Promoting high-quality fixed and mobile broadband for all (at an affordable price) is an important enabler to the digital transformation of society as a whole and to closing the digital divide. This has been even more so during the pandemic, since broadband access has been a crucial enabler for remote work, distance learning, telemedicine, and e-commerce.

It has always been challenging to provide broadband access to all at an affordable price. The pandemic, overall geopolitical tension, and Russia’s unprovoked aggression in Ukraine have exacerbated supply chain disruptions in ways that make this even more difficult and potentially expensive.

Promotion of broadband deployment, adoption, and use are all important for both fixed and mobile broadband; however, different policy levers are needed in each case, on both the supply and demand sides. The market will not always deliver complete solutions; consequently, there is often a role for regulation, targeted industrial policy, and public finance. Promotion of competition, combined with prompt and efficient provision of access to resources such as electromagnetic spectrum and access to land and rights of way, can be particularly important.

As regards public finance, as the G20 countries and others now seek a future-proof, sustainable, and equitable recovery, new funding vehicles need to be considered. Judicious use of recovery funds may be appropriate, as well as taking account of expected new tax revenues due to OECD/G20 BEPS corporate tax reforms.

Challenge

Widespread availability and use of high-quality broadband are key to achieving a more prosperous and equitable society. Its importance is explicitly recognized as a part of UN Sustainable Development Goal 9 (Goal 9 or SDG 9), which seeks to “build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation,” primarily through Target 9.c, which aims to “significantly increase access to ICT and strive to provide universal and affordable access to internet in LDCs by 2020.” Given the centrality of internet access to modern life, it has become clear that it is unacceptable for anyone to be involuntarily excluded due to the high cost or lack of availability of broadband internet access with acceptable quality parameters.

There are many indications that the adoption of broadband contributes to prosperity. Multiple studies have found that an increase in the broadband penetration rate can lead to a rise in GDP (Röller & Waverman, 2001), (Czernich, Falck, Kretschmer, & Woessmann, 2011), (Campbell, Castro, & Wessel, 2021). As more individuals gain effective access to the network, the value grows for all users due to network effects.

Broadband contributes to the broader economy in many different ways. It can promote innovation, enabling the creation and use of a wide range of Internet-based services. This lifts the overall economy and boosts competitiveness. (Marcus, Porciuncula, Reisch, & Weber, 2021) More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that broadband access is a crucial enabler for remote work (Marcus, Petropoulos, & Aloisi, 2022), distance learning, telemedicine, and for e-commerce.

As the G20 countries seek to move beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a particular need to ensure that the recovery is sustainable, equitable, and future-proof. High-capacity broadband infrastructure is a key enabler to a forward-looking recovery.

Both fixed and mobile broadband technologies can be deployed to close the digital divide. Fixed broadband infrastructure is the foundation of this process in many countries, but mobile broadband is an important complement in all countries. In some G20 countries, mobile broadband will be the primary means of serving parts of the national territory for the foreseeable future.

It is important to distinguish between deployment (as characterized by the coverage of fixed and mobile broadband networks), adoption (the fraction of the public that subscribes or has access to services), and the usage of broadband service.

Adoption and use are dependent on deployment. Many different technologies are used to achieve deployment, including not only fixed telecommunication networks and mobile networks but also cable television networks, fixed wireless networks, and satellite networks of various forms. Our primary focus in this paper is on fixed telecommunication and mobile networks because these are by far the most common. Still, other technologies can also have their place, especially to serve remote or low-density regions.

Unfortunately, even in highly developed countries, the cost of deploying high-speed fixed broadband to the most costly portions of the national territory is typically greater than the price many consumers are willing or able to pay. Population density, topography, and availability of existing telecoms or cable television infrastructure play a significant role in determining costs, even more so for the fixed network than the mobile network. The economics of deployment tend to be favorable in large cities with good access to global connectivity but challenging in mountainous or remote regions, on islands, or in land-locked countries far from submarine cables.

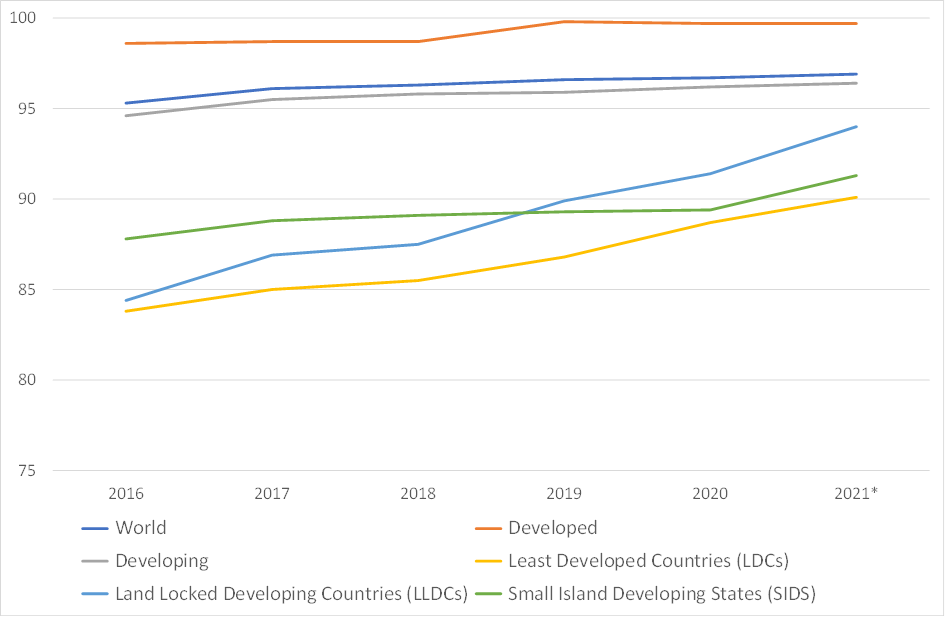

Deployment of mobile networks is less problematic than fixed, but Figure 1 clarifies that there are still gaps. Coverage of mobile networks is close to 100% in developed countries, somewhat lower in developing countries, but substantially worse in the Least Developed Countries (LDCs), in Land Locked Developing Countries (LLDCs), and Small Island Developing States (SIDS) (International Telecommunications Union (ITU), 2021). In many parts of the world, high oligopoly prices for access to submarine cables, bloated fees for access to cable landing stations, and inflated costs for leased lines to access the cable landing stations can impede internet access or inflate its price, and this is a particular concern for land-locked countries (researchICTafrica, 2016).

It is worth noting, moreover, that not all coverage corresponds to high performance, robustness, or reliability. Even so, country averages for basic mobile coverage exceed 90% in most countries (but are far worse for fixed coverage).

Figure 1. Percent of population covered by a mobile cellular network.

Source: (International Telecommunications Union (ITU), 2021), Bruegel calculations.

* – Data for 2021 is estimated because the year was not complete when the data was collected.

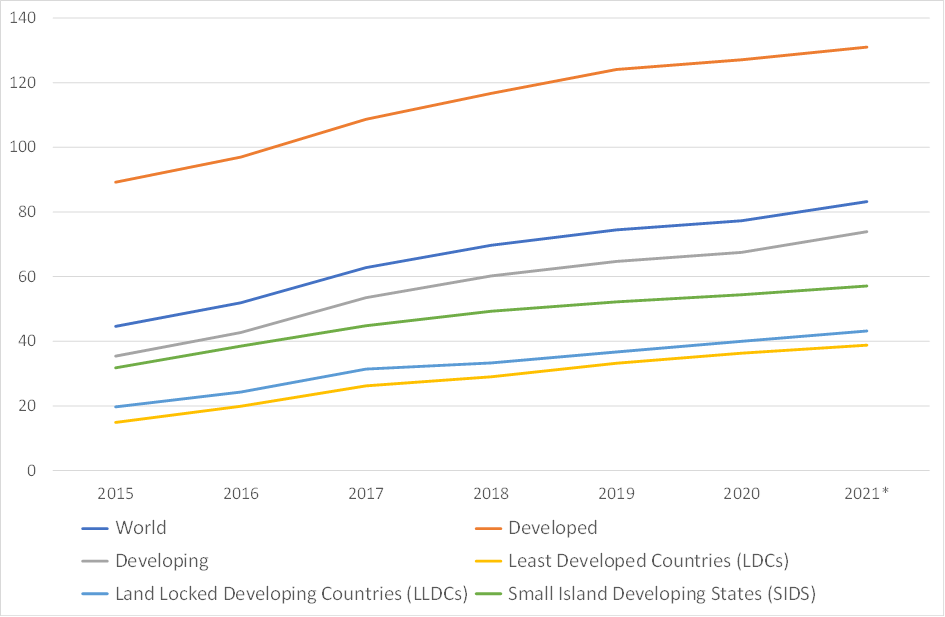

The situation is much worse for adoption[1] than for deployment. Only about 40% of inhabitants of land-locked countries or Least Developed Countries (LDCs) have a mobile subscription (see Figure 2)[2].

Figure 2. Active mobile broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants.

Source: (International Telecommunications Union (ITU), 2021), Bruegel calculations.

Once broadband service has been taken up, there is still no assurance that it will be used efficiently, effectively, or securely. Survey results in multiple countries demonstrate that lack of skills, together with a lack of perceived value of internet services (which likely reflects in large part a lack of skills), is the most severe impediment to adoption for many users (for the European Union, see Figure 3 in Section 2.2).

In nearly all countries, achieving full coverage and widespread adoption together with extensive use requires public policy interventions.

Proposal

Different countries face different challenges in achieving broadband deployment, adoption, and use; however, they also bring different strengths to the task. Among the dimensions on which countries differ are (1) disposable income; (2) the degree of digital competence on the part of the public; (3) population density and dispersion; (4) physical topography—mountains, islands, distance if relevant to submarine cables; (5) existing coverage of fixed, mobile and cable networks; and (6) physical characteristics of deployed networks (for instance, the length of copper sub-loops from the street cabinet to the residence).

These considerations and others were already reflected in OECD’s Recommendation on Broadband Connectivity (OECD, 2012) and in studies that supported its revision in 2021 (Marcus, Porciuncula, Reisch, & Weber, 2021); (Fanfalone, 2022). However, all of this must now be understood in a global context that has been profoundly altered by two transformative events: the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The pandemic has made clear the value of broadband internet access as an enabler for e-commerce, for work from home (Marcus, Petropoulos, & Aloisi, 2022), and for a wide range of additional business-to-consumer (B2C), business-to-business (B2B), and e-government services. At the same time, the pandemic has put stress on global value chains.

The UN General Assembly and an OSCE mission criticized Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine. (Benedek, Bílková, & Sassòli, 2022) Russia’s unconscionable conduct has contributed to the decoupling of global value chains for technology-based goods (Grzegorczyk, Marcus, Poitiers, & Weil, 2022) and services (Marcus, Poitiers, & Weil, 2022), including telecommunication equipment and other ICTs. This exacerbates stresses on global value chains that had already been present due to strategic competition between the United States and China and further complicates the global deployment of broadband internet access in many different ways (see Section 2.3.2).

If the challenges differ from one country to the next, then public policy responses need to be different. Good institutional design is fundamental for any interventions that are taken. Beyond this, deployment challenges must mainly be addressed using supply-side interventions. A well-tuned regulatory policy can greatly promote broadband deployment on the supply side (see Section 2.1). Adoption and usage challenges must mainly be addressed using demand-side interventions (Section 2.2), focusing on education and training as an ongoing lifelong learning activity. Public and private financing of broadband infrastructure can constitute a different form of supply-side intervention (which we discuss in detail in Section 2.3 because it is critical to the policymakers who are the key audience of this report).

Recommendations appear at the point in the text at which they are relevant. Unless otherwise noted, the recommendations are generally independent of current circumstances, including (1) the continuing presence of a pandemic and (2) the re-emergence of kinetic warfare in Europe. Section 3 provides a concise summary of the recommendations, while the appendix provides a complete recapitulation of all the recommendations.

Proper institutional design is important for both supply- and demand-side measures. No public policy intervention strategy will likely be effective unless the government draws a clear organizational distinction between industrial policy and regulation. Industrial policy should be administered by the government, typically by a ministry, and should be subject to political accountability to the public (e.g., voters). Regulation, however, seeks to impartially administer detailed policy initially set at the political level. Regulation must be insulated from political pressure so as to ensure that rules are administered fairly and impartially (OECD, 2011). The ultimate accountability of the regulator is not to the voters but to the courts.

At the industrial policy level, formulating a national strategic plan for fixed and mobile broadband deployment and adoption can play a positive role in achieving good outcomes (Marcus, Porciuncula, Reisch, & Weber, 2021, pp. 36-37).

The maintenance of appropriate and internationally comparable statistics on broadband deployment, adoption, and use is crucial. (Marcus, Porciuncula, Reisch, & Weber, 2021, pp. 38-39) Coherent policy must rest on a clear understanding of where gaps are to be found and where progress is (or is not) being made. Statistics of broadband coverage can be particularly challenging due to (1) lack of precise definitions and (2) difficulties in assessing the degree to which coverage overlaps between distinct network networks.

Reliable periodic surveys of the public can also play a key role in determining (1) the number of individuals per 100 inhabitants who do not have access to fixed or mobile broadband and (2) the reasons why inhabitants do not have access to a fixed or mobile broadband communication service.

Recommendation 1. Ensure the collection of reliable statistics on network deployment, adoption, and usage, conducting surveys as appropriate.

2.1 Supply-side regulatory and policy measures

Reliance on market mechanisms to ensure broadband deployment generally promotes (in the absence of market distortions) competition, innovation, interoperability, and consumer choice; however, there are few countries (if any) where placing sole reliance on market mechanisms will result in full coverage for all consumers at reasonable prices. As already noted, the cost of deploying high-speed fixed broadband to the most expensive portions of the national territory is typically higher than the price many consumers are willing or able to pay. There may also be gaps in mobile coverage. Consequently, there is usually a role for public policy to play on the supply side; these public policy interventions must be carefully managed to avoid introducing economic distortions.

Problematic geographic coverage gaps are more likely in regions (1) that do not already have good fixed network coverage for building on, or in regions that (2) have low population density, or (3) mountainous regions, (4) islands, or (5) low-income land-locked countries.

Regulatory policy measures can help close the deployment gap. There can also be a role for targeted public subsidy to ensure full deployment and full adoption by the poor and the disadvantaged. We take up these two public subsidy approaches in Section 2.3.

For fixed networks, typical regulatory policy interventions include (1) promotion of competition (Section 2.1.1), (2) implementation of alternative ownership or operation structures (Section 2.1.2), and (3) measures to reduce deployment costs, thus shifting the balance between cost and revenue (Sections 2.1.2 and 2.1.3). For mobile networks, prompt spectrum assignment is important, as well as various forms of infrastructure sharing (Section 2.1.4).

All of these are best implemented in a context of technological neutrality where the government does not seek to promote one specific technology in preference to another needlessly. Cable television, a high performance infrastructure that is ignored in much of the literature on broadband network deployment, is a case in point. Cable is the majority broadband provider in the USA and Canada [G20 countries] and provides full coverage in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Malta. Cable coverage in large metropolitan areas in India is extensive. Cable plays a lesser role in the UK, a minor role in Japan and France [G20 countries], and none in Italy [a G20 country] and Greece, which is perhaps a part of why it is often overlooked. Public policy in many countries treats cable very differently from traditional telecommunications services, even though it is often used to provide services that function as a perfect substitute for traditional telecommunications. Where cable is present, it needs to be part of any regulatory analysis.

2.1.1 Promotion of competition

Competition can occur (1) within a technology, such as fixed telecommunications networks; (2) between two technologies that are somewhat substitutable for one another, such as fixed telecommunication networks and cable television networks, fixed wireless access, or satellite communications (e.g., geosynchronous GEO satellites or the newer low earth orbit (LEO) satellites). Similar considerations apply to mobile networks.

For the fixed network, it is not economically viable for two or more undertakings to lay wires or fiber to the same house in low-density areas of most countries. Some countries have both extensive fixed telecommunications and cable television infrastructure, but this is the exception rather than the rule. The “last mile” to the home constitutes a competitive bottleneck in most countries. Where it is impractical to introduce facilities-based competition, this is typically addressed by regulation that obliges the firm that controls the bottleneck last mile facility to make it available to competitors at cost-based prices (e.g., via unbundling). At a deeper level, regulated access to underground ducts and other passive infrastructure can play an important and positive role. Building wiring within multiple dwelling units can also represent a bottleneck facility amenable to regulatory measures. Approaches such as these are well developed in many countries, especially in Europe, but the requisite regulation is burdensome for the firms and may consequently slow broadband deployment. Constant attention is needed to tune regulation to balance these conflicting needs. (Visionary Analytics, Hocepied, & Marcus, 2021)

For mobile networks, policymakers generally seek to ensure enough network operators are present in the market. If entry by multiple mobile network operators (MNOs) is impractical, this need is sometimes addressed by introducing rules to enable mobile virtual network operators (MVNOs) to enter the market.

Recommendation 2. Implement procompetitive technology-neutral measures such as unbundling if and as appropriate but strike a balance with deployment incentives.

2.1.2 Novel ownership or operational models

Novel ownership or operational models sometimes seek to solve these competition problems differently. (Marcus, Porciuncula, Reisch, & Weber, 2021, pp. 19-22) Notable among these are (1) ownership and/or operation by the government; (2) structural or functional separation of the incumbent network operator; (3) co-investment models, primarily for the fixed network; and (4) mobile network infrastructure sharing.

Government ownership sometimes works well, notably in Sweden. Still, it can lead to economic distortions because the government’s incentives are inherently conflicted and because government investment risks crowding out private investment that might otherwise have eventuated; many of the protections that routinely apply to state aid are consequently relevant here.

Structural or functional separation seeks to solve the tension between competition and investment differently by removing the incentive of the firm with the last mile bottleneck facility to favor its own retail activities over those of competitors.

Co-investment is a newer approach that seeks to solve the same problem in yet another way by enabling all interested firms to invest in the bottleneck facility and control it jointly. Two of the most interesting examples of co-investment (although not treated as co-investment under the legal framework offered by EU regulation) are or were collaborations between an electric utility and a network operator in Ireland and Italy [a G20 country]. Infrastructure sharing (for instance, masts used by mobile base stations) represents another attempt to solve the tension between competition and investment in broadband deployment.

Many of these potential measures bring potential benefits but also reduce the effective number of fully independent competitors in a geographic region; consequently, regulatory authorities or competition authorities should carefully reflect on likely competitive effects before authorizing measures along these lines.

Recommendation 3. Be open to proposals from market players and municipalities to engage in creative ownership models such as municipal ownership, wholesale-only models, or infrastructure sharing and/or co-investment, but take due care not to unduly impede competition.

2.1.3 Reducing the cost of deployment

An alternative approach to driving down the cost of broadband deployment is by providing cost-effective access to scarce resources that are essential to its deployment. (Marcus, et al., 2017) For fixed networks, the cost of civil works (e.g., trenching) is often crucial. Access to land and rights of way can be critical; consequently, there can be merit in enabling broadband providers to use unrelated infrastructures (electric utility poles, sewers, water, and more) under fair terms and conditions.

Recommendation 4. Consider implementing measures to accelerate network infrastructure deployment by providing regulated, cost-oriented access to ducts, poles, and other civil engineering infrastructure used by other telecom operators or other utilities (e.g., electricity, water, sewers).

Simplifying and accelerating the granting of necessary municipal permits is a crucial, complex, but often overlooked element of this process. Permitting broadband providers to run aerial fiber could also be considered since it implies lower capital expenditure (CAPEX); however, the use of aerial fiber typically leads to higher operating costs (OPEX) due to its exposure to bad weather and other hazards.

Recommendation 5. Ensure that permitting processes are prompt, effective, and efficient.

In some countries, access to cable landing stations can also represent a significant impediment to the network deployment (researchICTafrica, 2016). Cable landing stations may constitute a different kind of bottleneck facility. Some countries impose high, non-cost-related charges to access and use cable landing stations. In others, network operators may impose high fees for high-capacity circuits or circuit equivalents to reach the cable landing station, thus imposing a particular burden on low-income land-locked countries. Given the enormous societal value of having and using modern telecommunications, governments should refrain from imposing (excessive) taxes on cable landing stations and prevent network operators from setting excessive, non-cost-related charges on circuits and equivalents used to access cable landing stations.

Recommendation 6. Avoid placing needless taxes or other burdens (or imposing unnecessary expense) on access to landing stations for submarine cables.

2.1.4 Enabling mobile network deployment

Additional factors apply to the deployment of mobile broadband. First and foremost, national regulatory bodies should assign suitable radio spectrum for mobile broadband in a fair, efficient, and timely fashion. Delay in spectrum assignment can represent a substantial negative impact on societal welfare. (Hazlett & E.Muñoz, 2009); (Marcus, et al., 2017, pp. 364-366)

Recommendation 7. Ensure that radio spectrum assignments for mobile services are conducted promptly, effectively, efficiently, and fairly.

It is likewise important that policymakers resist the temptation to artificially jack up the auction price of the spectrum as a form of taxation. Doing so tends to slow deployment and raise mobile broadband prices, impacting consumer welfare. (Marcus, et al., 2017, pp. 367-368) The goal of spectrum auctions is to ensure allocative efficiency—the revenue raised by the government is a convenient by-product (Coase, 1959) but should not be exploited to the detriment of societal welfare.

Recommendation 8. Avoid the temptation to use the spectrum assignment process to maximize government revenue.

Mobile broadband deployment, especially with the expected movement to small cells in densely settled areas under 5G, heavily depends on the same permitting and right-of-way access considerations already identified for fixed networks. Overcoming public resistance, to the extent that it is not objectively justified, is particularly important. “Not in my back yard (NIMBY)” considerations that delayed deployment of large cellular masts in the past are far less relevant for tiny microcells that are barely visible on street furniture (e.g., at bus stops) or on the side of buildings.

Recommendation 9. Consider simplified permitting processes for small mobile base stations (e.g., for 5G in dense metropolitan regions).

As regards public concerns over possible health effects of mobile services (EMF), there are no demonstrated harms (and no particular reason to expect more problems on balance with 5G services than with previous generations); however, the evidence is not 100% conclusive, and perhaps will never be entirely conclusive. If harms were common, they likely would have been obvious long ago in epidemiological cohort studies. Policymakers should not overreact to public fears that are not based on objective science. (Pujol, et al., 2019, pp. 103-123) (Marcus, Porciuncula, Reisch, & Weber, 2021, p. 27)

Recommendation 10. Measures to deal with possible health effects of mobile services should not go substantially beyond what is called for based on well-founded scientific and medical advice.

2.2 Demand-side measures

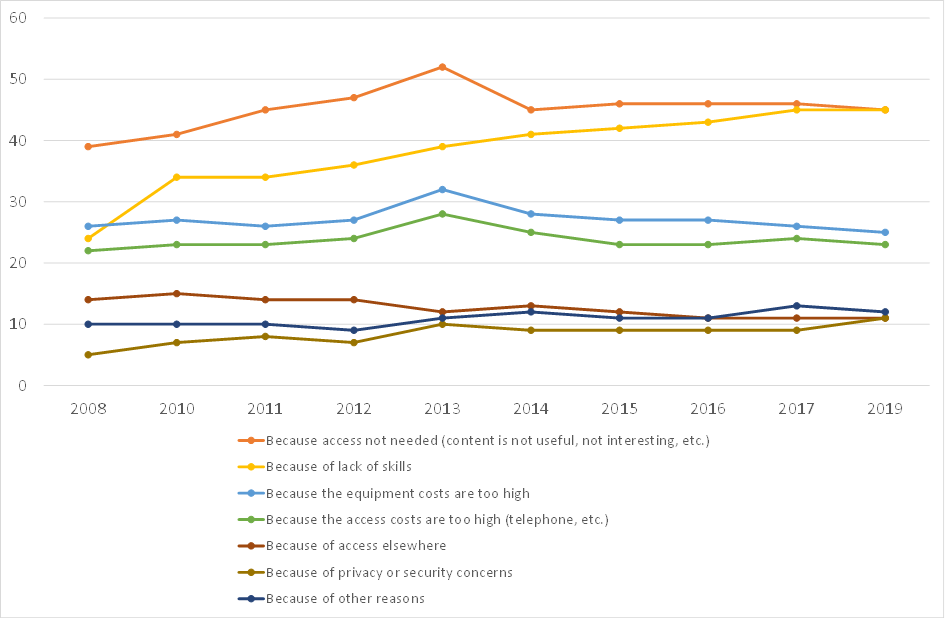

In many countries, the greatest challenge in achieving broadband adoption and usage (as distinct from deployment) is neither with the availability or the service nor with its cost, but rather with lack of training or interest on the part of consumers. This is well documented for the EU (see Figure 3) and the United States. (Marcus, Porciuncula, Reisch, & Weber, 2021, p. 57) Particularly striking is (1) the increase over time in the importance of lack of training and, to a lesser degree, (2) the increase in the relative importance of the sense that access is not needed (because the content is not helpful or not interesting, for example), together with (3) growing concerns over privacy and security.

Shortfalls in training and consumer interest cannot be solved solely by “pushing” with supply but must also be “pulled” using demand side measures.

Figure 3. Reasons for not having Internet access at home, European Union (April 2017).

Source: Based on data from Eurostat (2018), “Reasons for not having Internet access at home,” https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tin00026/default/table?lang=en.

Once broadband service is sufficiently widely available, demand-side measures can be considerably more effective than supply-side measures in promoting take-up. (Belloc, Nicita, & Rossi, 2011) (Parcu, 2011) (Marcus, et al., 2013) The measures considered in (Parcu, 2011) were (1) demand aggregation policies; (2) direct demand subsidies (discounts on the purchase of equipment or broadband services, direct subsidies, or tax breaks); (3) coordinating government demand (through procurement policy or by promoting e-government services); (4) incentives to private demand for the poor and the elderly; and (5) incentives to business demand.

Recommendation 11. Consider implementing direct demand subsidies (discounts on purchasing equipment or broadband services, direct subsidies, or tax breaks) as appropriate, together with incentives to private demand for the poor, the elderly, and other disadvantaged groups. Doing so serves both to promote broadband adoption and to reduce “digital divides.”

Recommendation 12. Consider implementing demand-side measures such as aggregation of demand, procurement policies that foster broadband adoption, or promotion of e-government services.

The survey data depicted in Figure 3 also suggest a need (at least in Europe, but presumably in many other countries as well) for better and more internet-specific education and training and for steady improvements in the cybersecurity and privacy offered by online services.

Training has a significant role to play here. The COVID-19 pandemic has driven a dramatic acceleration of the tendency for knowledge workers to work from home. This has implied the need for many workers to familiarise themselves not only with traditional internet skills but also with videoconferencing tools such as Zoom and Microsoft Teams. (Marcus, Petropoulos, & Aloisi, 2022) The ability to shop online has likewise taken on far greater importance than in pre-pandemic days.

Increasing digitalization, and especially the increasing use of artificial intelligence and machine learning, are transforming the workplace in most countries in profound ways. The current view of most experts is that earlier fears that vast numbers of jobs would suddenly disappear were overblown; however, it is clear that a great many jobs will be radically transformed in the next decade or two. This is yet another factor that suggests the need not only for more education and training but also for a different kind of education and training. It is no longer appropriate to think of education solely as something one undertakes before one begins a career; instead, a shift to lifelong learning is urgently needed but has been slow in coming because it confronts so many institutional rigidities in most countries. (Petropoulos, Marcus, Moës, & Bergamini, 2019)

Recommendation 13. Education and training focusing on digital skills are fundamental to the modernization of society, adaptation to the changing workplace, and the avoidance of digital divides. There is an urgent need to move beyond traditional models of education and training and instead toward a focus on lifelong learning.

There is also good reason to think that lack of trust in the internet can serve to depress adoption and usage (see for instance Figure 3); consequently, measures to strengthen cybersecurity, robustness, and privacy for services on the internet can all contribute, in addition to the promotion of greater adoption and use of broadband internet access (even if quantitative substantiation of this linkage is limited).

Recommendation 14. Ensuring that broadband internet services are secure, reliable, robust, and respectful of personal privacy helps promote the take-up and use of these services.

2.3 Financing deployment of broadband infrastructure

In this section, we consider investment needs for fixed and mobile broadband (Section 2.3.1); the implications of a de-globalizing world (Section 2.3.2); promotion of private investment (Section 2.3.3); and means of public investment, including some new options that pandemic recovery and revision of global tax rules have opened up (Section 2.3.4).

2.3.1 Investment needs

It is perhaps helpful to begin with, an order of magnitude estimate of investment needs. These costs are strongly influenced by the quality of service (QoS) that the network is expected to deliver; the degree of coverage desired (coverage of a small percentage of the national territory that is hard to reach with less capable broadband can result in significant savings); and by numerous modeling assumptions. A few countries already have (or are well on their way to having) full coverage of highly capable broadband across much or all of the national territory. Japan, the Republic of Korea, [both are G20 countries], and the Netherlands are good examples. For most others, significant further investment will be needed.

If we take the European Union as a benchmark, the European Investment Bank (EIB) has estimated (European Investment Bank, 2018) the magnitude of the funding gap to achieve the European Union’s fixed and mobile broadband objectives, as expressed in the Digital Agenda for Europe (DAE) (European Commission, 2010) together with the European Gigabit Strategy (EGS). (European Commission, 2016) The EGS establishes strategic objectives by 2020 of (i) achieving availability of 5G connectivity as a fully-fledged commercial service in at least one major city in each Member State; and by 2025 of achieving (ii) “Gigabit connectivity for all main socio-economic drivers such as schools, transport hubs and main providers of public services as well as digitally intensive enterprises;” (iii) uninterrupted 5G coverage for all urban areas and all major terrestrial transport paths; and (iv) providing access to Internet connectivity offering a downlink of at least 100 Mbps, upgradable to Gigabit speed, to all households in the European Union, rural or urban. The EIB found that a total investment of USD 453 billion would be required by 2025 under the most likely assumptions. The EIB further estimated that USD 153 billion (33%) of that funding could be expected to come from private investments and that the remaining USD 300 billion represented an investment gap that would somehow have to be addressed by some combination of public policy interventions. (Marcus, Porciuncula, Reisch, & Weber, 2021)

There are a number of caveats that must be considered regarding these numbers. First, they reflect the state of play as of 2018, not the current state of play, and indeed not the impact of the pandemic. Second, and relatedly, investments subsequently made with EU, member state, regional or local funds are not reflected. Third, the most recent set of EU goals, as expressed in the Digital Compass (European Commission, 2021) that all “households … be covered by a Gigabit network, with all populated areas covered by 5G” are not reflected in these estimates.

For the United States, the US FCC’s Paul de Sa estimated the cost of rolling out service at 25 Mbps download speed and 3 Mbps upload speed to approximately 14% of the 160 million US residential and small-and-medium business locations that did not already have correspondingly fast fiber-to-the-premise (FTTP) or cable service would be about USD 80 billion[3] for full coverage, but only about USD 40 billion to achieve 98% coverage (once again because the cost per household for the last 2% of locations is very high). (de Sa, 2016)

A clear implication of this analysis (together with similar results for other countries) is that in many countries, achieving good coverage to the most remote or hardest-to-reach 1% or 2% of the population can be associated with very high unit costs. Alternative deployment technologies (fixed wireless access, mobile, or satellite) should be considered.

2.3.2 A world order that has changed poses impediments to deployment

Before discussing the possibilities of funding the global transition to modern broadband based on fixed fiber assets and 5G mobile networks, it is necessary to say a few words about how the international world order has changed and the implications for broadband deployment and adoption.

From 1945 to 2022, the world enjoyed a period of relative tranquillity in which confidence in global value chains (GVCs) was high. With the return of kinetic warfare to Europe in 2022 and with growing US-China rivalry, this is no longer a given. As regards Russia, high-tech decoupling is already a well-advanced (Marcus, Poitiers, & Weil, 2022), (Grzegorczyk, Marcus, Poitiers, & Weil, 2022).

It is important, however, to bear in mind that global value chains were disrupted long before Russia invaded Ukraine. The pandemic had already led to significant disruption due to shortages of shipping containers and labor shortages. Trade tensions between China and the United States might have been simmering before 2017, but they exploded with the election of Donald Trump. Trade tensions also escalated between the United States and the European Union during the Trump years.

Trade restrictions for both fixed and mobile technologies are likely to pose a growing threat to broadband deployment. They will often imply that it is impractical to purchase equipment and services from the best price/performance vendor. They raise deployment costs.

A further related question is whether we will end up with a fully interoperable global communications system. Standards for 4G and 5G converged to enable full global interoperability, but this was not always the case in the past. Standards for 2G were hugely fragmented between the EU, Japan, and the USA (and were even fragmented within the USA). This fragmentation persisted with 3G.

Current standards activities for 6G, the next generation of mobile services (expected to begin deployment circa 2030), seem to be on track to produce fully interoperable standards, at least at the airlink level. Whether this apparent unity can be maintained in the face of massive and growing geopolitical stresses remains to be seen. If interoperability cannot be maintained, it might no longer be possible to use the same mobile phone or tablet when traveling from one country to another, similar to the fragmentation experienced under 2G and 3G mobile services.

Concerns in the United States have mainly centered on the concern that China would exert undue influence over the standards development process; however, this does not appear to be the case. (Bruer & Brake, 2021) have found that “participation by Chinese actors is certainly increasing, but the outcomes of the process generally appear to be fair, with notable exceptions being relatively rare.” In the same vein, (Neaher, Bray, Mueller-Kaler, & Schatz, 2021) finds that “Chinese representation within standards bodies is far from reaching a disproportionate level, especially in comparison to the country’s economic weight.”

Increasing reliance on a wide range of de facto trade sanctions (Gibson Dunn, 2021), (US Department of the Treasury, 2021), on the other hand, has already resulted in a significant degree of decoupling—not only classic restrictions on exports and imports, but also secondary sanctions, restrictions on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), and restrictions on visas for experts from other countries.

Trade restrictions can be associated with significant costs. Among the potential costs are (1) the aforementioned loss of interoperability; (2) relatedly, the loss of the ability to seamlessly roam; (3) loss of manufacturing economies of scale; (4) unrealized gains in trade where components could have been manufactured more efficiently in one country than in another; and (5) less robust competition for electronic communications equipment and services, resulting in higher end-user prices and less choice.

Recommendation 15. Trade restrictions can sometimes be appropriate and may be unavoidable in a world subject to increasing geopolitical stress; be sensitive, however, to the economic, operational, social, and practical costs (on your country and other countries) associated with any restrictions that you impose.

2.3.3 Private investment

The promotion of domestic private investment is desirable, but it is mainly up to domestic investors, not to policymakers. The primary role of policymakers is to ensure that public policy interventions do not become so intrusive as to depress private investment.

For foreign investment, the increasingly polarised world poses real challenges. Generally, we tend to support Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Telecommunications, however, has always been a special case—a country’s core telecommunications network has traditionally been viewed as a strategic asset. Plans of foreign entities to invest in these networks have often led to intensive reviews by national security authorities (with noteworthy examples, for instance, in the United States, and in Italy).

In an era of increasing political tension, especially between the USA and China, a careful review of any significant proposed foreign investments in critical communications network firms or other key digital infrastructure will unavoidably require intensive, careful review by national authorities. How durable is the friendly, peaceful relationship with the country of the firm that wishes to invest? If there is a significant risk of future conflict with the investor’s country (or perhaps with the government of a firm that might acquire the firm that wishes to invest), the investment may be ill-advised. No country will want to be vulnerable to foreign pressure over such a critical asset or possibly to be subject to clandestine surveillance from its telecommunications network.

Recommendation 16. Avoid needless restrictions on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in electronic communications networks. At the same time, in light of the criticality of electronic communications and the increasingly tense world we live in, the risk of possible future conflict or stress with the country concerned must be carefully weighed before permitting FDI into core electronic communications assets.

For similar reasons, the choice of equipment and software for key telecommunications assets has become much more delicate. If a dispute should arise with another country, no country will want to be vulnerable to covert foreign surveillance within its core telecommunications networks. An unfortunate corollary of these considerations is that the cost of building and operating broadband networks is likely to increase due to geopolitical tensions since it may no longer be appropriate to purchase gear from the supplier with the most cost-effective gear.

Recommendation 17. In light of an increasingly tense world, it has now become necessary to weigh the risk of possible future conflict or stress carefully with the supplier country when selecting equipment that will play a key role in core telecommunication networks.

2.3.4 Targeted public subsidy

When it comes to broadband internet access, there are two main rationales and forms of public subsidy: (1) subsidies to individuals to make the service affordable for individuals who are poor, disabled, or otherwise disadvantaged; and (2) targeted subsidies to network operators so as compensate for the difference between what consumers are willing to pay, and the short-run marginal cost of the services (below which the service cannot be profitable).

Affordability subsidies are an important means of mitigating digital divides within a country. These subsidies have already been covered in Section 2.2. The goal is to ensure that anyone who wants broadband internet access can afford it, but typically not oblige people to actually subscribe. The mechanisms used to manage these subsidies and to fund them can be very diverse from one country to the next. In some countries, they are treated as an element of social protection, while in others, they are administered under telecommunications regulation as an element of universal service.

Recommendation 18. Most countries require some degree of public subsidy for broadband, either to ensure that broadband is affordable for all consumers or to ensure that it reaches all (inhabited) parts of the national territory.

The targeted aid to network operators is a public subsidy that raises many familiar state aid concerns. First, a public subsidy can crowd out private investment that otherwise might have been expected; consequently, it is important to fund deployment only in regions that otherwise would not have experienced significant broadband deployment for quite some time. Second, the subsidies can easily lead to economic distortions; consequently, it is important to implement the support in such a way as to avoid needless distortion. This implies the need for rules that typically require periodic review and refinement. (European Commission, 2021)

Recommendation 19. When public subsidy is provided for broadband, typical state aid concerns must be reflected. Aid should not be provided for areas that could be funded by private investment. Economic distortions should be avoided as much as possible.

So much for mechanism. A possibly more immediate question is, what is the most appropriate source of the funds, particularly considering that they are likely to be substantial?

Some countries have already achieved substantially complete fixed and mobile broadband network deployment, while others have plans and can generate sufficient funds through available domestic revenues. Our focus in the following sections is on possible tools for countries that struggle to finance the broadband deployment that is fundamental to their digital transformation.

Judicious use of pandemic recovery funds

Many countries are implementing substantial and generous programs of grants and loans to finance recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. It is widely recognized that these funds should not be used solely to rebuild what was there before, with the inefficiencies and problems already embedded in the old infrastructure, but rather to modernize society as a whole. It can therefore be appropriate to tap recovery funds to promote digitalization, including broadband deployment. The United States and the European Union represent instructive case studies of how this has already been implemented.

In the United States, these considerations are directly reflected in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. The primary tool is current USD 42.45 billion in funding for broadband deployment grants delegated to the states for roughly the period 2022-2026. As a prelude to the use of these grants, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act obliges the US FCC to prepare new DATA maps of broadband deployment, and strengthens the empowerment of the FCC to do so. The DATA maps are to identify unserved and underserved areas, where an unserved area either is an area that either “has no access to broadband service” or else “lacks access to reliable broadband service offered with a speed of not less than 25 megabits per second for downloads; and 3 megabits per second for uploads; and a latency sufficient to support real-time interactive applications.”. The definition of an underserved area is nearly the same, but with 100 Mbps download and 20 Mbps upload speed.

In the European Union, digitalization is one of the main priorities of the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), the largest component of Next Generation EU (NGEU), the European Union’s landmark instrument for recovery from the coronavirus pandemic. The RRF made EUR 338 billion in grants available and EUR 385.8 billion (in 2018 EUR) in loans on favorable terms; however, very little use has been made to date of the loans. EU countries were to spend at least 20% of the funds available from the RRF on digitalization or dealing with its impacts over six years from 2021 to 2026, and 37% on sustainability. National implementation plans for the grants call for 26% of these expenditures to be used for digitalization and 40% for sustainability, thus exceeding the RRF requirements. (European Commission, 2021) Broadband featured prominently in the goals of the RRF, but only 9% (EUR 10.7 billion) of funds requested under the grant facility are, in fact, being spent on connectivity. (Darvas, Marcus, & Tzaras, 2021) There would thus be an opportunity to do more.

Recommendation 20. Many countries are providing public funding to help recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. The same funds should at the same time be spent in such a way as to modernize society. Public subsidy of broadband can thus be an appropriate use of pandemic recovery funds.

Possible relevance of new corporate taxation funds

There has been a growing chorus of voices, mainly in Europe, calling for the largest online platform providers, based mainly in the USA and China, to make additional contributions to fund the deployment and operation of broadband networks. An open letter from the CEOs of 13 major European network operator firms called for a “… renewed effort to rebalance the relationship between global technology giants and the European digital ecosystem. … Large and increasing part of network traffic is generated and monetized by big tech platforms, but it requires continuous, intensive network investment and planning by the telecommunications sector. This model—which enables EU citizens to enjoy the fruits of the digital transformation—can only be sustainable if such big tech platforms also contribute fairly to network costs.” (European Telecommunications Network Operators’ Association, 2021)

One can debate the claim, but the claim seems to ignore the fact that the very same firms are expected to begin soon to make large new corporate tax payments to European governments.

The OECD has been working for many years to achieve consensus on corporate taxation for multinational enterprises (MNEs) through its Base Erosion and Profit Sharing (BEPS) project. It had long been recognized that current rules make it easy for firms, especially high tech firms, a large portion of whose value consists of intangible assets, to structure their tax reporting to park the bulk of the assets in jurisdictions where tax rates were low or zero. The BEPS reforms were introduced because changes associated with digitalization and globalization “have brought with them challenges to the rules for taxing international business income, which have prevailed for more than a hundred years and resulted in MNEs not paying their fair share of tax despite the huge profits many of these businesses have garnered as the world has become increasingly interconnected.” (OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, 2021) The lion’s share of the new, increased tax revenues is expected to come from firms associated with online digital services and e-commerce, many of which are based in the United States, and some in China. These firms benefit from a global market that is well-served by fast and reliable broadband access.

The rules that were internationally agreed upon late in 2021 by the OECD and G20, some 140 countries in all, have the effect of (1) redistributing corporate tax revenues such that corporate tax is collected in the country in which profits are earned (referred to as Pillar One), and (2) setting a minimum corporate tax rate of 15% (Pillar Two). (OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, 2021) The minimum corporate tax rate of 15% can be expected to reduce the incentive for technology firms, including the largest digital platforms, to park assets in low tax jurisdictions.

These funds are general taxation revenue—they are not linked to broadband deployment. It is up to national governments to determine how they will be used. But they will, for the most part, be paid by the same firms that allegedly do not contribute their “Fair Share” to broadband deployment worldwide, and it is clear that they are large enough to potentially serve, if desired, as an important spur to broadband deployment.

As far as the magnitude of the payments, the OECD has estimated the global impact on national corporate tax revenues to be substantial: “Under Pillar One, taxing rights on more than USD 125 billion of profit are expected to be reallocated to market jurisdictions each year. With respect to Pillar Two, the global minimum tax rate of 15% is estimated to generate around USD 150 billion in new tax revenues globally per year.” (OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, 2021)

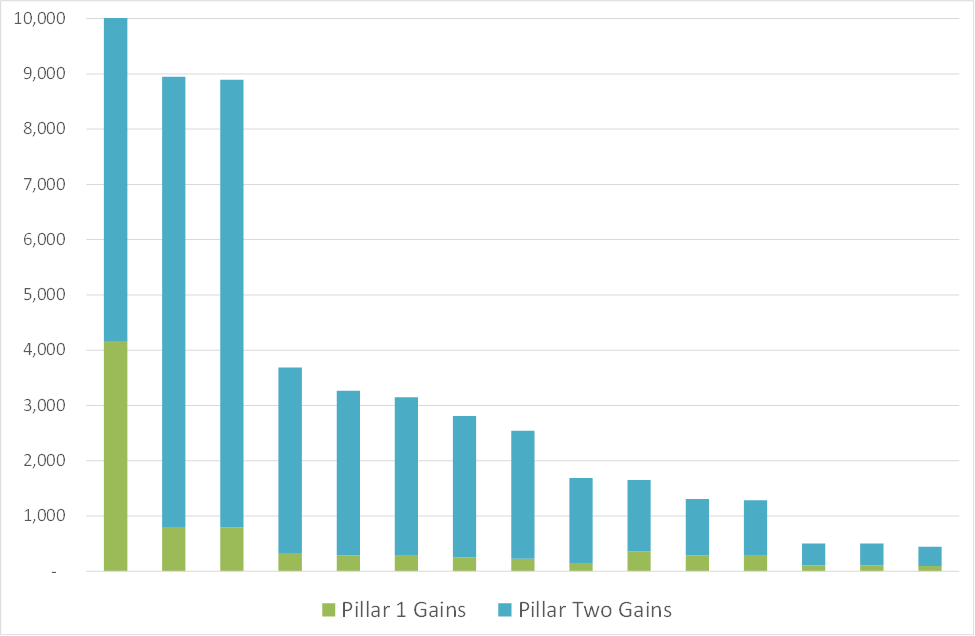

The same OECD Impact Assessment report (OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, 2021) included a country-by-country estimate of expected gains in corporate tax revenues. Unfortunately, this analysis is not public; however, it is possible to make some rough extrapolations from the published report (see Figure 4).

The gains from the BEPS corporate tax reforms are not limited to developed economies. Among developed G20 economies, the US, Japan, Australia, Great Britain, South Korea, and Canada are big winners based on our conservative estimate of annual gains in corporate tax revenue; however, China is by far the largest overall. The gains of Brazil and Mexico are comparable to those of countries like Spain.

Figure 4. Gains in annual corporate tax revenue (million USD per year) for selected G20 countries.

Source: Bruegel calculations based on OECD corporate tax statistics and (OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, 2020). Note that the total value for China is USD 19.2 billion.

Recommendation 21. Consider taking advantage (in one way or another) of a portion of the new corporate taxation revenues you will receive due to the new OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) reforms to subsidize broadband deployment and adoption.

Loans from international Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and other sources

For many countries, the most cost-effective means of financing broadband development will be using a loan from one of the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) such as the World Bank, the European Investment Bank (EIB), or the Asian Development Bank (ADB). Because an MDB loan spreads risk, interest rates are generally favorable compared to those that a developing country could obtain on its own.

Within the EU, for instance, the previously mentioned RRF may represent a particularly attractive means of financing for some of the EU Member States. As previously noted, the Member States of the EU have already applied for all of the grant money; however, less than half of the EUR 385.8 billion available under the RRF loan facility has been touched so far—only EUR 166.0 billion, three quarters of which was requested by Italy. (Darvas, et al.) It is possible under the RRF Regulation to apply for an RRF loan until August 2023. This is a large sum of money relative to EU broadband investment needs. But it will not be attractive to every EU Member State—Germany, for example, can probably obtain more favorable terms on its own.

Recommendation 22. Consider using a loan to accelerate the availability of funds for public subsidies for broadband deployment. This might be provided by (for instance) one of the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), or might be obtained by tapping pandemic recovery funds where appropriate.

CONCLUSION

Broadband needs have become even more critical in light of recent shocks to the global economy, including the global COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Together with US-China strategic competition, these strains risk technological and market decoupling that complicates achieving global broadband deployment and adoption.

This complicated scenario calls for supply and demand side measures to ensure that broadband is deployed, adopted, and used.

The key recommendations to policymakers in this proposal are:

- Supply-side: Boost deployment of broadband infrastructure and services by making prerequisites available and driving down the cost to providers.

- Procompetitive tools

- Prompt and efficient access to spectrum and to land and rights of way

- Sharing of (passive) infrastructure, including suitable non telecommunications infrastructure

- Demand side: Boost adoption and use of broadband services by ensuring that internet is available, affordable, and usable.

- Direct subsidy

- Demand aggregation

- Education and training

- Privacy and security

Funding: Pursue new, innovative sources of finance to support public funding to selectively accelerate deployment where needed.

References

Belloc, F., Nicita, A., & Rossi, M. (2011). The Nature, Timing and Impact of Broadband Policies: a Panel Analysis of 30 OECD Countries. University of Siena.

Benedek, W., Bílková, V., & Sassòli, M. (2022). Report on Violations of International Humanitarian and Human Rights Law, War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity Committed in Ukraine since 24 February 2022. Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe: Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights.

Bruer, A., & Brake, D. (2021). Mapping the International 5G Standards Landscape and How It Impacts U.S. Strategy and Policy. ITIF.

Campbell, S., Castro, J. R., & Wessel, D. (2021). The benefits and costs of broadband expansion. Brookings. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2021/08/18/the-benefits-and-costs-of-broadband-expansion/

Coase, R. (1959). The Federal Communications Commission. University of Chicago Press.

Czernich, N., Falck, O., Kretschmer, T., & Woessmann, L. (2011). Broadband Infrastructure and Economic Growth. The Economic Journal, 121(552), 505-532. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2011.02420.x

Darvas, Z., Domínguez-Jiménez, M., Devins, A. I., Grzegorczyk, M., Guetta-Jeanrenaud, L., Hendry, S., . . . Weil, P. (n.d.). European Union countries’ recovery and resilience plans. Bruegel. Retrieved from https://www.bruegel.org/publications/datasets/european-union-countries-recovery-and-resilience-plans/

Darvas, Z., Marcus, J. S., & Tzaras, a. A. (2021). Will European Union recovery spending be enough to fill digital investment gaps? Retrieved from https://www.bruegel.org/2021/07/will-european-union-recovery-spending-be-enough-to-fill-digital-investment-gaps/

de Sa, P. (2016). Improving the Nation’s Digital Infrastructure. FCC Office of Strategic Planning.

European Commission. (2010). A Digital Agenda for Europe.

European Commission. (2016). Connectivity for a Competitive Digital Single Market – Towards a European Gigabit Society.

European Commission. (2021). 2030 Digital Compass: the European way for the Digital Decade.

European Commission. (2021). Recovery and Resilience Facility. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/recovery-coronavirus/recovery-and-resilience-facility_en#:~:text=It%20makes%20available%20%E2%82%AC723.8,spurring%20growth%20in%20the%20process.

European Commission. (2021). State Aid: Commission invites comments on proposed revision of EU State aid rules for deployment of broadband networks. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_6049

European Investment Bank. (2018). A study on the deployment costs of the EU strategy on Connectivity for a European Gigabit Society.

European Telecommunications Network Operators’ Association. (2021). Joint CEO Statement: Europe needs to translate its digital ambitions into concrete actions. Retrieved from https://etno.eu/news/all-news/717-ceo-statement-2021.html

Fanfalone, A. G. (2022). Emerging Trends in Communication Market Competition. OECD.

FCC. (2010a). Connecting America: The National Broadband Plan. Federal Communication Commission. Retrieved from https://transition.fcc.gov/national-broadband-plan/national-broadband-plan.pdf

FCC. (2010b). The Broadband Availability Gap.

Fukuyama, F. (1992, 2006). The End of history and the last man. Free Press.

Gibson Dunn. (2021). 2021 Year-end Sanctions and Export Controls Update.

Grzegorczyk, M., Marcus, J. S., Poitiers, N. F., & Weil, P. (2022). The decoupling of Russia: high-tech goods and components. Bruegel. Retrieved from https://www.bruegel.org/2022/03/the-decoupling-of-russia-high-tech-goods-and-components/

Hazlett, T. W., & E.Muñoz, R. (2009). A welfare analysis of spectrum allocation policies. RAND Journal of Economics 40(3), 424-454.

International Telecommunications Union (ITU). (2021). Regional global key ICT indicator aggregates. Retrieved April 10, 2022, from https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/facts/ITU_regional_global_Key_ICT_indicator_aggregates_Oct_2021.xlsx

Marcus, J. S., Godlovitch, I., Nooren, P., Eilxmann, D., Ende, B. v., & Cave, J. (2013). Entertainment x.0 to boost Broadband Deployment. Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/document/activities/cont/201310/20131017ATT72946/20131017ATT72946EN.pdf

Marcus, J. S., Poitiers, N. F., & Weil, P. (2022). Bruegel. Retrieved from https://www.bruegel.org/2022/03/the-decoupling-of-russia-software-media-and-online-services/

Marcus, J. S., Porciuncula, L., Reisch, M., & Weber, V. (2021). Broadband Technology and Policy Developments. OECD Digital Economy Papers number 317, OECD. Retrieved from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/oecd-digital-economy-papers_20716826

Marcus, J. S., Stumpf, U., Kroon, P., Lucidi, S., Nett, L., Bocarova, V., . . . Queck, R. (2017). Substantive issues for review in the areas of market entry, management of scarce resources and general end-user issues. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/substantive-issues-review-areas-market-entry-management-scarce-resources-and-general-end-user-0

Marcus, J., Petropoulos, G., & Aloisi, A. (2022, February 4). COVID-19 and the accelerated shift to technology-enabled Work from Home (WFH). Retrieved from https://www.bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/COVID-19-technology-and-WFH.pdf

Neaher, G., Bray, D. A., Mueller-Kaler, J., & Schatz, B. (2021). Standardizing the Future: How Can the United States Navigate the Geopolitics of International Technology Standards?

OECD. (2011). OECD Principles for Internet Policy Making. OECD Publishing, Paris. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/internet/ieconomy/oecd-principles-for-internet-policy-making.pdf

OECD. (2012). Recommendation of the Council on Broadband Connectivity.

OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project. (2020). Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Economic Impact Assessment. doi:https://doi.org/10.1787/0e3cc2d4-en

OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project. (2021). Statement on a Two-Pillar Solution to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy .

OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project. (2021). Two-Pillar Solution to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy.

Parcu, P.-L. (2011). Study on Broadband Diffusion: Drivers and Policies: Study for the Independent Regulators Group. Florence School of Regulation.

Petropoulos, G., Marcus, J. S., Moës, N., & Bergamini, E. (2019). Digitalisation and European welfare states. Bruegel. Retrieved from https://bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Bruegel_Blueprint_30_ONLINE.pdf

Pujol, F., Manero, C., Ropert, S., Enjalbal, A., Lavender, T., Jervis, V., . . . Marcus, J. S. (2019). Study on using millimetre waves bands for the deployment of the 5G ecosystem in the Union.

researchICTafrica. (2016). Towards a definition of Open Access. Property of Communications Regulators Association of Southern Africa (CRASA).

Röller, L.-H., & Waverman, L. (2001). Telecommunications Infrastructure and Economic Development: A Simultaneous Approach. American Economic Review, 91(4), 909-923. doi:10.1257/aer.91.4.909

US Department of the Treasury. (2021). The Treasury 2021 Sanctions Review.

Visionary Analytics, Hocepied, C., & Marcus, J. S. (2021). Study on Regulatory Incentives for the Deployment of Very High Capacity Networks in the Context of the Revision of the Commission’s Access Recommendations. Retrieved from https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/study-regulatory-incentives-deploying-very-high-capacity-networks-commissions-accessAppendix

The detailed recommendations to policymakers, as they appear in the text, are collected here.

Recommendation 5. Ensure that permitting processes are prompt, effective, and efficient.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

| J Scott Marcus, Bruegel

J. Scott Marcus is a Senior Fellow at Bruegel, a Brussels-based economics think tank, and also works as an independent consultant dealing with policy and regulatory policy regarding electronic communications. His work is interdisciplinary and entails economics, political science / public administration, policy analysis, and engineering. From 2005 to 2015, he served as a Director for WIK-Consult GmbH (the consulting arm of the WIK, a German research institute in regulatory economics for network industries). From 2001 to 2005, he served as Senior Advisor for Internet Technology for the United States Federal Communications Commission (FCC), as a peer to the Chief Economist and Chief Technologist. In 2004, the FCC seconded Mr. Marcus to the European Commission (to what was then DG INFSO) under a grant from the German Marshall Fund of the United States. Prior to working for the FCC, he was the Chief Technology Officer (CTO) of Genuity, Inc. (GTE Internetworking), one of the world’s largest backbone internet service providers. Mr. Marcus is a member of the Scientific Committee of the Communications and Media program at the Florence School of Regulation (FSR), a unit of the European University Institute (EUI). He is also a Fellow of GLOCOM (the Center for Global Communications, a research institute of the International University of Japan). He is a Senior Member of the IEEE; has served as co-editor for public policy and regulation for IEEE Communications Magazine; served on the Meetings and Conference Board of the IEEE Communications Society from 2001 through 2005; and was Vice Chair and then Acting Chair of IEEE CNOM. He served on the board of the American Registry of Internet Numbers (ARIN) from 2000 to 2002. Marcus holds a B.A. in Political Science (Public Administration) from the City College of New York (CCNY), and an M.S. from the School of Engineering, Columbia University. Alicia Garcia Herrero (Bruegel)

Alicia García Herrero is a Senior Fellow at European think-tank BRUEGEL. She is also the Chief Economist for Asia Pacific at Natixis, and a non-resident Senior Follow at the East Asian Institute (EAI) of the National University Singapore (NUS). Alicia is also Adjunct Professor at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Finally, she is a Member of the Council of Advisors on Economic Affairs to the Spanish Government and an advisor to the Hong Kong Monetary Authority’s research arm (HKIMR) among other advisory and academic positions. In previous years, Alicia held the following positions: Chief Economist for Emerging Markets at Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria (BBVA), Member of the Asian Research Program at the Bank of International Settlements (BIS), Head of the International Economy Division of the Bank of Spain, Member of the Counsel to the Executive Board of the European Central Bank, Head of Emerging Economies at the Research Department at Banco Santander, and Economist at the International Monetary Fund. Alicia has maintained a part-time academic life throughout her career as Visiting Professor at John Hopkins University (SAIS program), at the China Europe International Business School (CEIBS) in Shanghai, Carlos III University in Madrid among others. Alicia holds a PhD in Economics from George Washington University and has published extensively in refereed journals and books (her publications can be found in ResearchGate, Google Scholar, SSRN or REPEC). Alicia is also very active in international media (Bloomberg and CNBC among others) as well as social media (Twitter and LinkedIn). Alicia was included in the TOP Voices in Economy and Finance by LinkedIn in 2017 and #6 Top Social Media leader by Refinitiv in 2020. |

| Lionel Guetta-Jeanrenaud (Bruegel)

Lionel is working at Bruegel as a Research Assistant. He studied economics at the Ecole normale supérieure de Lyon, in France. Before joining Bruegel, Lionel worked as a research assistant at the Department of Economics of Harvard University. His Master’s thesis investigated the impact of newspaper closures on anti-government sentiment in the United States. In addition to media economics and political economy, his research interests include fiscal policy and the digital economy. |

- Adoption is typically measured per 100 inhabitants in order to avoid the question of how to define a household or a family. For mobile adoption, a subscription generally serves a single individual, so this works well enough; for fixed subscriptions, however, a subscription typically serves an entire family. ↑

- These data need to be interpreted with caution. Some individuals have more than one mobile subscription, and this does not always reflect a consumer benefit. In some countries, defects in regulation (call termination, roaming) lead some consumers to keep a separate mobile phone for each network with which they make frequent contact. ↑

- In then-current US dollars. ↑