforms, accumulate data/ knowledge and consequently, power asymmetries that render consumers/citizens vulnerable to manipulation and exploitation. Furthermore, many of these firms operate with no relationship to their targets—indeed, many of the AI data aggregators are completely unknown to the individuals whose vast amounts of data they collect and manipulate.

This is contrary to several sections of the G20 AI Principles (2019). In particular, Section 1.1 (“Stakeholders should proactively engage in responsible stewardship of trustworthy AI in pursuit of beneficial outcomes for people… reducing economic, social, gender and other inequalities.”), Section 1.2 (” AI actors should respect the rule of law, human rights and democratic values, throughout the AI system lifecycle. These include freedom, dignity and autonomy, privacy and data protection, non-discrimination and equality, diversity, fairness, social justice, and internationally recognized labor rights.”), and Section 1.3 (“AI Actors should commit to transparency and responsible disclosure regarding AI systems… enable those affected by an AI system to understand the outcome; and… those adversely affected by an AI system to challenge its outcome based on plain and easy-to-understand information on the factors, and the logic.”)

Regulating manipulation to protect consumer choice is not novel. What is unique now is that the current incarnation of online manipulation divorces the intimate knowledge of targets and the power used to manipulate them from specific, ethically regulated relationships such as we usually find offline. Online, we now have a situation where firms with which we have no relationship have more information about our preferences, concerns, and vulnerabilities than our priests, doctors, lawyers, or therapists. In addition, these firms, such as ad networks, data brokers, and data aggregators, are able to reach specific targets due to the hypertargeting mechanisms available online. Nevertheless, we are not privy to who has access to that information when businesses approach us with targeted product suggestions or advertising. These data brokers enjoy the knowledge and proximity of an intimate relationship involving very personal aspects of our lives without the governance and trust inherent in such relationships offline. They clearly fail the transparency, stewardship, non-discrimination, autonomy, and fairness provisions of the G20 Principles.

Current approach to regulating online manipulation.

In the offline world, sharing information with a particular market actor, such as a firm or individual, requires trust and other safeguards like regulations, professional duties, contracts, negotiated alliances, and nondisclosure agreements. The purpose of such instruments is to allow information to be shared within a (now legally binding) safe environment where the interests of the two actors are forced into alignment. However, three facets of manipulation by data traffickers[11]—those in a position to covertly exploit the relative vulnerabilities or weaknesses of a person to usurp their decision making—strain the current mechanisms governing privacy and data. First, manipulation works by not being disclosed, making detection difficult and markets ill-equipped to govern such behavior. Second, the type of manipulation described here is performed by multiple economic actors, including websites/apps, trackers, data aggregators, ad networks, and customer-facing websites, which lure the targets. Third, data traffickers—who collect, aggregate, and sell consumer data—are the engine through which online consumers are manipulated, yet they have no interaction, contract, or agreement with those individuals.

These three facets—manipulation is deceptive, shared between actors, and not visible by individuals—render the current mechanisms ineffective for governing the behaviors or actors. For example, Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is strained when it attempts to limit a “legitimate use” of data traffickers or data brokers who seek to use intimate knowledge to market products and services. An individual has a right to restrict information processing only when the data controller has no legitimate grounds. GDPR falls short because legitimate interests can be broadly construed to include product placements and ads. Moreover, manipulating individuals has not yet been identified as diminishing the human rights of freedom and autonomy. One fix is to link manipulation more clearly to individual autonomy, which could be seen as a human right that would trump even the legitimate interests of data traffickers.

A first step forward—Policy goals

In general, the danger comes from using intimate knowledge to hypertarget and then manipulate an individual. The combination of individualized data and individualized targeting needs to be governed or limited, building on the 2019 G20 Principles on AI (2019). This is particularly necessary for the vulnerable, such as children, people with disabilities or mental health issues, the poor and naïve, and refugees.

1. Protect autonomy. Manipulation is only possible because a market actor, in this case a data broker, has intimate knowledge of what makes a target’s decision making vulnerable. The goal of governance would be to limit the use of intimate knowledge by making certain types of intimate knowledge either illegal or heavily governed. The combination of intimate knowledge with hypertargeting of individuals should be more closely regulated than blanket targeting based on age and gender. To protect individuals from manipulation in the name of “legitimate interests,” individual autonomy, defined as the ability of individuals to be the authentic authors of their own decisions, should be explicitly recognized within the AI Principles as a legal right.

2. Expand the definition of intimate knowledge. One step would be to explicitly include inferences made about individuals as sensitive information within existing regulations such as the GDPR (Wachter and Mittelstadt 2019). Sandra Wachter and Brent Mittelstadt have recently called for rights of access, notification and correction, not only for the data being collected but also the possible inferences about individuals drawn from the data. These inferences would then be considered intimate knowledge of individuals that could be used to manipulate them (e.g., whether someone is depressed based on their online activity). The inferences data traffickers make based on a mosaic of individual information can constitute intimate knowledge about who is vulnerable and when they are vulnerable. Current regulatory approaches only protect collected data rather than the inferences drawn about individuals based on that data.

3. Force shared responsibility. Make customer-facing firms responsible for who they partner with to track or target users. Customer-facing websites and apps should be responsible for who receives access to their users’ data—whether that access is by sale or by placement of trackers and beacons on their sites. Third parties include all trackers, beacons, and those who purchase data or access to users. Websites and apps would then be held responsible for partnering with firms that abide by GDPR standards, AI Principles, or new standards of care in the US. Holding customer-facing firms responsible for how their partners (third-party trackers) gather and use their users’ data would be similar to holding a hospital responsible for how a patient is cared for by contractors in the hospital or holding a car company responsible for a third-party app in a car that tracks your movements. This would force the customer-facing firm, over whom the individual has some influence, to make sure their users’ interests are being respected[12]. The shift would be to hold customer-facing firms responsible for how their partners (ad networks and media) treat their users.

4. Expand the definition of “sold.” Make sure all regulations include beacons and tracking companies in any capacity to notify if user data is “sold.”

5. Create a fiduciary duty for data brokers. There is a profound yet relatively easy to implement step to address this manipulation. The G20 and other governments could make their AI Principles practical by extending the regulatory requirements they have for doctors, teachers, lawyers, government agencies, and others who collect and act on individuals’ intimate data to also apply to data aggregators and their related AI implementations. Any actor who collects intimate data about an individual should be required to act on, share, or sell this data only if it is consistent with that person’s interests. This would force alignment of the interests of the target/consumer/user and the firm in the position to manipulate. Without any market pressures, data brokers who hold intimate knowledge of individuals need to be held to a fiduciary-like standard of care for how their data may be used (Balkin 2015). This would make data brokers responsible for how their products and services were used to possibly undermine individual interests.

6. Add oversight. With these economic actors well outside any market pressures, there are few pressures on firms to align their actions with users’ interests. Governments could add a GAAP-like governance structure to regulate data traffickers and ad networks to ensure individualized data are not used to manipulate. Recently McGeveran (2018) called for a GAAP-like approach to data security, where all firms would be held to a standard similar to the use of GAAP standards in accounting. However, the same concept should also be applied to those who hold user data in terms of how they protect the data when profiting from it.[13] Audits could be used to ensure data traffickers, who control and profit from intimate knowledge of individuals, are abiding by the standards. This would add a cost to those who traffic in customer vulnerabilities and provide a third party to verify that those holding intimate user data act in a way that is in the individuals’ interests and prevent firms from capitalizing on their vulnerabilities. A GAAP-like governance structure could be flexible enough to cope with market needs while remaining responsive and protecting individual rights and concerns.

7. Decrease deception. Finally, manipulation works because the tactic is hidden from the target. The goal of governance would be to make the basis of manipulation visible to the target and others: in other words, make the type of intimate knowledge used in targeting obvious and public. This might mean a notice (e.g., this ad was placed because the ad network believes you are diabetic) or a registry during hypertargeting to allow others to analyze how and why individuals are being targeted. Registering would be particularly important for political advertising so that researchers and regulators can identify the basis for hypertargeting. It should not be sufficient for an AI/ data aggregator to simply say, “I am collecting all this information in the users’ interests to see tailored advertising.” That is equivalent to a doctor saying, “I collect all this data about a patient’s health to ensure that only patients know about the prescriptions I give them.” Patients have to give permission for data to be collected and are entitled to know what data is involved (indeed, in many countries, patients formally own their health data), what tests have been conducted and their results, and what the diagnosis is. They are entitled to a second opinion on the data. Transparency and accountability online should be similar to that used offline. In other areas, where a lawyer or realtor or financial advisor has intimate knowledge and a conflict of interest (where they could profit in a way that is detrimental to their client), they must disclose their conflict and the conflict’s basis.

In the offline world, we have stressed the importance of clear relationships between people and those with intimate information asymmetries over them. Further, we have developed safeguards to ensure that those gaining positions of power do not exploit individual vulnerabilities and weaknesses. The issues posed by vast data collection and hypertargeted marketing and/or service delivery are a product of the global expanse of the Internet, social media, and AI platforms. Furthermore, the ability of “data traffickers” and their AI partners to leverage knowledge they have about almost every person on the Internet makes the scale of the public policy and political challenge worthy of Ministers and Heads of Government. As the growing “tech backlash” shows, there is political mobilization for change among citizens worldwide. The innovation of this “apply offline world rules to online players” approach is that it does not require governments to educate or force citizens to change behaviors or desires. It puts the ethical and regulatory onus clearly on the firms involved and holds them accountable.

Disclaimer

This policy brief was developed and written by the authors and has undergone a peer review process. The views and opinions expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the authors’ organizations or the T20 Secretariat.

References

Balkin, Jack M. 2015. “Information Fiduciaries and the First Amendment.” UCDL Review

49: 1183.

Englehardt, Steven, and Arvind Narayanan. 2016. “Online Tracking: A 1-Million-Site

Measurement and Analysis.” Accessed July 12, 2020. https://randomwalker.info/publications/OpenWPM_1_million_site_tracking_measurement.pdf.

G20 Principles on Artificial Intelligence. 2019. Narayanan. 2016. “Online Tracking: A

1-Million-Site Measurement and Analysis.” Accessed July 12, 2020. https://g20.org/en/media/Documents/G20SS_PR_First Digital Economy Taskforce Meeting_EN.pdf and

https://www.g20.utoronto.ca/2019/2019-g20-trade.html.

McGeveran, William. 2018. “The Duty of Data Security.” Minnesota Law Review 103:

1135.

OECD. 2019. “OECD Principles on AI.” Narayanan. 2016. “Online Tracking: A 1-Million-

Site Measurement and Analysis.” Accessed July 12, 2020. www.oecd.org/going-digital/ai/principles.

Scholz, Lauren Henry. 2019. “Privacy Remedies.” Indiana Law Journal: 653. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3159746.

Smith, Brad, and Harry Shrum. 2018. “The Future Computed.” Redmond: Microsoft

Corporation. Narayanan. 2016. “Online Tracking: A 1-Million-Site Measurement and

Analysis.” Accessed July 12, 2020. news.microsoft.com/cloudforgood/_media/downloads/the-future-computed-english.pdf.

Susser, Daniel, Beate Roessler, and Helen Nissenbaum. 2019. “Technology, Autonomy,

and Manipulation.” Internet Policy Review 8 (2).

Trade Union Advisory Committee to the OECD. 2019. “OECD Recommendation

on Artificial Intelligence Calls for a ‘Fair Transition’ Through Social Dialogue.”

Narayanan. 2016. “Online Tracking: A 1-Million-Site Measurement and Analysis.” Accessed

July 12, 2020. https://tuac.org/news/oecd-recommendation-on-artificial-intelligence-calls-for-a-fair-transition-through-social-dialogue.

Trade Union Advisory Committee to the OECD. 2020. “Is Artificial Intelligence Let

Loose on the World of Work?” Narayanan. 2016. “Online Tracking: A 1-Million-Site

Measurement and Analysis.” Accessed July 12, 2020. https://medium.com/workersvoice-oecd/is-artificial-intelligence-let-loose-on-the-world-of-work-966c86b975e8.

UNI Global Union. 2018. Ten Principles for Workers’ Data Privacy and Protection.

Nyon, Switzerland: UNI Global Union.

Wachter, Sandra, and Brent Mittelstadt. 2019. “A Right to Reasonable Inferences:

Re-Thinking Data Protection Law in the Age of Big Data and AI.” Columbia Business

Law Review.

Appendix

[1] . See the publicly available data at https://mappingdataflows.com

[2] . See the publicly available data at https://mappingdataflows.com “One nation, tracked An investigation into the smartphone tracking industry from Times Opinion” https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/12/19/opinion/location-tracking-cell-phone.html?searchResultPosition=8

[3] . https://whitespark.ca/blog/understanding-2017-u-s-local-search-ecosystem

[4] . See “MPs grill data boss on election influence,” 27 February 2018 https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-43211896

[5] . https://rm.coe.int/algorithms-and-human-rights-study-on-the-human-rights-dimension-of- aut/1680796d10

[6] . https://g7.gc.ca/en/g7-presidency/themes/preparing-jobs-future/g7-ministerial-meeting/chairs- summary/annex-b

[7] . Directorate-General for Parliamentary Research Services (European Parliament), A governance framework for algorithmic accountability and transparency. Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2019/624262/EPRS_STU(2019)624262_EN.pdf

[8] . https://www.oecd.org/going-digital/ai/principles

[9] . Annex to G20 Ministerial Statement on Trade and Digital Economy. Available at https://www.mofa.go.jp/ files/000486596.pdf

[10] . For instance, see Paul Twomey, “Building on the Hamburg Statement and the G20 Roadmap for Digitalization: Toward a G20 framework for artificial intelligence in the workplace.” Available at https://www. g20-insights.org/policy_briefs/building-on-the-hamburg-statement-and-the-g20-roadmap-for-digitalization-towards-a-g20-framework-for-artificial-intelligence-in-the-workplace

[11] . Lauren Scholz first used the term data traffickers, rather than data brokers, to describe firms that remain hidden yet traffic in such consumer data (Scholz 2019).

[12] . It is ironic that data traffickers can currently sell data to bad actors but just cannot have their data stolen by those same bad actors.

[13] . McGeveran calls for a GAAP-like approach for data security. Here, we suggest the same idea for data protection, where standards are set, and third parties must certify they have been conformed to (McGeveran 2018).