Focusing on critical aspects of infrastructure, such as energy, this brief argues that Africa, and African cities in particular, need infrastructure that advances both basic needs and industrialization, and avoids a lock-in of unsustainable, high-carbon technologies. G20 countries can promote and support quality of life in Africa by: (1) aligning and cementing the G20 Agenda for Africa with African initiatives, SDGs and the Paris Agreement, (2) mitigating economic risks of climate change through supporting low carbon development pathways in Africa, (3) creating and enabling a level playing field for low carbon technologies, which includes integrated strategies for de-risking renewable energy investments, and (4) supporting smart and sustainable urban planning. [1]

Challenge

Africa is vulnerable to climate change[2]’[3]. This is compounded by the continent’s limited capacity for both climate mitigation and adaptation[4]. Combined with the pressures of a rapidly growing and increasingly demanding population, it might be tempting for Africa to pursue a one dimensional strategy aimed at fueling growth, while relegating environmental concerns for later consideration[5]. This was the essence of development strategies pursued by both Western industrialized countries and their followers in East Asia and elsewhere[6]. If the African continent adopts a similar approach, the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) becomes very unlikely, particularly SDG 7, 11 and 13, which focus on sustainable energy, cities and climate action, respectively.

African countries need to industrialize in order to simultaneously achieve economic progress and the reduction of the continent’s high levels of poverty. It is also clear that boosting the power infrastructure, and extending its distribution network, are prerequisites for African industrialization. This is the aim of SDG9 on industry, innovation and infrastructure. To meet all the SDGs concurrently, the development of renewable energy in sub-Saharan Africa is desirable[7]. Scaling-up the exploitation of these energy sources may represent an economically feasible and sustainable development pathway. The African Renewable Energy Initiative (AREI), as initiated by the African Union and supported by the G7 and G20, is a strong case in point (and relates directly to SDGs 7 and 13). Conversely, the further expansion of fossil-based production comes with an increasing risk of stranded assets, dependence on imported processed fuels, the build-up of capacities in declining economic sectors and an increase in greenhouse gases and air pollution[8].

The G20 initiative in support of investment and infrastructure in Africa needs to take these climate and energy-related concerns into consideration or it risks promoting unsustainable development paths, which are likely to prove costly in the medium-term. To ensure that the G20’s proposed Africa strategy supports sustainable investments in infrastructure, this policy brief makes the following four recommendations:

- Aligning the G20 agenda for Africa with the SDGs and African initiatives: Support for investment in Africa should ensure alignment with the SDGs and the Paris Agreement as well as existing African initiatives. Of particular relevance in this regard are the African Union’s Agenda 2063 and the Africa Renewable Energy Initiative (AREI).

- Mitigating the economic risks of climate change by supporting African low-carbon development pathways: Africa needs a forward-looking approach to energy infrastructure development, which avoids lock-ins in high-carbon assets and is adapted to changing climatic conditions. Clean cook stoves represent an underexploited opportunity for supporting socio-economic benefits while also mitigating climate change.

- Leveling the playing field for a low-carbon energy transformation: The phasing out of fossil fuels offers an important opportunity to level the playing field for investments in low-carbon energy infrastructure. It would also relieve fiscal pressure on African governments. It should go hand-in-hand with integrated strategies for de-risking renewable energy investments.

- Supporting smart and sustainable urban planning: Creating inclusive cities with adequate infrastructure and services for all residents is critical. Investment and drive towards sustainable housing, infrastructure, transportation, energy and employment, and basic services such as education and healthcare is key for Africa.

Proposal

Africa’s Energy challenge

In sub-Saharan Africa, about 65 percent of the population (680 million people) lack access to electricity and 81 percent of the population relies on traditional biomass[9] as an energy source. The use of fuel wood and charcoal contributes to deforestation and which in turn reduces carbon sequestration by forests, causes soil degradation, decreases climate resilience, and increases disaster risk.

The challenge of improving access to modern energy services needs to be understood in a broader sense, i.e. beyond covering pure basic needs[10]. Energy access should be extended for productive purposes. The reliable provision of electricity and other modern fuels could be a precondition for the improvement of productivity in agriculture, industry or mining sectors. In addition, access to energy influences the use of modern domestic appliances and services, such as cooling or heating. This also corresponds to an increased adaptive capacity of the society to climate change impacts. For example, electricity is fundamental to limit the impact of drought in agriculture, and cooling appliances mitigate side effects of heat waves on health. However, increasing access to energy that goes beyond basic needs will generate increasing energy demand, which in the past has often been accompanied by increasing GHG emissions.

Basic needs

Despite the non-linear nature of shifts from traditional to modern fuels, incremental levels of access to energy services can enhance economic growth and welfare. The positive effects of basic energy access on welfare include productivity, health, gender equality and education[11], even though the effects are not always proven to hold in the African context[12]. Providing universal access to both electricity and clean cooking devices could save 0.4 million premature deaths (in 2030) that might otherwise be attributed to the use of biomass and other solid fuels, such as charcoal[13]. In order to achieve universal access in sub-Saharan Africa, investments of USD 19–40 billion per year up until the year 2030 would be required. However, in order to achieve this goal, countries in sub-Saharan Africa would need to undergo unprecedented rates of improvement in energy access, contrary to historical observations in other countries and regions[14]. It is important to note that providing basic energy access will lead to very limited additional GHG emissions[15].

Productive use and modern society needs

A large number of studies have empirically assessed the drivers of energy use and emissions from a global cross-country perspective and find that developing countries’ economic convergence to richer countries’ income levels and economic structures, is accompanied by convergence of energy use patterns (rather than decoupling)[16],[17]. Societies that have achieved high levels of human development all show final energy demands of more than 40 GJ per capita per year, which is far from being achieved in most sub-Saharan African countries[18]. While there is no doubt that energy consumption in industrialized countries needs to decrease, there is broad agreement that development will not be possible without its increase in most African countries. A range of technological solutions will have to contribute to needs-oriented supply. While off-grid applications such as solar can be an affordable and clean alternative, they will not be able to cover the full range of household and productive energy needs[19]. They thus need to be complemented by mini- and on-grid solutions.

A sustainable energy agenda

Developing an energy system that can provide reliable electricity, sustainably and at sufficient levels to the entire population is an ongoing challenge. Poor, but fast growing countries have traditionally invested increasingly in coal use[20], and recent investment patterns of sub-Saharan African countries follow this trend[21],[22]. Given that sub-Saharan African countries face massive investment needs in power generation capacity in the near future, covering a large share of this demand with fossil fuels, such as coal, will lead to severe lock-in effects that can endanger ambitious international climate targets or run the risk of being stranded. In the absence of climate policy, (continental) Africa’s emissions will increase 7 to 15 times by 2100, accounting for 3-23% of global emissions[23],[24].

Africa’s urbanization challenge

Africa is experiencing a fast urbanization process. In 2014, 40 percent of the population was living in urban areas; this will probably rise to 56 percent in 2050. Sub-Saharan Africa will show similarly high urbanization rates growing from 37 percent in 2014 to 55 percent in 2050[25]. The downsides of this rapid urbanization are already evident: in 2010, 60 percent of the urban population in sub-Saharan cities lived in slums with no access to basic services[26].

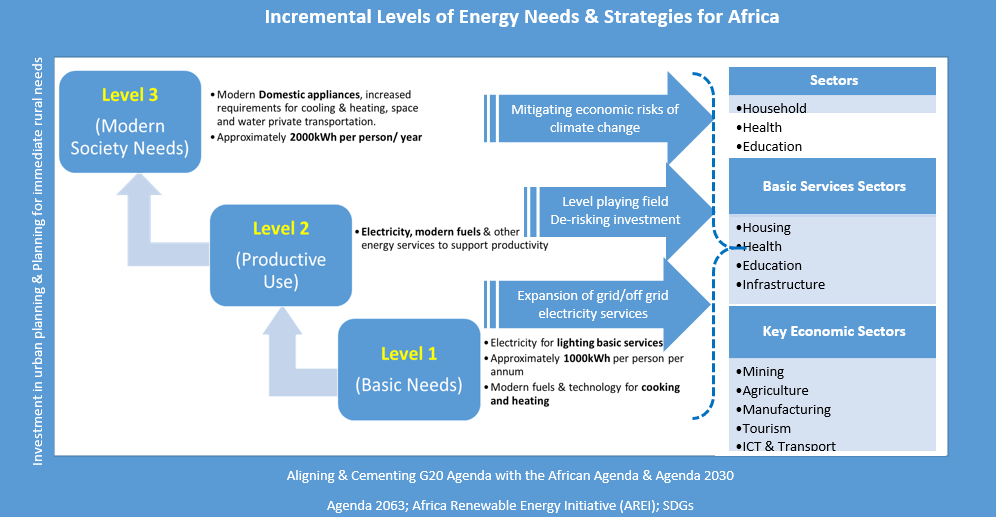

Making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable – as demanded by the SDGs – is a cross cutting challenge for the improvement of energy access and improvement of the quality of life in Africa. The construction of new urban infrastructure and climate resilient human settlements will not only require a large level of energy that is embedded in materials, such as steel and concrete. Due to its longevity and potentially carbon-intensive nature, the extent and form of urban infrastructure will also determine levels of energy use and hence emissions for decades to come. A smart and sustainable urban planning has a decisive role in shaping African cities and requires investments in energy saving infrastructures, the provision of basic services and the greening of the energy and transport sectors[27]. In the context of African urbanization, cities play a particularly important role when it comes to decreasing the demand for charcoal. This in turn affects both human health and deforestation. Additionally, urbanization patterns in Africa are challenging as cities increasingly eat into the most productive lands, which challenges food supply in the future[28]. Figure 1 illustrates incremental levels of access to energy and the proposed recommendations, which are described later in this brief.

RECOMMENDATION 1: ALIGNING THE G20 AGENDA FOR AFRICA WITH THE SDGS AND AFRICAN INITIATIVES

The German G20 Presidency has placed support for investment in Africa high on its agenda, calling for a “Compact with Africa”[30]. It intends to improve the investment climate as a catalyst for private investment. It is essential that these measures are closely aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement to ensure that new infrastructure investments place African countries on sustainable development pathways, avoiding potentially costly lock-ins in unsustainable, high-carbon infrastructure. In practical terms, this means that investment partnerships to be negotiated in the G20 Finance Track should be linked to a broader development agenda, which explicitly accounts for the challenges of climate change and sustainable development.

Moreover, such investment partnerships should build on existing African initiatives, such as the African Union’s Agenda 2063 and Africa Renewable Energy Initiative (AREI). A mapping of major energy initiatives in Africa conducted on behalf of the African Union, the Africa-EU Energy Partnership (AEEP) and Sustainable Energy for All (SE4ALL) provides an overview of the large number of existing initiatives in the energy sector[31]. The Africa Renewable Energy Initiative (AREI), for instance, aims to scale up renewable electricity in Africa by at least 300GW by 2030. Any new support schemes should take into account the existing landscape of initiatives and programs and should build on and expand existing initiatives. Existing information should be utilized to identify and close existing gaps in programming.

RECOMMENDATION 2: MITIGATING THE ECONOMIC RISKS OF CLIMATE CHANGE BY SUPPORTING AFRICAN LOW-CARBON DEVELOPMENT PATHWAYS.

A forward-looking approach to energy infrastructure development

In the past, economic development strategies in Africa have been fashioned as catching-up strategies, based on technologies and markets in industrialized economies. In the energy sector, climate change and the related transformation of energy systems around the world are rendering this development option questionable. There is currently no blueprint for an energy system that leapfrogs fossil energy carriers. Therefore, developing Africa’s energy infrastructure will need to follow a forward-looking approach, which leverages emerging international technological trends to build local, low-carbon development pathways. If embraced by African leaders and supported by the G20, such an approach may offer important opportunities for economic advancement and indigenous value creation, while avoiding the substantial risks of investing in emission intensive fossil-based energy technologies. The expansion of the electricity grid and promotion of off-grid electricity services will have to proceed hand in hand. The advantages of grid-based connectivity should be combined, where feasible and appropriate, with the benefits of decentralized energy technologies, which offer the potential to quickly and cost-effectively improve electricity access in rural areas.

Promoting energy services for climate resilience

Investments in energy infrastructure and increasing access have an important role to play in adapting to the negative effects of climate change, including extreme weather events. The impacts of heatwaves, occurring in increasing frequency and intensity, and the rise of average temperatures on human well-being, can be ameliorated by extending access to electricity and cooling systems. These will minimize negative impacts on human health and industrial processes, such as reduced thermal efficiency. In the case of drought, access to electricity is fundamental for the implementation of adaptation measures in agriculture, e.g., water management and irrigation. Increased access to energy can reduce deforestation and land degradation, e.g. by avoiding wood collection for fuel, or the use of charcoal. This can also be seen as a preventive adaptation strategy. This brief contends that increased support for clean cook stoves is a beneficial strategy.

Targeted interventions for clean cooking offer important economic and health benefits to the poorest sections of the population. They also contribute to climate change mitigation[32], adaptation and forest conservation, due to reduced use of firewood and charcoal. However, so far, most international activities that aim to tackle energy poverty on the African continent focus on improving access to electricity; improved cooking stoves still receive comparatively little attention[33]. They thus deserve increased support in the future.

RECOMMENDATION 3: LEVELING THE PLAYING FIELD FOR A LOW CARBON ENERGY TRANSFORMATION

Getting incentives right

Inefficient fossil fuel subsidies directly subsidize carbon emissions and are a major barrier for investments in sustainable infrastructure, such as renewable energy. G20 countries should support African policy makers in finding feasible and politically acceptable solutions to eventually move from negative towards positive carbon pricing and hence provide the right economic incentives for investments in clean and sustainable infrastructure.

In African countries, removing inefficient fossil fuel subsidy reforms, and – eventually – introducing carbon pricing is often found to have progressive distributional effects, i.e., the poorest sections of the population are less affected than the rich. Nevertheless, removing subsidies frequently has a negative impact on poor household incomes. To alleviate negative income effects a relatively small share of savings can be sufficient to finance adequate compensation schemes, as for example shown by Ghana[34]. Additionally, revenues can be used to close existing infrastructure gaps and finance sustainable development goals[35]. Savings from fossil fuel subsidy reforms would be sufficient to cover a substantial, important share of investments required without depending on international transfers. This would enable national resources to be mobilized as demanded in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda.

Intergrated approaches to de-risking investments in renewable energy

The scaling-up of renewable energy in Africa is currently constrained by high financing costs in the individual countries. This includes but is not limited to the unfavorable sovereign credit rating of many African countries. It reflects a number of perceived or actual informational, technical, regulatory, financial and administrative barriers and their associated investment risk[36]. Compared to fossil fuel based technologies, low-carbon technologies are more capital intensive and therefore affected by higher investment risks and financing costs[37]. In the absence of instruments to reduce capital costs of renewable energy, a first best climate policy such as carbon pricing would not be effective in triggering a low-carbon transformation in the energy system[38].

To address the existing investor risks and improve the competitiveness of renewable energy in Africa, G20 countries should support African policy makers to reduce policy risks and increasingly apply and facilitate de-risking instruments targeted at renewable energy investments. De-risking should be supported along the following strategic lines[39]:

- First, policy de-risking should address the underlying barriers to investment and support the broader enabling environment for investment in renewable energy. Instruments include, for example, support for policy design, targeted interventions to address regulatory hurdles, improving institutional capacity, etc.

- Second, financial de-risking instruments should be applied to transfer risk from private investors to public actors, where needed. A range of so-called “private sector instruments”, such as guarantees, subordinated debt or equity, is already available and should be strengthened[40]. National or multilateral development banks could employ public financing to mobilize private investments, which contribute to a declared development target.

To further bolster the use of private sector instruments in official development cooperation, the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee has made important efforts to modernize its statistical system to capture risks taken by development agencies in the deployment of private sector instruments[41]. These changes to the reporting of Official Development Assistance will provide additional incentives to donors for employing such instruments in the future. The recent developments are promising. They indicate that the portfolio of available instruments is expanding. To further increase their overall use and effectiveness, however, it will be essential to integrate these instruments within comprehensive country-level de-risking strategies. In isolation, private sector instruments are likely to remain untapped as they can only target selected risks. It is essential that such financial instruments are embedded in a multi-pronged approach aimed at developing a stable investment climate for renewable energy.

RECOMMENDATION 4: SUPPORTING SMART AND SUSTAINABLE URBAN PLANNING.

The G20 and African leaders should address the needs of the population living in slums and promote smart and sustainable urban planning; Access to basic services (water, sanitation and energy) should be extended to the peri-urban areas, the transport sector should be regulated, affordable housing and green buildings should be introduced, and industrial and service sectors should be boosted.

The further spread of clean, grid-based urban electricity services, and incentives to use modern energy sources and more efficient cooking appliances, are necessary to deal with the rise in energy demand, to improve wellbeing and contain the upsurge of urban pollution that accompanies rapid urbanization.

Investments in infrastructure and services should then to be coupled with regulation targeting the transport sector (ban of certain vehicles types and emission standards), dis-incentivizing the mobility based on fossil fuel-powered automobiles in favor of public transport, non-motorized transport and small electric vehicles. Pollution is not the only problem caused by uncontrolled development of the transport sector; economic damage connected to traffic congestion is already evident in megacities such as Bangkok and Mexico City. In addition, prioritizing the development and access to public transport is an inclusive policy that provides an adequate means of transport to people who cannot afford an automobile[42].

The high and increasing demand for affordable housing is also an opportunity for the African construction sector, which, under adequate public support and regulation, could switch towards green and more resilient building practices (energy efficiency and insulation). The development of industrial and service infrastructures is beneficial to income generation and increased wellbeing in urban areas. It is also a necessity in order to satisfy an increasing demand for goods and services.

References

- This policy brief is was lead-authored by Shingirirai S Mutanga, Rainer Quitzow and Jan Christoph Steckel but benefited considerably by the following contributing authors: Amar Bhattacharya (Brookings, Washington D.C, USA), Anna Pegels (German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE)), Clara Brandi (German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE)), Gerd Leipold (Climate Transparency), Lorenza Campagnolo (FEEM-Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei, Italy), Kamleshan Pillay (BRICS- Human Science Research Council), Martin Kaggwa (SATRI-Sam Tambani Research Institute, South Africa), Sybille Röhrkasten (IASS-Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies, Potsdam), Thokozani Simelane (HSRC-Human Science Research Council, South Africa)

- Niang, I., O.C. Ruppel, M.A. Abdrabo, A. Essel, C. Lennard, J. Padgham, and P. Urquhart, 2014: Africa. In: Climate Change (2014): Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Barros, V.R., C.B. Field, D.J. Dokken, M.D. Mastrandrea, K.J. Mach, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea, and L.L.White (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1199-1265.

- Lyndsey Duff (2011): Overcoming barriers to climate change adaptation implementation in Southern Africa. AISA, South Africa.

- Alison Doig and Mohamed Adow, Christian Aid (2011): Low-carbon Africa: leapfrogging to a green future. Christian Aid

More Information - Schwerhoff, G. Sy Mouhamadou, (2016): Financing renewable energy in Africa – Key challenge of the sustainable development goals. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews.

- Mutanga, S, Simelane T, Pophiwa N. (2013): Africa in a global environment change. Perspectives of climate change adaptation and mitigation Strategies in Africa. AISA, South Africa.

- Simelane T and Abdel Rahman Energy Transition in Africa. AISA, South Africa.

- World Bank (2015): Decarbonizing Development. World Bank, Washington, DC.

- WEO 2016. Electricity Access database.

Accessed Online. - Energy for a Sustainable Future, the SecretaryGeneral’s Advisory Group On Energy And Climate Change (AGECC):

Summary Report and Recommendations, UNDP, 28 April 2010, - Alstone, P., Gershenson, D., & Kammen, D. M. (2015). Decentralized energy systems for clean electricity access. Nature Climate Change, 5(4), 305-314 and literature cited therein.

- Peters, J., & Sievert, M. (2016). Impacts of rural electrification revisited–the African context. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 8(3), 327-345.

- Pachauri, S., van Ruijven, B. J., Nagai, Y., Riahi, K., van Vuuren, D. P., Brew-Hammond, A., & Nakicenovic, N. (2013). Pathways to achieve universal household access to modern energy by 2030. Environmental Research Letters, 8(2), 024015.

- Rao, N.D., S. Pachauri (in press): Energy access and living standards: Some observations on recent trends. Environmental Research Letters.

- Pachauri, S., van Ruijven, B. J., Nagai, Y., Riahi, K., van Vuuren, D. P., Brew-Hammond, A., & Nakicenovic, N. (2013).

- Csereklyei, Zsuzsanna, and David I Stern. (2015): “Global Energy Use: Decoupling or Convergence?” Energy Economics 51: 633–41.

- Jakob, Michael, Markus Haller, and Robert Marschinski. (2012): “Will History Repeat Itself? Economic Convergence and Convergence in Energy Use Patterns.” Energy Economics 34 (1): 95–104.

- Steckel, J. C., Brecha, R. J., Jakob, M., Strefler, J., & Luderer, G. (2013): Development without energy? Assessing future scenarios of energy consumption in developing countries. Ecological Economics, 90, 53-67.

- Lee, K., Miguel, E., & Wolfram, C. (2016). Appliance ownership and aspirations among electric grid and home solar households in rural Kenya. The American Economic Review, 106(5), 89-94.

- Steckel JC, Edenhofer O, Jakob M. (2015): Drivers for the renaissance of coal. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; 112 (29):E3775–E3781.

- Shearer, Christine, Nicole Ghio, Lauri Myllyvirta, Aiqun Yu, and Ted Nace. (2016): “Boom and Bust 2015. Tracking the Global Coal Plant Pipeline.” CoalSwarm, Greenpeace and Sierra Club.

More Information - Steckel, JC, J Hilaire, M Jakob, O Edenhofer (2017): Lions in the dragon’s shoes? On carbonization patterns in Sub-Sahara Africa. MCC Working Paper.

- Lucas, Paul L., Jens Nielsen, Katherine Calvin, David L. McCollum, Giacomo Marangoni, Jessica Strefler, Bob C.C. van der Zwaan, and Detlef P. van Vuuren. 2015. “Future Energy System Challenges for Africa: Insights from Integrated Assessment Models.” Energy Policy 86 (November): 705–17. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2015.08.017.

- Calvin, Katherine, Shonali Pachauri, Enrica De Cian, and Ioanna Mouratiadou. (2016): “The Effect of African Growth on Future Global Energy, Emissions, and Regional Development.” Climatic Change 136 (1): 109–125. doi:10.1007/s10584-013-0964-4

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2014). World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision, Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/352).

- Habitat III (2015): Informal settlements. Habitat III Issue Papers, New York, N.Y.:

- Creutzig, F., Agoston, P., Minx, J. C., Canadell, J. G., Andrew, R. M., Le Quéré, C., … & Dhakal, S. (2016). Urban infrastructure choices structure climate solutions. Nature Climate Change, 6(12), 1054-1056.

- d’Amour, C. B., Reitsma, F., Baiocchi, G., Barthel, S., Güneralp, B., Erb, K. H., … & Seto, K. C. (2016). Future urban land expansion and implications for global croplands. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 201606036.

- UNDP 2010. Energy for a Sustainable Future, the Secretary General’s Advisory Group On Energy And Climate Change (AGECC)

Summary Report and Recommendations, UNDP, 28 April 2010, - Speech by Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble, German Federal Minister of Finance, at the B20 Conference on 1 December 2016 in Berlin

More Information - Rainer Quitzow, Sybille Röhrkasten, Marit Berchner, Boris Gotchev, Patrick Matschoss, Jan Peuckert (2016): Mapping of Energy Initiatives and Progams in Africa. Report prepared for the Africa-EU Energy Partnership

More Information - Shindell, D. et al. (2012): Simultaneously Mitigating Near Term Climate Change and Improving Human Health and Food Security. Science 335, 183 (1) 89.

- Quitzow, R., Röhrkasten, S., Jacobs, D., Bayer, B., Jamea, E. M., Waweru, Y., Matschoss, P. (2016): The Future of Africa’s Energy Supply. Potentials and Development Options for Renewable Energy. – IASS Study, March 2016.

- Lindebjerg, E. S., Peng, W., & Yeboah, S. (2015). Do policies for phasing out fossil fuel subsidies deliver what they promise? Social gains and repercussions in Iran, Indonesia and Ghana (No. 2015-1). UNRISD Working Paper.

- Jakob, M., Chen, C., Fuss, S., Marxen, A., & Edenhofer, O. (2015). Development incentives for fossil fuel subsidy reform. Nature Climate Change, 5(8), 709-712.

- Waissbein, O., Glemarec, Y., Bayraktar, H., & Schmidt, T.S., (2013). Derisking Renewable Energy Investment. A Framework to Support Policymakers in Selecting Public Instruments to Promote Renewable Energy Investment in Developing Countries. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme.

Available online [Accessed February 2017] - Schmidt, T. S. (2014). Low-carbon investment risks and de-risking. Nature Climate Change, 4(4), 237-239.

- Hirth, L., & Steckel, J. C. (2016). The role of capital costs in decarbonizing the electricity sector. Environmental Research Letters, 11(11), 114010.

- Waissbein, O., Glemarec, Y., Bayraktar, H., & Schmidt, T.S., (2013). Derisking Renewable Energy Investment. A Framework to Support Policymakers in Selecting Public Instruments to Promote Renewable Energy Investment in Developing Countries. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme.

Available online [Accessed February 2017] - https://www.cicero.uio.no/en/posts/selected-publications/instruments-to-incentivize-private-climate-finance-for-developing-countries.

More Information - OECD (2016): DAC High Level Meeting Communiqué. February 19, 2016, Paris: OECD.

- UNCTAD (2015), Science, Technology and Innovation for Sustainable Urbanization, UNCTAD Current Studies on Science, Technology and Innovation, No 10.