In order to preserve the central role of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in global trade it is necessary to revive the negotiating function of the organization. Plurilateral cooperation can be a stepping stone towards closer integration on issues where multilateral consensus is not yet in sight. However, a closer analysis of older and current plurilaterals reveals that they are largely initiated by developed countries and are not a generally accepted negotiation method for all WTO members. This policy brief analyses plurilaterals on grounds of key criteria such as treatment of non-members, scope and membership. It then clarifies the key challenges of using plurilaterals as a negotiation approach to advance new sets of rules. The brief provides G20 and WTO members with a set of practical recommendations for the successful operation and conduct of plurilaterals to support a multilateral order that serves the interests of all members and, in particular, those of developing countries.

Challenge

In view of the need to modernize the World Trade Organization (WTO), including its outdated rule book, sub-groups of members are increasingly interested in plurilateral initiatives.1 While plurilaterals are almost as old as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the WTO’s predecessor, in recent years members have become increasingly interested in plurilaterals on issues ranging from e-commerce, investment facilitation, services, trade and sustainability to trade and health issues. For many members, plurilateral negotiations represent a way to revitalize multilateralism and to negotiate new rules and market access opportunities.

However, plurilaterals are contested by some WTO members, including G20 countries. Recently, India and South Africa argued that plurilaterals are not consistent with WTO rules as long as they are not agreed consensually (WTO, 2021). This argument was questioned by, inter alia, the European Commission (2021, pp. 11f.), emphasizing that plurilaterals do not violate multilateralism if they are open to new members and negotiated on a most-favoured-nations (MFN) basis (Lewis, 2021). Furthermore, there is a danger that objecting to plurilaterals as legitimate WTO instruments may increase the tendency to conclude agreements outside the multilateral framework with negative consequences for the credibility of the WTO.

Plurilaterals can be a stepping stone towards closer multilateral integration on issues where consensus is not yet in sight: the plurilateral approach can thus provide an opportunity to further liberalize trade and bring in new rules, and it should not be refuted by a priori decision. Yet the evidence indicates that plurilaterals are largely initiated by advanced economies, while developing countries are less willing, or in fact less equipped, to participate. If the WTO is to be sustainably modernized, a goal we strongly support, it must find ways to accommodate diverse member interests, notably those of developing countries.

Currently, a number of plurilaterals are negotiated in parallel with insufficient coordination, increasing the risk of creating duplicating or even contradictory commitments and putting further strain on developing countries’ scarce negotiation capacities. Moreover, procedural criteria for the launch and conduct of plurilateral negotiations are lacking, and the inclusion of ensuing agreements in the WTO rule book is contested.

A more structured and institutionalized approach to plurilateral negotiations could therefore enhance the potential for updating the WTO’s rule book and, thus, for reforming the organization as argued in a previous T20 policy brief (Berger et al., 2020): the G20 should assume a key role in incentivizing discussions and dialogue on the use of plurilaterals, without questioning the centrality of the WTO as the key decision-making forum for institutional reforms. To enable informed discussions among G20 as well as WTO members, we first succinctly document the state of play in the individual plurilateral tracks, before identifying common as well as specific challenges. Based on this analysis, we suggest institutional arrangements for the initiation of plurilateral negotiations including the identification of issue areas, the conduct of inclusive and transparent negotiations vis-à-vis non-participants and the public, and the incorporation of an agreement into the WTO framework.

Proposal

TAKING STOCK

Plurilaterals do not follow a one-size-fits-all approach. Rather, several plurilaterals negotiated since the 1980s have followed different models, depending on the purpose they served at a given time in the evolution of the multilateral trading system. We apply three key criteria to underline the diversity of plurilateral approaches, namely, treatment of non-signatories, scope and membership.

Treatment of non-signatories: inclusive versus exclusive plurilaterals

Plurilaterals can be classified into two types of agreements: inclusive plurilaterals, meaning their provisions are available to all WTO members, and exclusive plurilaterals, wherein the benefits are available only to members.2 In principle, inclusive plurilaterals can be negotiated by subsets of the membership, provided they do not erect additional barriers to non-participants and that they make the benefits of their negotiations available on an MFN basis. Importantly, this covers both traditional market access agreements and agreements on new rules. Exclusive arrangements will alter the existing balance of concessions for participants only, and for this reason they must be adopted by all members through consensus. Specifically, Article X:9 of the WTO agreement provides that “the Ministerial Conference … may decide exclusively by consensus to add that agreement to Annex 4”.

Scope: three phases of plurilateral negotiations

The first plurilateral agreements under the GATT and the (early) WTO include the Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) (1981, subsequently updated), the Pharma Agreement (1994), the Information Technology Agreement (ITA) (1996, subsequently updated), the GATS Telecoms Reference Paper (1998) and the GATS Finance Reference Paper (1999).3 All five are market access agreements which take a positive list approach to the respective commitments, but they take different approaches to the extension of benefits to non-signatories:

- The Government Procurement Agreement comprises individual commitments regarding procuring entities, as well as the goods and services which are open to foreign competition. In addition, the GPA establishes rules for open, fair and transparent conditions of competition in government procurement. The commitments of the GPA are applied on a non-MFN basis.

- The Agreement on Trade in Pharmaceutical Products (the Pharma Agreement) eliminates tariffs, other duties and charges on several pharmaceutical products. Parties implement it on an MFN basis.

- The Information Technology Agreement covers a large number of high-technology products, which are traded tariff free on an MFN basis.

- The Telecoms Reference Paper lists a set of regulatory principles for members to adopt in their schedules of basic telecommunications commitments. The Annex legally forms part of the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) and commitments are applied on an MFN basis.

- The Finance Reference Paper is included in the GATS as an Annex on Financial Services. In addition, there is an Understanding on Commitments in Financial Services, which is not appended to the GATS. Both are applied by parties on an MFN basis.

In the second phase, two additional plurilaterals were launched during the deadlocked Doha Round. Negotiations on the Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) were started in March 2013. Its status was never clarified since the talks took place outside the WTO with the option of becoming a regional trade agreement (RTA) under GATS Article 5. The TiSA negotiations combined specific market access commitments in services as well as horizontal rules (e.g. for transparency, domestic regulation).

The negotiation towards an Environmental Goods Agreement (EGA) was launched in July 2014 and framed as an inclusive MFN market access agreement. The EGA tried to define the liberalization of trade in specific environmental products, applying a similar structure and scope to the ITA. Both the TiSA and EGA negotiations stalled in 2016.

In the third phase, four Joint Statement Initiatives (JSIs) were initiated in December 2017 at the 11th WTO Ministerial Conference in Buenos Aires, building partly on previous mandates and processes. They vary in scope and level of ambition:

- The e-commerce negotiations focus on new rules in this area and potential market access commitments. They cover the extension of the WTO Moratorium on Customs Duties on Electronic Transmissions, measures to facilitate electronic transactions including data flows and to discipline data localization, net neutrality, and enhancing market access in goods and services.

- The negotiations on services domestic regulation and investment facilitation for development aim to improve existing administrative procedures and frameworks for services and investment. The aim particularly for services domestic regulation is for parties to inscribe commitments into their respective GATS schedules of commitments. This approach has limited applicability in the case of the investment facilitation for development agreement as it also covers investments in non-services sectors, which are not covered by the GATS (Adlung, Sauvé and Stephenson, 2020).

- The least ambitious JSI relates to micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs). It was intended as a reflection process among a group of members on how to help MSMEs to integrate into global value chains. An informal Working Group open to all WTO members was launched to identify and address obstacles to MSME participation in international trade.

Most recently, the Structured Discussions on Trade and Environmental Sustainability (TESSD) were started in November 2020. So far, the scope of the discussions is undefined, but the work programme will likely focus on increased market access for environmental goods and services, with a potential focus on the circular economy. At a meeting on 5 March 2021, TESSD participants submitted nine proposals outlining future priorities for the structured discussions. The meeting did not resolve the differences among members over whether to focus on a negotiating agenda or on exploratory work.

Similarly, the Ottawa Group, consisting of thirteen WTO members supporting WTO reforms, proposed a Global Trade and Health initiative that aims to permanently eliminate tariffs on essential medical goods. This plurilateral initiative so far focuses on market access (though there are discussions to include development concerns) and will probably be designed in the same way as the ITA or the EGA.

Membership

Plurilaterals provide a framework for sub-groups of like-minded WTO members to advance negotiations on specific issues in which they are particularly interested. On average only 40 per cent of WTO members are participating in the plurilateral agreements and negotiations covered in this brief. This overall figure, however, hides important variations. Firstly, the plurilateral agreements and negotiations differ significantly in terms of the involvement of developing countries (Annex, Figure 1). Secondly, high-income countries are the key participants in most plurilateral agreements and negotiations (Annex, Figure 2). Thirdly, participants in plurilaterals are often the key trading nations. Moreover, it is noticeable that the willingness, or ability, to engage in plurilateral negotiations significantly decreases with members’ level of development (Annex, Figure 3). In the case of G20 members, three groups can be identified: a pro-plurilateral group mainly composed of advanced economies; an unwilling group, that is, India, South Africa and Indonesia; and the waverers such as Argentina, Brazil, China, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia and the USA, whose participation is more conditional.

KEY QUESTIONS ON THE WTO COMPATIBILITY OF PLURILATERALS

Is achieving critical mass essential?

The chances that an agreement will be accepted by non-participants will be higher in the case of inclusive plurilaterals that are open to new members and extend MFN treatment to non-signatories. Nevertheless, difficulties exist. Inclusive agreements are prone to free-riding as non-members are allowed to benefit from MFN coverage while not being obligated to provide reciprocal concessions. To reduce this risk, a higher participation threshold can be sought, including members representing a considerable share of trade in the area concerned, creating large benefits through the agreement to compensate for the cost of free-riding, or critical mass (though not defined formally). However, the larger the group, the more complex it can be to reach meaningful outcomes. Furthermore, the need to reach a critical mass may not be necessary in the case of plurilaterals focusing on regulatory reforms as they are often horizontal in nature, thus applying to all trading partners, and they are beneficial mainly for the countries that implement them and therefore do not lend themselves to trading of reciprocal concessions.

Convincing developing members that plurilaterals are beneficial

Many developing countries, including some G20 members, refrain from taking part in plurilateral initiatives (Figures 1 and 3 in the Annex). Two issues can explain their unwillingness:

firstly, they may not trust that plurilaterals are a useful forum in which to pursue their interests. This is largely in contrast to the consensus-based approach of multilateral negotiations, wherein they can prevent an outcome if they determine that their cost-benefit equation is distorted. Many developing countries worry that plurilateral negotiations will be guided by the interests of major trading parties, imposing conditions and new standards that they will be obliged to implement (Draper and Dube, 2013, pp. 1-2). Many even have concerns about open, non-discriminatory plurilaterals, because when they join at a later stage, they may have to comply with policies already adopted by the members of the plurilateral (Hoekman and Sabel, 2019, p. 55).

Secondly, developing countries’ reluctance can be related to technical capacity problems. Many trade agreements push countries to change their domestic rules for adopting new liberalization commitments and internationally agreed rules. This requires robust adjustment mechanisms and technical capacities for the transformation process. Hence, plurilaterals need to consider developmental aspects to solve the capacity problem of developing countries.

Are plurilaterals fragmenting the WTO?

Another concern is that the WTO rule book may be fragmented both legally and politically if plurilaterals lead the system towards a “differentiated structure” even if their legitimacy is assured under WTO rules. Hoekman and Mavroidis (2015, p. 334) argue that claims that plurilateral approaches may result in a two-track regime that splits “insiders” from “outsiders” must be considered in relation to the substantive content of the deal and the intention of the countries that agreed to negotiate. Most plurilateral negotiations aim at MFN commitments, which substantially eases worries about splitting the membership. Moreover, if a plurilateral route is denied for strategic or other reasons based on the consensus rule, the alternative could be their migration to venues outside the WTO sphere, putting further pressure on non-signatories and the multilateral system.

As the Sutherland Report pointed out long ago, the need for a consensus amongst all WTO members to add a plurilateral agreement to the WTO treaty must be revisited. Moreover, as Pauwelyn (2005, p. 343) argues, “although some control by the entire WTO membership over new agreements is useful (e.g. to make sure that plurilateral agreements do not harm the rights of third parties), a single member ought not have a veto to block the progress in the WTO”.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The informality of the G20 provides an opportunity to exchange views, establish trust and possibly find common ground on plurilaterals. However, the G20 can only provide an informal platform for dialogue, while reforms need to be negotiated and adopted at the level of the WTO.

To enhance discussion on plurilaterals within the G20, we suggest the Italian presidency establishes a sub-committee under the G20 Trade and Investment Working Group (TIWG) to

initiate and lead discussions on the usage and reform of plurilateral negotiations within the WTO. The sub-committee would bring together G20 members and relevant international organizations but would also be free to invite leading experts to provide consultation on alternative negotiating modalities, mainly on plurilateral negotiations. The sub-committee could also discuss a code of conduct to govern the initiation, negotiation and implementation of plurilaterals. The sub-committee should complete its work prior to the conclusion of the forthcoming Indonesian presidency.

As part of the sub-committee’s deliberations, the G20 should also reflect on new plurilateral initiatives that are in the interest of the broader membership. Discussions towards an agreement on essential health and food products should be the first step. Such plurilateral negotiations could focus on the liberalization of trade in essential health products (i.e. medicines and vaccines) and services as well as the reduction of food export barriers, in line with guidelines as agreed and adopted at the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis by G20 Trade and Investment Ministers on 30 March 2020 and Agriculture Ministers on 21 April 2020. Such negotiations would be a strong signal that the multilateral trading system works to reduce human suffering.

This brief proposes the following practical recommendations for the negotiation of inclusive plurilateral agreements.4 These recommendations are mainly addressed to WTO members in Geneva but could also inspire discussions within the TIWG.

Focus on development aspects is key for the negotiation of inclusive plurilaterals

It is key to increase developing countries’ capacities to negotiate and implement the outcomes. To enhance their capacities, it would be useful to expand existing funds sourced from developed and developing country members in a position to do so to support developing country officials from Geneva-based missions and capitals especially to participate effectively in the negotiations.

In addition, the approach towards Special and Differential Treatment (SDT) applied in the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) offers a useful model to account for developing countries’ specific challenges, in particular regarding the implementation of plurilateral commitments. In the TFA, SDT did not grant broad exemptions or long transition periods, rather it includes tailored (to developing countries’ capacities) differentiations within the agreement tied to technical assistance. The TFA features a tailor-made approach for the implementation of specific measures and policy areas.

Avoid negative effects for outsiders

Members of plurilateral agreements need to make sure that countries that are not part of the agreement are not negatively affected. To achieve this, negotiations need to be open at all stages to new members. The negotiations chair also needs to reach out to non-members (particularly developing countries) to address their concerns and to remove possible hurdles for participation. Accession of new members should not be on more stringent terms than those applied to incumbents.

Clarify the legal status of plurilaterals

The current plurilaterals under the JSIs are being negotiated without clarifying the procedures of their eventual incorporation into the WTO system. A legal clarification is essential to counter a priori arguments suggesting their incompatibility with WTO laws. Whether Article X:9 should be applied to JSIs and other possible plurilaterals in the future agreement is open to discussion. An independent expert group could be established by the WTO’s General Council for consultative purposes, while the G20 TIWG sub-committee should also discuss it.

Avoid substantial overlaps in the different agreements

There is overlap of the issues being discussed in the JSIs, in particular on services domestic regulation and investment facilitation for development. Many of the underlying issues are very similar, for example on transparency requirements, predictability of application processes and efficiency of regulatory processes. There is also substantial overlap with existing WTO agreements, in particular the GATS (Adlung, Sauvé and Stephenson, 2020). As there is no coordinated approach to the JSIs, this poses the danger of creating overlapping and, in the worst case, divergent and non-compatible rules of different plurilateral agreements as well as existing WTO agreements.

To avoid this situation, it is important not only to increase coordination on the launch of new plurilaterals, ideally on the basis of a given set of criteria to be developed by the TIWG, but also to have established coordination meetings among the chairs of the different plurilateral tracks. It is also necessary to strengthen the role of the WTO Secretariat to better support the individual plurilateral initiatives. To this end, the Secretariat should be empowered to establish a mechanism for technically evaluating new initiatives regarding possible issue overlaps to avoid a spaghetti bowl of provisions.

Conduct ex ante impact assessments and ex post evaluations on plurilaterals

The WTO Secretariat in cooperation with the relevant international organizations should be empowered to conduct ex ante impact assessments on the benefits and challenges of plurilaterals for negotiating participants and for the broader WTO membership. It is important for WTO members, and particularly for developing countries, to know about the potential risks and benefits prior to joining the negotiations. These impact assessments therefore need to be conducted at a very early stage, ideally before the start of formal negotiations. In addition, it is useful to evaluate past plurilateral initiatives and draw lessons from them for future negotiations. An annual report assessing the implications of plurilateral agreements could be prepared by the WTO Secretariat.

Increase transparency, including for the general public, to establish trust

Given the controversial nature of plurilaterals, negotiating members should increase transparency regarding the procedural and substantive aspects of negotiations. This relates not only to the members of the agreement and the broader WTO membership, but also to the general public. This is essential for creating trust among WTO members and the public regarding the different plurilateral approaches. Non-participating countries need to be reassured by providing with information about every plurilateral agreement regarding its operation and implementation.

Continue with additional online negotiations to help ease capacity problems

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many negotiations have had to be conducted online. This new way of negotiating has advantages, which could also be applied in post-pandemic times. Even though it is important to meet in person, the additional option to negotiate online for example in the case of intersessional meetings or stakeholder meetings could help address capacity problems of developing countries. Crucially, online negotiations can allow government officials from capitals with in-depth, technical knowledge to participate more actively, freeing up capacities in the missions in Geneva, and they can help to engage early on those actors who will be responsible later for the implementation of new commitments.

ANNEX

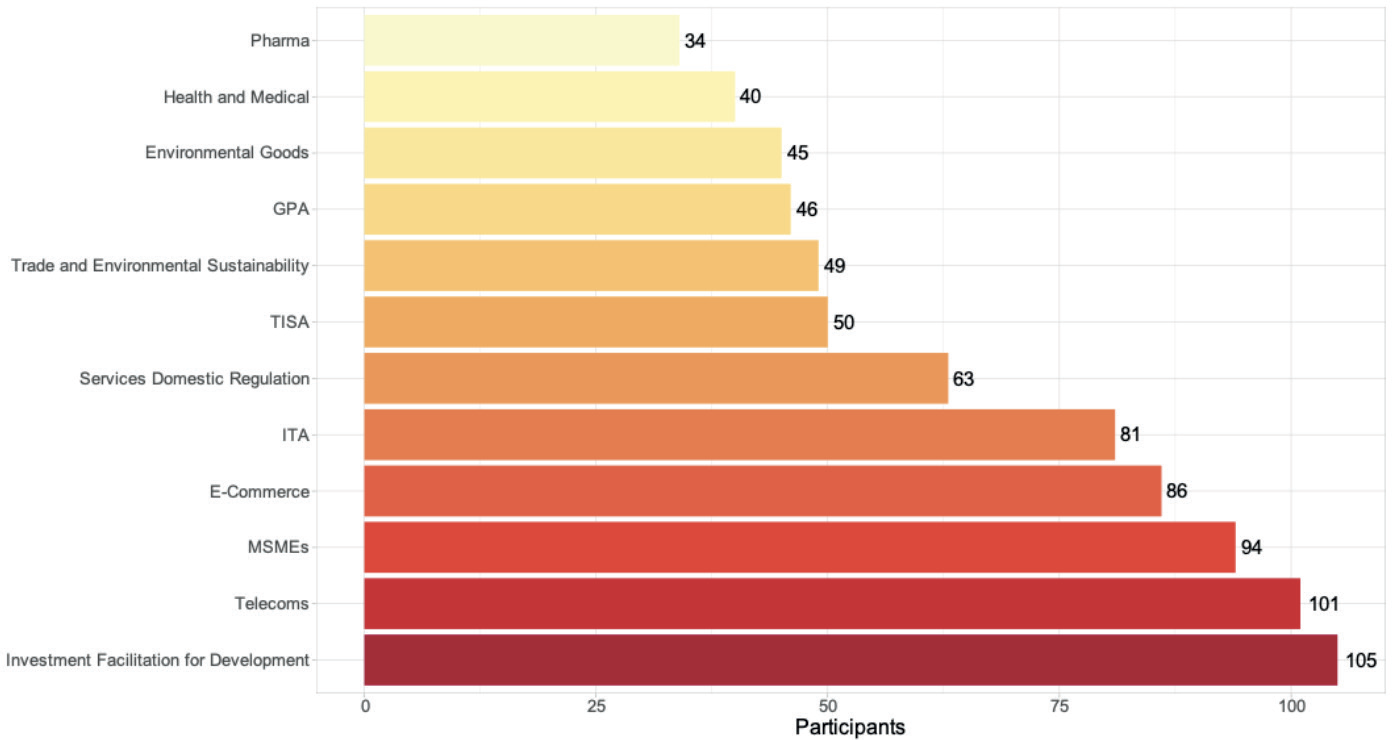

The annex gives an overview of memberships in plurilateral negotiations. The first notable feature is that the number of members varies. Among the ongoing negotiations, the Investment Facilitation for Development negotiations are the most inclusive plurilateral with 105 members participating. Among the existing plurilateral agreements, the Telecoms Reference paper has the highest membership with 101. At the other end of the spectrum, the current Pharma negotiations and the GPA have only thirty-four and forty-six members respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Number of participating members per plurilateral

Source: Authors, based on information made available by the WTO, see: www.wto.org

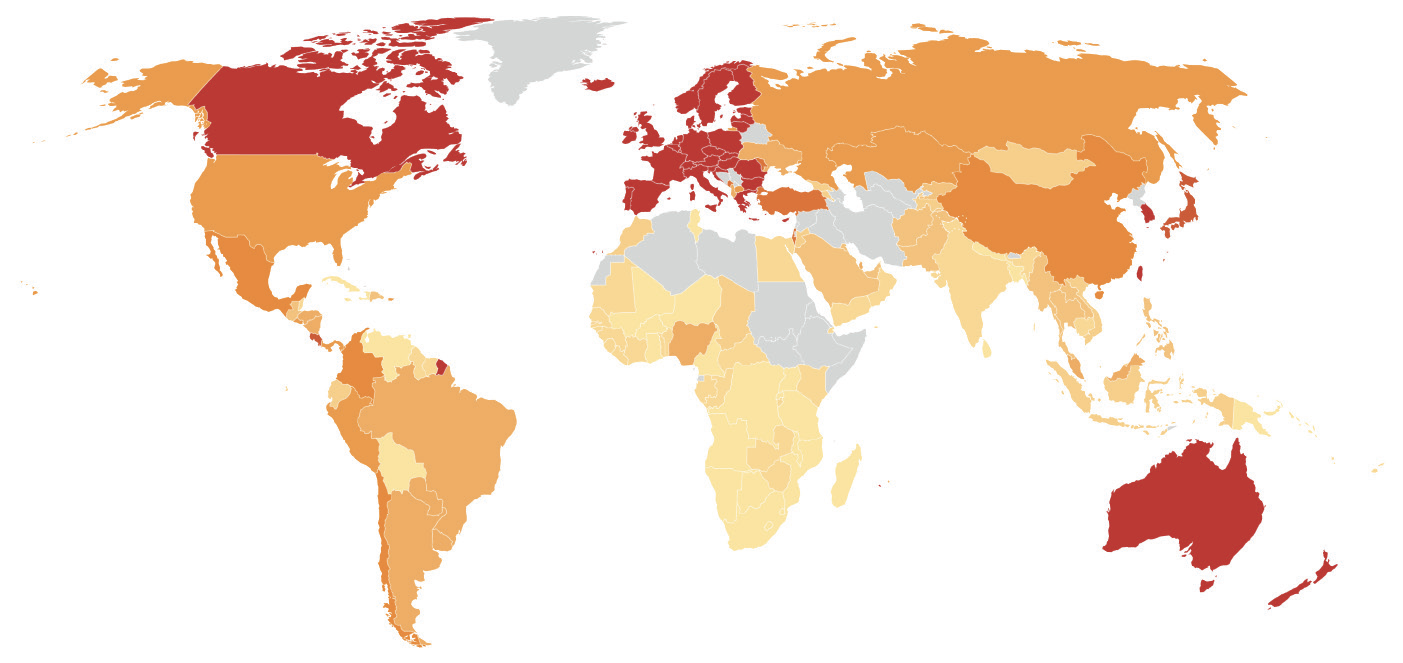

Figure 2: Participation in plurilateral agreements and ongoing negotiations per member

Source: Authors, based on information made available by the WTO, see: www.wto.org

Furthermore, it is important to note that in most plurilateral agreements and negotiations high-income countries are the key participants. Figure 2 shows that a handful of members, including Canada, the European Union, Switzerland, Norway and Australia, are signatories of all existing plurilateral agreements or participants in all ongoing negotiations. Costa Rica and Japan are participating in eight plurilaterals. Then there is a group of members, comprising the USA, Mexico, Colombia, Turkey and China, which are participating in five to seven plurilaterals. Many Latin American and South and South-East Asian countries are participating in four or fewer plurilaterals. A number of developing country members, in particular on the African continent, are not participating in any of the plurilaterals.

The members that are participating in plurilaterals are often key trading nations. It is therefore not surprising that plurilaterals cover significant shares of world trade. The current e-commerce negotiations cover close to 93 per cent of total trade flows (91 per cent of services trade). The ITA and the Telecoms Reference Paper also cover more than 90 per cent of total trade (95 per cent of services trade). The participants in the Investment Facilitation for Development negotiations and MSMEs discussions cover more than 80 per cent of total trade (75 per cent of services trade), and the participants in both the Services Domestic Regulations and Environmental Goods negotiations cover more than 75 per cent of total trade (69 per cent and 81 per cent of services trade, respectively). The members of the GPA cover slightly more than 60 per cent of total trade (76 per cent of services trade), and the participants in the Trade and Environmental Sustainability, Pharma and Health and Medical cover only around 50 per cent of total trade (56 per cent, 66 per cent and 59 per cent of services trade, respectively).

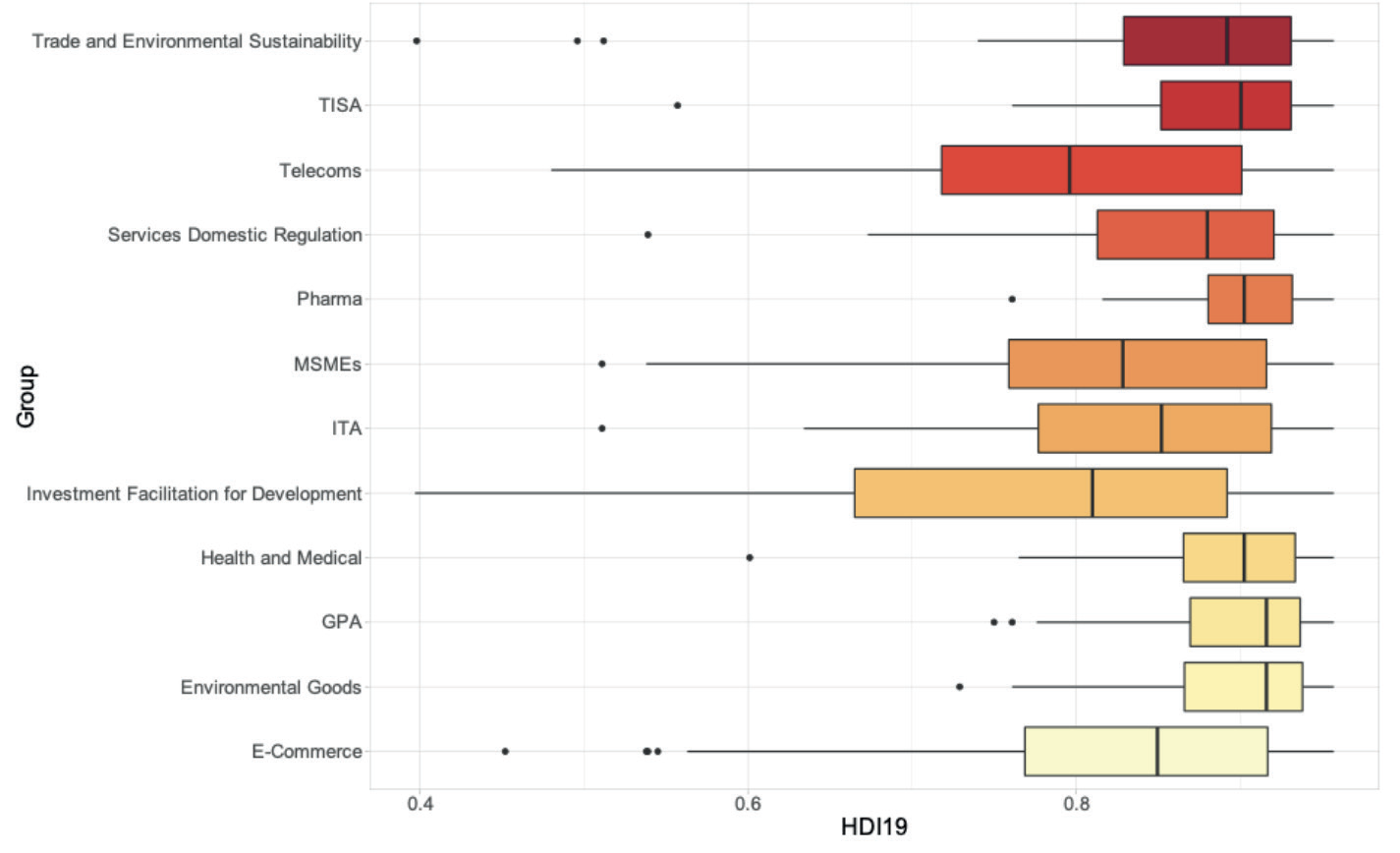

Figure 3: Distribution of members according to their HDI across plurilaterals

Source: Authors, based on information made available by the WTO, see: www.wto.org.

Moreover, it is noticeable that the willingness, or ability, to engage in plurilateral negotiations significantly decreases with members’ level of development. This relationship is displayed in Figure 3, which shows the distribution of participating members according to their level of development, measured according to the Human Development Indices (HDI), in the different plurilateral agreements and negotiation rounds. The boxplot makes clear that there is a large concentration of members with high HDI in all negotiations, and only a few of them include a larger number of less developed economies. The plurilateral initiative that includes most members with relatively low HDIs is the Investment Facilitation for Development negotiation.5

Table 1: G20 Members in Plurilateral Initiatives/Agreements

Source: Authors, based on information made available by the WTO, see: www.wto.org

NOTES

1 For useful comments on previous versions of the paper, we would like to thank Jane Drake-Brockman. We would also like to thank Florian Gitt for his excellent research assistance.

2 Following Draper and Dube (2013, p. 2). The terms inclusive and exclusive are respectively

used to refer to open and closed plurilaterals in the literature.

3 It should also be noted that the Agreement on Trade in Civil Aircraft (1979), as subsequently modified, rectified and amended, is also annexed (under Annex 4) to the WTO Agreement. The International Dairy Agreement and International Bovine Meat Agreement (under Annex 4) were terminated at the end of 1997.

4 See also Berger et al. (2020).

5 It is interesting to note that the Services Domestic Regulation negotiations, which are characterised by a strong subject matter overlap with the Investment Facilitation for Development negotiations, include much less countries (many fewer economies?) with low HDIs.

REFERENCES

Adlung R, Sauvé P, Stephenson S (2020). Investment Facilitation for Development – A WTO/GATS Perspective, in: Investment Facilitation for Development: A toolkit for policymakers, edited by A Berger and K Sauvant. Geneva: International Trade Cen tre. https://www.intracen.org/uploadedFiles/intracenorg/Content/Publications/Investment%20Facilitation%20for%20Development_rev.Low-res.pdf, accessed 22 July 2021

Berger A, Brandi C, Elsig M, Hoda A, Tu X (2020). Improving key functions of the world trade organization: Fostering open pluri laterals, regime management, and decision-making. T20 Policy Brief. https://www.g20-insights.org/policy_briefs/improving-key-functions-of-the-world-trade-organization-fostering-open-plurilaterals-regime-management-and-decision-making/, accessed 22 July 2021

Draper P, Dube M (2013). Plurilaterals and the multilateral trading system, the E15 initiative-strengthening the global trade system. ICSTD and WEF, Geneva. https://e15initiative.org/publications/plurilaterals-and-the-multilateral-trading-system/, accessed 22 July 2021

European Commission (2021). Trade policy review: An open, sustainable and assertive trade policy. https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2021/february/tradoc_159428.pdf, accessed 22 July 2021

Hoekman B, Mavroidis P (2015). WTO ‘à la carte’ or ‘menu du jour’? Assessing the case for more plurilateral agreements. The European Journal of International Law, 26(2):319-343

Hoekman B, Sabel C (2019). Open plurilateral agreements, international regulatory cooperation and the WTO. Global Policy, 10(3):297-312

Lewis MK (2021). The origins of plurilateralism in international trade law. Journal of World Investment & Trade, 20(5): 633-653

Pauwelyn J (2005). The Sutherland report: A missed opportunity for genuine debate on trade, globalization and reforming the WTO. Journal of International Economic Law, 8(2):329-346

WTO (World Trade Organization) (2021). The legal status of ‘joint statement initiatives’ and their negotiated outcomes. WT/ GC/W/819, Geneva: WTO WT/GC/W/819, 19 February. Available at https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/WT/GC/W819.pdf&Open=True