High-order cognitive skills, such as creativity and critical thinking, will face burgeoning demand as a result of digitalization and technological innovations. To build the workforce of the future and diminish future inequalities within and among countries, educational systems must close the education-workforce divide. In other words, they must integrate unforeseeable social and work demands into schools’ practices to ensure that students, especially those from impoverished backgrounds, develop the skills to participate in their local economies and democracies. Hence, supporting functions must be in place at the highest levels of government in order for G20 countries timely and equitably meet the needs and aspirations of children and youth while facing market changes. In this context, equal emphasis must be allocated to competency based curriculum reforms, teacher professional development and evaluation mechanisms.

Challenge

Recent G20 communiques of 2017[1] have addressed key issues related to the future of work, specifically issues related to digital innovations and labor market transformations. Yet, little attention has been given to supply mechanisms responsible to build the needed competencies and skills to address the volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous transformations in labor markets and society as a whole: school systems.

To bridge the Education-Workforce Divide and mitigate future inequalities, supporting functions must be in place to tailor and improve curriculum redesign processes and teacher professional development at all levels of education across G20 countries. Such mechanisms must be implemented to provide children and youth with opportunities for deep learning and skills development as part of students’ basic school life cycles.

The Education-Workforce Divide is characterized by the paucity of malleability of school systems to adapt to rapidly changing economies and by unprecedented labor market developments resulting from novel trends such as automation and technological advancements. On one hand, school systems in both developed and developing countries have not yet been able to develop children’s and youth’s skills and competencies for further participation in economic and civil activities, which has been evidenced by international instruments such as PISA (The Programme for International Student Assessment) (Gurria, 2016). On the other hand, technological changes promote labor market disruptions that widens the very Education-Workforce Divide, creating further challenges for democracies as a result of higher inequality rates (International Labour Organization, 2018). Although it is unclear how much disruptions one must expect from these shifts, certain estimations point out to a 60 per cent job automatization by 2030 (Balliester & Elsheikhi, 2018).

The Education-Workforce Divide affects youth and children and may become a greater pressing issue for G20 countries in years to come. The global youth unemployment rate was 13.1 percent in 2017 (International Labor Organization, 2017), and three out of four youth who were employed worked in the informal economy (International Labor Organization, 2017), which may increase the vulnerability of the poor due to a paucity of safety nets (World Bank, 2013, p. 129). Moreover, according to International Labor Organization estimations, more than one-fifth of youth are not employed or developing any kind of educational or training activity (ILO, 2017). Together with unmalleable school systems and rapidly market changes, such estimations may skyrocket and create unforeseeable social and economic challenges for G20 societies and democracies.

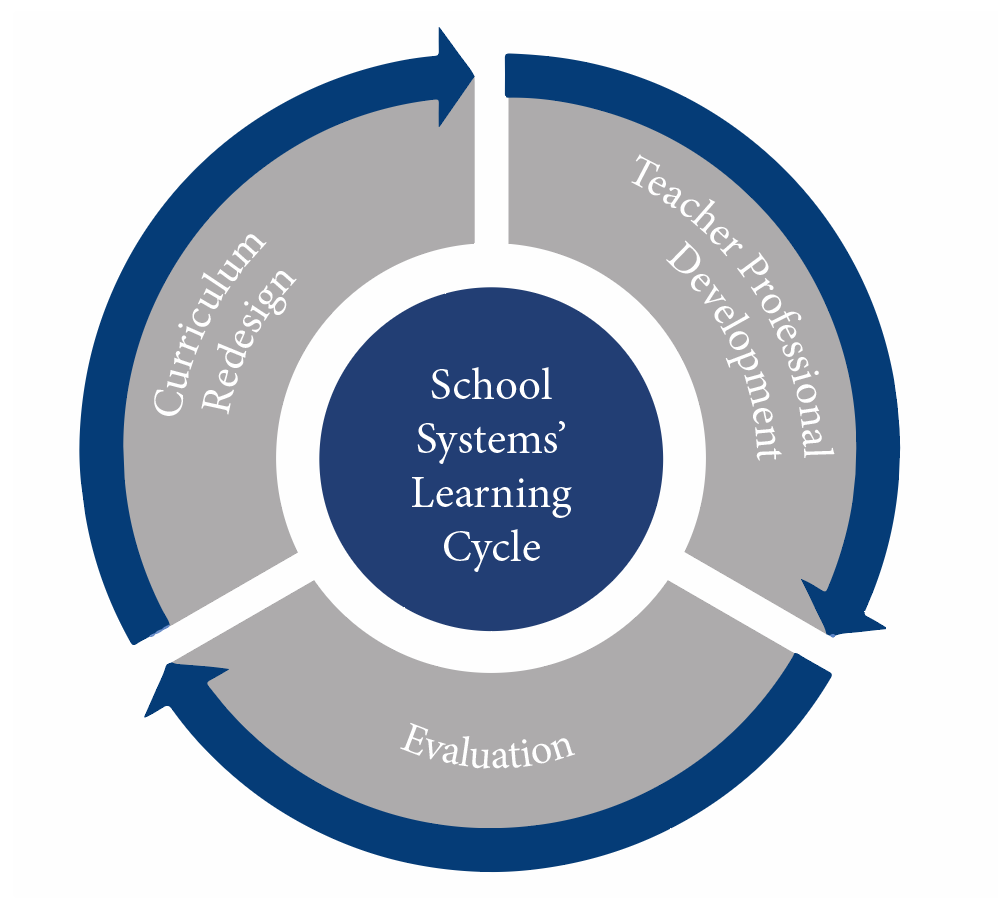

Recognizing that labor market disruptions will continue to shape economies G20 economies, that the transition from school to work may become increasingly difficult, and that policymakers have the capability to craft educational policies to support school systems to become malleable and prepare students to deal with such complexity, this policy brief draws recommendations for G20 countries to tailor and improve curriculum redesign processes, teacher professional development and evaluation mechanisms. These are three key policy areas that may support G20 countries to help educational systems become more malleable, narrowing the Education-Workforce Divide and providing children and youth with high-quality resources for skills development during their basic school life cycle.

[1] https://www.g20-insights.org/policy_area/future-of-work/

Proposal

G20 countries must ensure that children and youth, especially vulnerable ones, have the opportunities to acquire and develop the interpersonal, intrapersonal and cognitive skills for citizenship and work during early childhood, primary and secondary education. Basic education is one of the few paths that vulnerable children have out of poverty (World Bank 2013). Thus, in order for G20 countries narrow the Education-Workforce Divide, it is pivotal that school systems become malleable to societal and market signals and prepare students to contribute civically and economically to their communities.

It is in this context that curriculum reform and teacher professional development become central to close the Education-Workforce Divide. With the support of high-quality resources in schools – especially a curriculum that is able to develop the whole child and teacher professional development tailored to developing skills – children and youth may become more likely to deal with the complexity of today’s and tomorrow’s world and actively contribute to the advancement of G20 economies and democracies.

On one hand, the curriculum establishes the kinds of knowledge and competencies to be mastered for civic and economic participation, as well as the types of activities that children and youth may experience during their school life cycle to develop these same competencies. On the other hand, teacher professional development prepares teachers to bring this curriculum to action and foster these competencies equitably in classrooms. However, curriculum redesign processes and teacher professional development mechanisms are diverse and may not always lead to these expected outcomes. Moreover, incongruent and divergent evaluation mechanisms may hinder the process of collaborative learning across G20 countries.

Consequently, supporting functions must be in place to guarantee that curriculum is designed to avoid content overload while ensuring quality content and equitable implementation, in addition to timely meeting society’s social and economic needs. Moreover, teacher professional development must be aligned with national and subnational curricula, providing teachers with time, teaching resources and space for collaboration to hone teaching practices that can truly enhance and shape students’ knowledge and skills, in addition to evaluation mechanisms that can inform such practices across G20 countries creating a school system learning cycle.

Supporting Functions to Foster

School’s Malleability and Mitigate Future Inequalities

Vision 1 – Supporting Function One: Curriculum Redesign

In order to map societal and market needs and technological advancements, government entities, such as the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Labor and Ministry of Innovation and Technology of G20 countries, should articulate with one another and integrate a joint committee, workforce or entity, together with civil society and other key stakeholders, to reach out to labor markets and map the demand for different types of knowledge, skills and technological advancements.

Such committee must be responsible to inform current and future curriculum redesign initiatives carried out by the Ministry of Education; benchmark local and national standards to ensure quality of curriculum content; curate the curriculum to avoid content overload and to allow for differentiation; align national and subnational curriculum for equitable implementation, and provide ongoing technical assistance to such efforts.

Once the curriculum is being implemented, the committee must reconvene, especially after the first cohort of students experiencing the new curriculum finish the basic school cycle. It should study the educational outcomes from these efforts through formative and summative assessments, map novel economic and social trends, compile lessons learned and amend the curriculum and teaching resources. Lessons regarding the national redesigning of curriculum to transform school systems at scale may be shared with G20 countries, which may or may not be carrying out their own curriculum reforms, to improve their practices and inform policy making on an ongoing basis.

Vision 2 – Supporting Function Two: Teacher Professional Development

For teachers to bring the curriculum to action in classrooms, and allow every student at every classroom to develop the skills and competencies for the future of work and citizenship, it is pivotal that they also hone these skills on an ongoing basis, learning to cultivate experiences in classrooms to develop these skills in their students too. To accomplish this, effective teacher professional development must be in place from the moment teachers enter the profession. This is the lever of change that allows teachers to evaluate their practice and learn from peers what can be most effective to foster the process of learning and skills development.

The teacher professional development must be content focused, incorporate active learning as part of their pedagogy, supports collaboration, uses models of effective practice, provides coaching and expert support, offers feedback and reflection and be of sustained duration (Darling-Hammond, Hyler, & Gardner, 2017). Moreover, as previously suggested, teacher professional development must be aligned with curriculum and evaluation systems. For example, through collaboration – the act of working together with others – teachers may be able to develop their leadership and communication skills while taking advantage of opportunities to learn new teaching sequences that are known to be effective with students, as evidenced by their own evaluation systems. Each G20 country must evaluate whether the professional development in their schools possess these ingredients for success and, most importantly, assess whether these initiatives are yielding the expected results in terms of students learning and skills development. Such lessons may be shared with other countries to improve their practices and inform policy making on an ongoing basis.

Vision 3 – Supporting Function Three: Evaluation Mechanisms

One of the greatest challenges facing G20 countries is to create cohesion by aligning measurement parameters to inform practice and monitor skills’ development, especially those placed in the social emotional domain. Once established, these evaluation mechanisms can be applied to teacher professional development and classrooms. In fact, to comprehensively inform the debate across G20 countries, it is germane that evaluation is cohesive among nation-states and that they are used to inform school practices.

G20 countries should aim toward the creation of cohesive national evaluation indexes and decide how they will define, measure and monitor the development of skills. For example, among other matters, governments have to determine whether they will focus on biometric, psychometric and experimental evaluation methods of social emotional skills, the frequency in which this data will be collected, as well as its validity and reliability mechanisms.

Each Ministry, based on the needs of the country and on the mapping of the demand for different types of skills, can determine the types of skills that need to be developed and acquired in their school systems, respecting their own local contexts. Based on this information, G20 countries can use the index to determine how they will measure and collect this information, build lessons and share these system wide, informing policy making on an ongoing basis.

Overall Vision

Altogether, these functions operate to support G20 educational systems become more malleable to ever changing societal and economic transformations, allowing schools to improve their practices and tailor them to skills development. This way, its populations of children and youth will be able to build human capital and support their economies and democracies, thus mitigating future inequalities.

References

- Balliester, T., & Elsheikhi, A. (2018, March). The future of work: A literature review. International Labour Organization. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—inst/documents/publication/wcms_625866.pdf

- Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

- G20. (2017). Task Force: The Digitalization [HTML]. Retrieved April 16, 2018, from https://www.g20-insights.org/policy_area/future-of-work/

- Gurria, A. (2016). Pisa 2015 Results in Focus. PISA in Focus, (67), 1.

International Labour Organization. (2018, February 17). The Impact of Technology on the Quality and Quantity of Jobs. International Labour Organization. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—cabinet/documents/publication/wcms_618168.pdf - World Bank. (2013). World Development Report 2014: Risk and Opportunity – Managing Risk for Development. The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-9903-3