This Policy Brief is offered to the Saudi T20 process, as a recommendation to the G20 in 2020.

Challenge

In less than six months, a novel coronavirus – SARS-CoV2 – that causes a disease called Covid-19, has infected millions of people, caused hundreds of thousands of deaths, disrupted the social congress of most of humanity, and plunged the world into the deepest economic depression in a century.

The pandemic has triggered an unprecedented surge of scientific collaboration in efforts to understand how it overcomes our immune systems; to develop therapies to mitigate and cure the disease; and to craft a vaccine to protect us against infection.

It has prompted displays of heroism and deep commitment by medical and nursing personnel, and other frontline workers around the world, many of whom have become infected after being asked to serve without proper protection. It has led to extraordinary displays of solidarity as persons of wealth have donated billions; pensioners have volunteered contributions they can scarcely afford, and neighbours have reached out to those in need, to provide solace and care.

And it has amplified some of the worst of human vices, abuse of women and children, pettiness and bitterness, vicious slander and theories of wild conspiracy.

Most of humanity has accepted the privations of lockdowns – isolating households even from family members and neighbours – with remarkable equanimity. Hunger has triggered outbursts and breakouts; glitches in financial support deployed with speed by those governments that could, have caused fear and anger; but people of all cultures and countries have displayed remarkable equanimity.

The weakness of our systems of prevention, and rapid response to epidemics and other disasters have been disclosed and the political class has been wrongfooted. Some national leaders recovered well and rose to the occasion, addressing the challenge in their own societies, supressing the curve of infection and calling for and contributing to a global response. A few have displayed smallness of spirit, and wholly improper narcissism. Human strength and weakness have been everywhere on display, and greater challenges lie ahead.

On April 14, the IMF’s World Economic Outlook projected real global GDP growth of -3 percent; that of the advanced economies of –6.1 percent; and the emerging and developing economies of – 1 percent. Real GDP growth in the European Union was projected as –7.1 percent Some ten days later, the median estimate of the European Central Bank for the EU was – 9 percent.

Something of the order of $10 trillion in emergency support will be needed to avoid the world being trapped in this depression. It matters greatly how the money is provided and disbursed. IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva’s energetic advocacy of global economic solidarity has led the G20 and the Paris Club to suspend debt service payments for the poorest countries and to call on private creditors to do the same. This debt standstill will have to be followed by debt restructuring, and the IMF will need to issue new SDRs to respond on the necessary scale. Meanwhile, the EU has announced that it will host an international online pledging event to strengthen global preparedness and ensure adequate funding to develop and deploy a vaccine against COVID-19.

Thankfully, the Presidents of the EU Council and Commission have also called on the G7 to take the lead, with the G20 and the key international organisations, in building the post-“COVID-19 crisis world”.

Proposal

The phrase is both important and evocative. We need a new world system, with structures that are fit for purpose in a digital age in which 7.8 billion and rising, increasingly urbanised, humans are changing the climate, polluting the oceans and the atmosphere and pushing up against the planetary boundaries that we cannot transgress without risking the survival of our, and many other, species.

While it has been clear for over two decades – since the Asian and Emerging Markets’ crises of 1998-99 – that unfettered globalisation and the increasing financialization of our economies, widening inequalities within societies and the pursuit of status through excessive consumption and accumulation, are neither equitable nor sustainable, it has taken this pandemic to bring home the need for radical restructuring of the paradigm within which we conduct ourselves.

Perhaps not since Bretton Woods has there been such a moment. Almost every thoughtful person, whatever her ideological preferences, knows that reverting to the world we inhabited before the virus struck, is not the best way of spending the $10 trillion dollars that we shall have to provide through central banks, and monetize fully, if we are to recover from this crisis.

The fragility of the international order and the global financial system, the unsustainable ratio of aggregate debt-to-GDP before the pandemic, the quantum of government bonds with negative yields, the enormous inequality of wealth and income in too many national societies, and the lack of trust in political and economic institutions in almost all the advanced economies, make it clear that a new paradigm is essential. No rational human being can argue that we need to rebuild what has been, and is being, destroyed.

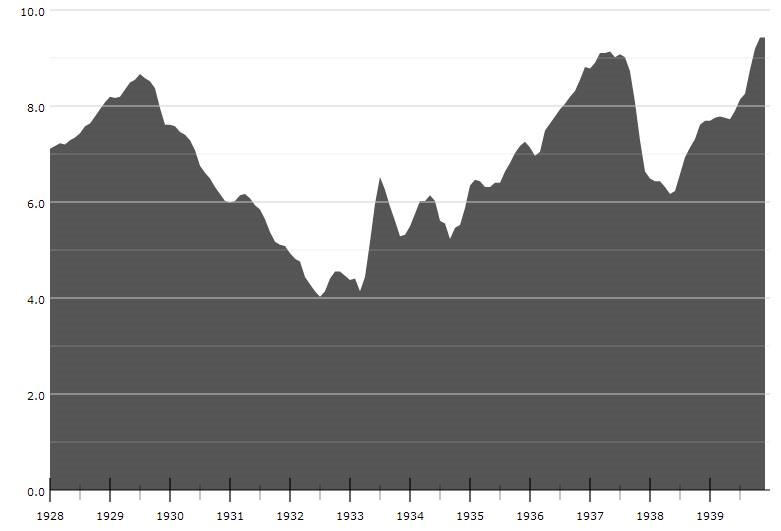

We were at a similar moment during the Great Depression. By 1932-33 industrial production had plunged.

By the time of Bretton Woods, just over a decade later, Keynes had written The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936), arguing that as aggregate demand determined the overall level of economic activity, depressed demand would lead to prolonged unemployment. To restore the appropriate level of demand, he argued, counter-cyclical fiscal and monetary policy were needed. Roosevelt had crafted the “New Deal” on that premise, only to have the war intervene. The crisis occasioned by the Depression and the war, and the surge in demand occasioned by the U.S. war effort, permitted a commitment to a new global paradigm that would not have been possible a decade earlier. And thus, was born the age of affluence, first in the West, and then more widely.

The problem is that the paradigm that we require for our present task has not yet been defined!

To cite Antonio Gramsci, in 1930:

“La crisi consiste appunto nel fatto che il vecchio muore, e il nuovo non può nascere: in questo interregno si verificano i fenomeni morbosi piú svariati.” Antonio Gramsci, (1930), Quaderni del carcere, ‘Ondata di materialismo’ e ‘crisi di autorità’, vol. I, quaderno 3, p. 311.

[“The crisis arises from the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot [yet] be born; in this interregnum, many morbid symptoms appear.”]

The task of a leader is to lead – to define a vision, and a strategic path to reach it; to attract widespread and deep support that encourages others to commit to helping to realise it; and to create an environment that will enable implementation of the strategy and achievement of the vision.

We are at a moment akin to that of Bretton Woods, on an even larger scale. The time cries out for those who have a vision of an equitable, sustainable future that will allow almost eight billion people to live in harmony with one another, and with the earth system in which we are embedded.

Envisioning a future defined by equity, sustainability and security; defining the pathways to achieving it; and using the funds that will have to be printed and monetized to escape from the Depression into which this pandemic has cast us, to create an equitable, secure and sustainable world, is the task of the age. It is conceptually simple, albeit that its execution will be challenging in a fractured world.

We need a coherent narrative that defines this vision and the means to achieve it, capitalising on the reality of our common humanity hammered home by the trauma wrought by SARS-CoV2, and our ability to rise above the threat and work to create a world that will be resilient against future disasters. The global scientific community is demonstrating that ability in fields as varied as theoretical physics, space exploration and the biomedical research needed to address this pandemic.

We must show that we can transform our social systems to ensure that the economy advances the wellbeing of society, encouraging innovation and reward without rent-seeking; and that the instruments that we employ for energy, mobility, industry, construction, residence and agriculture become integrated circular systems that will allow us to create a world fit for both our, and future, generations.

Showing that, by building effective accountability into our political systems, and strengthening the institutions that are essential for effective, constructive international cooperation, will restore trust, and enable cooperation for the collective good, while retaining the creative merits of competition and containing conflict. It’s a task for heroes, and a time to summon the will to undertake the quest!