The G-20 and the broader world community has committed to ambitious goals to close global infrastructure gaps, mitigate climate change, and advance the 2030 Agenda for development. We call on G20 leaders to task development finance institutions (DFIs) such as the development banks in member countries and the Multi-lateral Development Banks (MDBs) of which G-20 countries are members, to commit to scaling up resources by 25 percent, to calibrate new financing to international commitments to mitigate climate change and the 2030 agenda, and to work together as an inclusive system toward achieving those shared goals.

Challenge

The world community needs to annually mobilize trillions of dollars in order to close infrastructure gaps and meet these broader goals and commitments. The private sector and national governments are falling far short of leading the way to financing these goals. DFIs are uniquely poised to provide and mobilze capital but the effort to date has been under-capitalized, under-performing, and uncoordinated.

Unmet global infrastructure needs to 2030 are over $3 trillion annually if they are to be conducted in a manner that is low carbon and socially inclusive.[1] What is more, the credit gap for micro, small and medium enterprises across the globe is upwards of $2 trillion.[2]

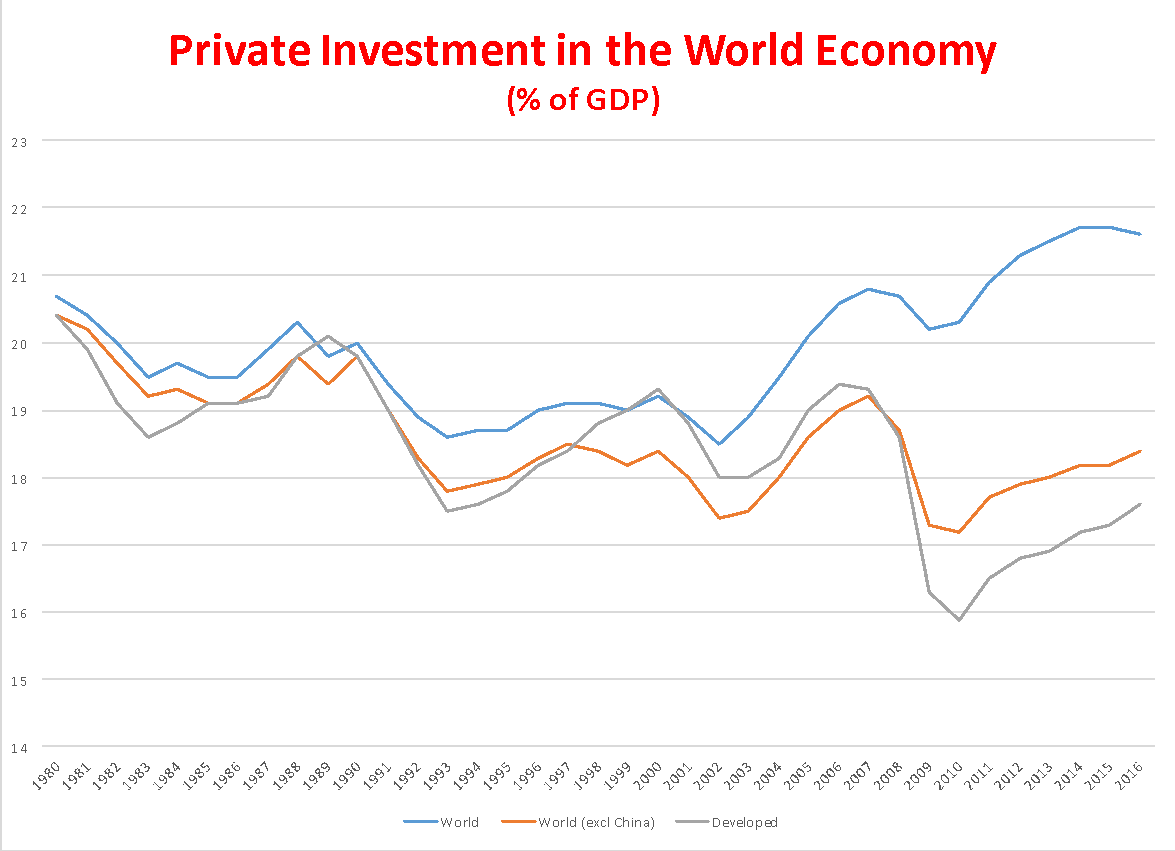

The private sector and national governments are doing little to address these gaps in long-run financing. Private capital flows are immense in scale but have proven to be biased toward short-term gains—flowing in ‘surges’ and unstable ‘sudden stops’ to emerging market and developing countries– rather than long term needs in infrastructure and human capital formation.[3] Private sector levels of investment in gross fixed capital formation have been small and on the decline for decades. In 1980 private sector investment as a percent of gross domestic product was over 20 percent, and has declined to roughly 18 percent (Appendix 1). New research by the International Monetary Fund shows that public investment in the form of fiscal policy by national governments also tends to be be biased toward short-term electorial cycles.[4]

Development Finance Institutions such as national and sub-regional development banks and multi-lateral development banks have a unique roll to play. These institutions can take a longer-run societal view toward financing, can uphold and demonstrate standards of excellence, and can mobilize commercial financing in tandem with their goals. However, many DFIs have been under capitalized and underperforming, and there is little coordination across all the DFI’s toward these common goals.

DFI’s across the world hold roughly $6 trillion in total assets, with G-20 members as shareholders of $4.3 trillion of that total. The largest amount of DFI capital is held in national development banks, which are $4.8 trillion of the total, and MDBs at $1.8 trilllion.[5] While significant, these assets are dwarfed by the size of the need and are not always aligned with broader development goals.

We face a great challenge to mobilize trillions more in capital to change the structure of the world economy to one that is more sustainable and socially inclusive.[6] Thus far, in bridging the infrastructure gap, MDBs have been done a limited job at mobilizing private capital peaking to just over $200 billion in 2010, and down to just $93 billion in 2017.[7] The Global Infractructure Facility, supported by the G-20 and the World Bank for public-private partnerships (PPPs), has attracted a mere $84 billion and committed just $37 million.[8] Of the limited mobilization that has occurred it is not clear that such resource mobilization has been pro-poor and has enhanced debt sustainability, and broader development goals.[9] DFIs will need to convene multi-stakeholder forums to align the public and private sectors in this regard.

[1]McKinsey Global Institute (2016). Bridging Global Infrastructure Gaps. McKinsey & Company; World Bank (2017). Global Infrastructure Outlook Report;

[2] Peer Stein, Oya Pinar Ardic and Martin Hommes, “Closing the Credit Gap for Formal and Informal Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises,” World Bank, August 2016,

[3] Barton, Dominic and Martin Wiseman (2013), “Investing for the Long Term,” McKinsey Global Institute; Rey, H., 2016, “International Channels of Transmission of Monetary Policy and the Mundellian Trilemma,” IMF Economic Review, 64(1), 6–35; Ocampo, Jose Antonio (2018), Reforming the International Monetary System, New York, Oxford University Press.

[4] International Monetary Fund (2017), Fiscal Politics, Washington, IMF.

[5] Gallagher, Kevin P. and William Kring (2017), Remapping Global Economic Governance, GDP Center Policy Brief 004, Global Development Policy Center, Boston University.

[6]Bazzi, Samuel, Rikhil Bhavnani, Michael Clemens, and Steven Radelet. “Counting Chickens When They Hatch: Timing and the Effects of Aid on Growth,”The Economic Journal, June 2012, 122: 590-617;Easterly, William (2001), The Elusive Quest for Growth:Economists’ Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics Cambridge MA: MIT Press; Buntaine, Mark (2016), Giving Aid Effectively: The Politics of Environmental Performance and Selectivity at Multilateral Development Banks, Oxford University Press,

[7] World Bank (2018), 2017 Private Participation in Infrastructure Annual Report, Washington, World Bank.

[8] World Bank (2018), Global Infrastructure Facility, Washington, World Bank, https://fiftrustee.worldbank.org/Pages/gif.aspx

[9] Intependent Evaluation Group (2014) World Bank Group Support to Public-Private Partnerships, Washinton, World Bank.

Proposal

We call on G20 leaders to task development finance institutions (DFIs) such as the development banks in member countries and the Multi-lateral Development Banks (MDBs) of which G-20 countries are members, to commit: to scaling up resources by 25 percent, to calibrate new financing to international commitments to mitigate climate change and the 2030 agenda, and to work together as an inclusive system toward achieving those shared goals.

Scale Up Development Finance

DFIs, especially the MDBs, will need a stepwise expansion and optimization of capital to meet our common goals. This can be accomplished by increasing the base capital of DFIs, expanding their lending headroom, and by mobilizing capital from the commercial sector.

DFIs will need to increase their base and callable capital and increase the lending headroom on their balance sheets to meet broader development goals. Since the global financial crisis some DFI’s have made significant increases to the amount of DFI capital in the world economy but a stepwise increase from these levels is still needed[1]. Chief among those contributions has come from China. Since the crisis China has increased the assets of the China Development Bank by $1.5 trillion, with roughly one-fifth of its balance sheet now in overseas financing to sovereign governments outside China. What is more, China has helped establish two new MDBs in the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the New Development Bank.[2] Many national and sub-regional development banks in emerging market and developing countries also replenished or created new DFIs as well as they accumulated reserves due to the commodity-boom in the aftermath of the crisis (Appendix 2). Recently, shareholders endorsed a $7.5 billion paid-in capital increase for International Bank for Reconstruction (IBRD) and Development and $5.5 billion paid-in capital for International Finance Corporationas well as a $52.6 billion callable capital increase for IBRD[3].

In addition to further capital increases, some DFIs have significant ‘lending headroom’ to provide more financing while continuing to maintain strong credit ratings. A number of recent studies, including a study by Standard and Poor’s rating agency itself, estimate that MDBs could increase their lending headroom by $598 to $1.9 trillion under various scenarios. Without a capital increase, if MDBs optimized their balance sheets at a AAA rating, the range of increase ranges from $598 billion to $1 trillion. With a capital increase of 25 percent by major MDBs, lending could expand by $1.2 to $1.7 trillion. If some MDBs were to optimize at a AA+ rating, expansion could reach close to $2 trillion dollars. In the later case however, optimizing at AA+ will have an negative impact on profitability though according to research to support this brief the net benefits are still likely to be positive.[4] In addition to expanding lending headroom, some DFIs are considering securitizing their loan portfolios, though there are few examples of DFI securitization and estimates of the benefits and costs of such an approach not yet forthcoming[5].

There is potential to further bridge financing gaps through blended finance and PPPs, and DFIs can play a key role in mobilizing the much needed public and private capital to finance sustainable infrastructure [6]. Blended finance has been defined as “the strategic use of development finance and philanthropic funds to mobilize private capital flows to emerging and frontier markets” using such instruments as guarantees, securitization commercial bank loans, syndicated loans, credit lines, direct investments in companies, credit enhancement of project bonds, and shares in special purpose vehicles.

Private participation in infrastructure projects has been promoted for many years through PPPs and are now foscusing on the design of financial instruments to develop infrastructure as an asset class. Unfortunately, relative to the size of the gaps private finance of infrastructure is falling short. Blended finance has mobilized only $31 billion through blended financing efforts since 2000[7]. As noted earlier, there is promise in PPPs, though should not be overblown. As noted earlier,private participation in infrastructure projects has also been relatively small. The majority of that financing has gone to developed and large middle-income countries. Only 24 of the poorest countries had a single infrastructure project with private participation between 2011 and 2015[8]. The Inter-Agency Task Force on Financing for Development found that of the close to $50 billion mobilized by MDBs in private co-financing, only US$1 billion flowing to least developed countries and little evidence that the most vulnerable in those countries were beneficiaries[9].

Finance for Development

Echoing the G-20 Eminent Persons Group, DFI “governance structures and internal incentives should be reoriented towards achieving development impact, rather than deployment of their own financing.[10]” Maximizing finance for development is not the same thing as optimizing development bank finance under a ‘business as usual’ scenario. Current infrastructure is responsible for the majority of carbon dioxide emissions and lays the foundation for much of the unsustainable production and consumption patterns and accentuates exisiting inequities in much of the global economy today.[11]

Adapting to country and regional circumstances calibrating new finance to Agenda 2030 and the Paris agreements should be the guiding rationale for new financing. What is more, DFIs will need to deploy new measurement and monitoring systems that ensure that DFI’s maximize the development impacts and mitigate the development and financial risks of their efforts for better development effectiveness. Key to measuring and monitoring progress is the need to increase transparency for measurement, evaluation, and accountability. Member states of the United Nations have agreed to collect a set of global indicators to be developed by the Inter-agency and Expert Group on Sustainable Development Goal Indicators (IAEG-SDGs), indicators that can serve as a set of common agreed upon statistics that DFI financing can be calibrated toward and measured against[12]. Adopting a clear and inclusive process to measure DFI progress for accountability will be critical to achieving Agenda 2030.

Some DFIs are leading on climate change commitments by pledging to provide disincentives for economic activity that accentuate climate change while simultaneously encouraging climate friendly activity. Many of the MDBs have strong limits on the financing of coal fired power plants, and the World Bank has pledged to end financing for upstream oil and gas extraction by 2019[13]. The Inter-American Development Bank has pledged to all projects for relevant climate risks starting in 2018, and the Caribbean Development Bank has explored the adoption of ‘climate-stress testing’ of their entire balance sheet to protect it from climate-related stranded assets[14]. Brazil’s national development bank and the Development Bank of Southern Africa have created special climate funds. The China Development Bank has been active in green bond markets, issueing a $500 million bond certified by the Climate Bond Initiative for low carbon wind, transport and water projects in China and Pakistan.

Strengthened and improved Environmental and Social Risk Management systems (ESRM) beyond those that examine climate change will be essential to ensuring that development financing is calibrated toward broader goals. While most development banks deploy ESRM, the quality and degree to which these systems are effective varies widely. Especially in the case of MDBs, ESRM has been perceived by host country finance ministries and by operations staff at MDBs as onerous conditionalities that slow project approval and completion without necessarily improving social and environmental outcomes[15]. Other work has shown that some safeguards, such as environmental impact assessments, grievance mechanisms, and ‘free prior informed consent’ by local communities help DFIs identify and mitigate risk and improve project outcomes.

Some DFIs, such as the Development Bank of Latin America, the KfW of Germany, the Caribbean Development Bank, and and the have a unique approach whereby they provide grant and concessional financing as well as technical assistance to borrowing countries to establish effective ESRMs at the project level, enhancing the institutional capabilities of borrowing nations rather than imposing conditions without corresponding financing[16]. DFIs will need to strengthen and improve ESRMs appropriate to country and regional circumstances and in calibration with broader development goals by promoting a multi-stakeholder dialogue in this regard..

A new set of principles and guidelines will need to be created to ensure that PPPs and blended finance approaches are calibrated to Agenda 2030 as well. A recent UN assessment evaluated the guidelines of 12 major institutions including the OECD, World Bank, IMF and others and found that the guidelines do not yet align with Agenda 2030. Across the guidelines there is a lack of clear guidance regarding when PPPs are appropriate and when they are not, how to align with national process & international commitments, guidance on the Fair sharing of risk and rewards, alignment with sustainable development / SDGs; Climate, human rights considerations, and how to incorporate various Stakeholder perspectives.

A next generation of PPPs should be driven to align with Agenda 203o and Paris. For this to occur, the study concludes, “governments must consistently strive to realize broad public value and public good from PPPs. This means the public must be at the center of PPP deliberations, decision making and delivery. Governments must engage with citizens, weigh the socioeconomic costs and benefits of PPPs, and put in place appropriate institutional and accountability mechanisms, systems, processes, and capacity to achieve the fuller vision. As part of PPPs, commercial actors must also commit and be subject to adopting appropriate standards that aligning with broader goals[17].”

Global Cooperation and Governance

The G-20 should encourage the establishment of a multi-stakeholder forum that includes not soley national governments and MDBs, but also the broader set of DFIs, the business community, civil society, and other key stakeholders into a cooperative process. While there are a number of separate forums and platforms for DFI collaboration, there lacks a global forum for DFI dialogue, cooperation, coordination, and collaboration among relevant stakeholders. The World Federation for Development Financing Institutions (WFDFI) and its regional chapters is the most systematic set of groupings among DFIs, especially for national development banks. The International Development Finance Club (IDFC) is the most comprehensive attempt to bring together both national development banks, subregional development banks, and some MDBs such as the Islamic Development Bank. Of course, as part of the annual and spring meetings of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund the larger Western-backed MDBs convene and at times coordinate.

From these efforts have been a number of initiatives that could be scaled and replicated across a broader global system. The IDFC negotiated a pledge to generate $100 billion in green financing and developed an aligned tracking and monitoring system and then negotiated a set of ‘Common Principles for Climate Mitigation Finance Tracking’ and now regularly report on progress[18]. The Inter-American Development Bank, in part drawing on support from joint funds between China’s development banks and central bank and the IDB, has a program with members of Latin American Association of Development Financing Institutions (ALIDE), the Latin American regional grouping of the WFDFI to on-lend, credit enhance, and provide technical assistance to national development banks in the Americas for clean energy and energy efficiency, ESRM, and have created a ‘Green Finance in Latin America’ platform[19]. Deploying a similar model, the New Development Bank of the BRICs countries raises funds on green bond markets and on-lends for sustainable infrastructure to national development banks in member countries[20]. Germany’s KfW is working with the International Renewable Energy Association to establish a regional liquidity facility for renewable energy infrastructure, and the KfW and France’s AFD have had credit facilities with the Development Bank of Latin America for some time[21].

There are limitless opportunities and agendas for a global forum of coordination and cooperation across DFIs. Shared country strategies, the development of regional approaches (especially for infrastructure), dialogue on safeguards and standards, could all be part of such an agenda. Over time some of the best practices discussed above could be scaled up. Proposals for such cooperation include a global special purpose vehicle and global guarantee funds for sustainable infrastructure, and the creation of project platforms to facilitate crowding-in private investment, among others[22].

A global forum for DFIs could also help foster a more global representation of the stakeholders of the development process. Quoting from a recent report on the subject that success may depend on “A vision of a system serving all developing countries requires a governance structure that permits adequate voice[23].” given that research shows how “ when borrowing countries have more voice have: less reliance on a compliance rules-based culture, and more cost-effective linkage between safeguards and development benefits; less conservative financial policies; more flexibility in allocation procedures; and less internal oversight and cost[24].” Aligning national development banks, borrower-led sub-regional DFIs, and the MDBs as well as with civil society participation would provide for a more cohesive and legitimate system to coordinate, and calibrate global DFI financing toward our common future.

Appendix 1[25]

Appendix 2[26]

[1] Bhattacharya, Amar, et al, (2018), The New Global Agenda and the Future of the Multilateral Development Bank System, Washington, Brookings Institution.

[2] Gallagher, Kevin P. and William Kring (2017), Remapping Global Economic Governance, GDP Center Policy Brief 004, Global Development Policy Center, Boston University.

[3] World Bank (2018), Press Release: World Bank Group Shareholders Endorse Transformative Capital Package, April 21, 2018. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2018/04/21/world-bank-group-shareholders-endorse-transformative-capital-package

[4] Humphrey, C. 2015. “Are Credit Rating Agencies Limiting the Operational Capacity of Multilateral

Development Banks?” 30 October 2015. Paper Commissioned for the Inter-Governmental Group of 24. Washington DC: G24; Humphrey, C. (2018), “The Role of Credit Rating Agencies in Shaping Multilateral Finance, Paper Commissioned for the Inter-Governmental Group of 24. Washington DC: G24; Settimo, R. 2017. “Towards a More Efficient Use of Multilateral Development Banks’ Capital.” Occasional Paper Series 393, September 2017. Rome: Bank of Italy; S&P Global Ratings. 2017b. “Key Considerations for Supranationals’ Lending Capacity and Their Current Capital Endowments.” 18 May 2017. New York: S&P Global Ratings; Munir, Waqas and Kevin P. Gallagher (2018), Scaling Up Lending at the Multilateral Development Banks, GEGI WORKING PAPER 013

Global Development Policy Center, Boston University USA.

[5] Humphrey, Christopher (2018), Channeling Private Investment to Infrastructure: What Can MDBs Realistically Do? London: Overseas Development Institute, Working Paper 534

[6] Humphrey, Christopher (2018), Channeling Private Investment to Infrastructure: What Can MDBs Realistically Do? London: Overseas Development Institute, Working Paper 534;

[7] OECD (2018), Making Blended Finance Work for the Sustainable Development Goals, Paris, OECD; Humphrey, Christopher (2018), Channeling Private Investment to Infrastructure: What Can MDBs Realistically Do? London: Overseas Development Institute, Working Paper 534; Lee, Nancy (2018), Billions to Trillions? Issues on the Role of Development Banks in Mobilizing Private finance, Washington, Center for Global Development.

[8] Humphrey, Christopher (2018), Channeling Private Investment to Infrastructure: What Can MDBs Realistically Do? London: Overseas Development Institute, Working Paper 534; Ruiz-Nuñez, F. and Z. Wei (2015) Infrastructure Investment Demands in Emerging Markets and Developing Economies. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 7414. Washington DC: World Bank.

[9] Inter-Agency Task force on Financing for Development (2018), Financing for Development Progress and Prospects 2018, New York, United Nations.

[10] Eminent Persons Group, G-20 (2018), G20 Eminent Persons Group (EPG) on Global Financial Governance: Update for the G20 Meeting of Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, https://g20.org/sites/default/files/media/epg_chairs_update_for_the_g20_fmcbgs_meeting_in_buenos_aires_march_2018.pdf

[11] Davis, Steven, Steven J. Davis, Ken Caldeira, Damon Matthews, “Future CO2 Emissions and Climate Change from Existing Energy Infrastructure Science 10 Sep 2010:Vol. 329, Issue 5997, pp. 1330-1333; Bhattacharya, Amar, Jeremy Oppenheim, Nicholas Stern (2016), Driving Sustainable Development Through Better Infrastructure: Key Elements of a Transformation Program, Washington, Brookings Institution, New Climate Economy.

[12] Inter-Agency Task force on Financing for Development (2018), Financing for Development Progress and Prospects 2018, New York, United Nations.

[13] Piccio, Lorenzo (2016), To Coal or Not to Coal? A Balancing Act for MDBs, DevEx, https://www.devex.com/news/coal-or-no-coal-a-balancing-act-for-mdbs-87610; World Bank (2017), World Bank Announcements at One Planet Summit, Washington, World Bank, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2017/12/12/world-bank-group-announcements-at-one-planet-summit

[14] Inter-American Development Bank (2017), Delivering a Climate Agenda for Latin America, Washington, Inter-American Developmetn Bank; Stefano Battiston, Antoine Mandel, Irene Monasterolo, Franziska Schütze, and Gabriele Visentin, “A Climate Stress Test for the Financial System,” Nature Climate Change volume 7, pages 283–288 (2017); Monasterolo, I., Battiston, S. (2016). Assessing portfolios’ exposure to climate risks: an application of the CLIMAFIN-tool to the Caribbean Development Bank’s projects portfolio. Final deliverable Technical Assistance for Climate Action Support to the Caribbean Development Bank TA2013036 R0 IF2.

[15] Humphrey, Chris (2016), Time for a New Approach to Environment and Social Protection at Multilateral Developmetn Banks, London, Overseas Development Institute; World Bank. (2010). Safeguards and sustainability policies in a changing world. Independent Evaluation Group. Washington, DC:

[16] Yuan, Fei, and Kevin P. Gallagher (2017), “Standardizing Sustainable Development: A comparison of development banks in the Americas,” Journal of Environment & Development 2017, Vol. 26(3) 243–271

[17] Aizawa, Motoko (2018), “A Scoping of PPP Guidelines,” DESA Working Paper 154, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

[18] IDFC (2015), “Common Principles on Climate Mitigation Financing,” Germany, IDFC, International Development Finance Corporation, https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/65d37952-434e-40c1-a9df-c7bdd8ffcd39/MDB-IDFC+Common-principles-for-climate-mitigation-finance-tracking.pdf?MOD=AJPERES

[19] Inter-American Development Bank (2018), Green Finance for Latin America, Washington, IDB, https://www.greenfinancelac.org/projects-map/

[20] New Development Bank (2017), NDB’s General Strategy, 2017-2012, Shanghai, New Development Bank, https://www.ndb.int/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/NDB-Strategy-Final.pdf

[21] International Development Finance Club (2016), Moving from Triangular Cooperation to Cooperation for Development: New Initiatives for Deepening IDFC Collaboration, Germany, KfW, IDFC; Griffith-Jones, Stephanie (2016), National Development Banks and Sustainable Infrastructure, the case of the KfW, GEGI Working Paper 006, Global Development Policy Center, Boston University, USA.

[22] Lee, Nancy (2018), More Mobilizing, Less Lending: A Pragmatic Proposal for MDBs, Washington, Center for Global Development; Studart, Rogerio, ad Kevin P. Gallagher (2018), Guaranteeing Sustainable Infrastructure, Journal of International Economics, (forthcoming).

[23] Bhattacharya, Amar, et al, (2018), The New Global Agenda and the Future of the Multilateral Development Bank System, Washington, Brookings Institution.

[24] Homi Kharas, “The Post-2015 Agenda and the Evolution of the World Bank Group,” The Brookings Institution, GED Working Paper 92, September 2015

[25] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2017), Trade and Development Report, 2017), Geneva, United Nations.

[26] Gallagher, Kevin P. and William Kring (2017), Remapping Global Economic Governance, GDP Center Policy Brief 004, Global Development Policy Center, Boston University.