Challenge

Proposal

The G20 annually brings together the leaders of the world’s largest energy producers, consumers and polluters. Responsible for 77% of global energy consumption and 82% of all global carbon dioxide emissions, G20 members also contain more than 80% of the world’s installed renewable capacity and provide 90% of aid in the global energy sector. This makes the G20 an ideal steering committee for global energy governance, by channelling dialogue and driving international action on global energy policy.

But some see G20 members’ divergent perspectives on energy policy as an insurmountable challenge to collective action. Indeed, although some countries’ domestic energy policies are market driven, others, including Saudi Arabia, rely on state ownership to secure their energy supply, and still others, including China, rely on state intervention. But the G20’s informal format provides a unique opportunity for these global energy leaders to meet on an equal footing and share their national views. As a result, this relatively small yet highly influential group of dominant energy players plays a pivotal role.

Conclusions

The G20 first mentioned energy at its 2008 Washington Summit, but it was only at the 2011 Cannes Summit that climate and energy were directly linked, in a section of the declaration on “improved energy efficiency and better access to clean technologies” for “sustainable and inclusive” growth. At St Petersburg in 2013, G20 leaders dedicated 7% of their declaration to energy policy.

At their 2014 Brisbane Summit, G20 leaders considered, for the first time, whether the existing international energy architecture remained adequate to meet the ever-growing demands of the world’s energy market, which by then accounted for nearly two-thirds of global emissions. They endorsed principles to guide collaboration on energy policy and aimed to phase out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies. Brisbane therefore validated the G20’s collective understanding that the world’s energy problems were also the world’s climate problems.

This uptick continued through to the 2017 Hamburg Summit. Despite the rift between the United States and its G20 partners on climate and energy, Hamburg produced a climate and energy plan through its goal of phasing out fossil fuel subsidies and shifting countries towards “affordable, reliable, sustainable and low greenhouse gas emission energy systems as soon as feasible”.

Unprecedented natural disasters and record-breaking temperatures throughout 2018 underscored the need to act collectively and decisively. At the 2018 Buenos Aires Summit, G20 leaders launched the first-ever Climate Sustainability and Energy Transitions steering committees, bringing together several G20 engagement groups to focus on adaptation, climate financing, sustainable consumption, flexibility, transparency and the digitalisation of energy grids. This format enabled more inclusive collaboration by addressing numerous energy principles, including those tied to better access, renewables, transparency, clean energy technologies and the phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies. But G20 leaders at Buenos Aires only dedicated 188 words – or 2% – of the total communiqué to energy.

Commitments

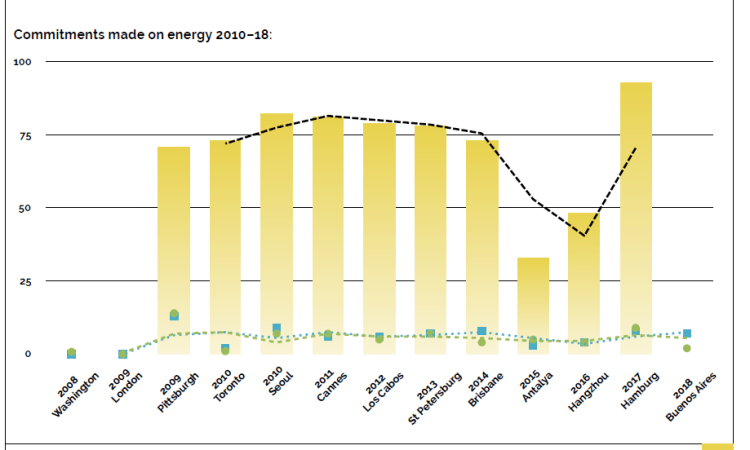

In all, the G20 has made 155 energy commitments. It made its first 16 at the 2009 Pittsburgh Summit. This dropped to one at the 2010 Toronto Summit, and rose to 14 at the 2010 Seoul Summit and 18 at the 2011 Cannes Summit. Ten commitments were made at the 2012 Los Cabos Summit, 19 at the 2013 St Petersburg Summit and 16 at the 2014 Brisbane Summit. The number dropped to three at the 2015 Antalya Summit and eight at the 2016 Hangzhou Summit. The highest number to date – 42 – was made at Hamburg in 2017. This spike was brief, as only eight commitments were made at Buenos Aires in 2018.

Compliance

The G20 Research Group has assessed 19 commitments on energy for compliance by G20 members, and found an average of 71%. Four commitments were assessed from the 2009 Pittsburgh Summit, averaging 71%. One assessed from the 2010 Toronto Summit averaged 73%. The three each assessed from the 2010 Seoul and 2011 Cannes summits averaged 82% and 81% respectively. One each assessed from the 2012 Los Cabos and 2013 St Petersburg summits followed closely at 79% and 78% respectively. There was a decline for the following three summits: two commitments assessed from the 2014 Brisbane Summit averaged 73%, one assessed from the 2015 Antalya Summit averaged 33%, and two from the 2016 Hangzhou Summit averaged 48%. There was, however, a spike to 93% for the one commitment assessed from the 2017 Hamburg Summit.

Prospects for Osaka

As leaders arriving in Osaka face domestic political pressures, it remains unclear what the G20 can realistically achieve in global energy governance. But as 2019 marks the 10th anniversary of the Pittsburgh G20’s declaration on eliminating fossil fuel subsidies, they have an opportunity to establish processes and timelines to redirect finances from fossil fuel subsidies towards support for cleaner, more sustainable and cost-effective energy practices and alternatives. The transition to a low-carbon future can become a reality if the G20 leaders provide the political and financial certainty to secure it.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Global Solutions Initiative. This article was originally published in G20 Japan: The 2019 Osaka Summit by GT Media Group and the G20 Research Group, 2019.