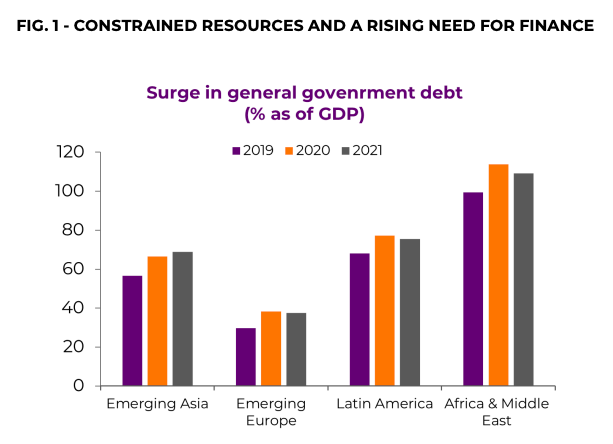

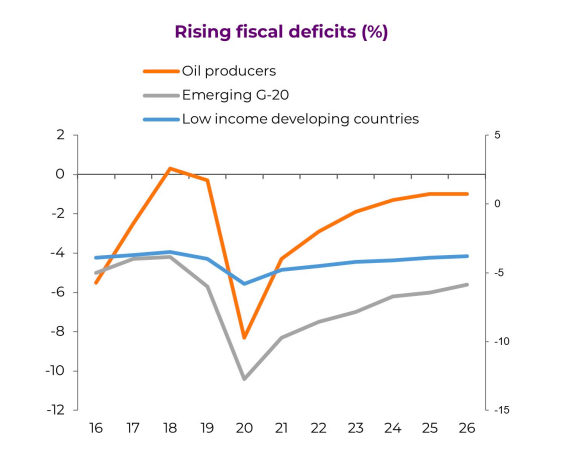

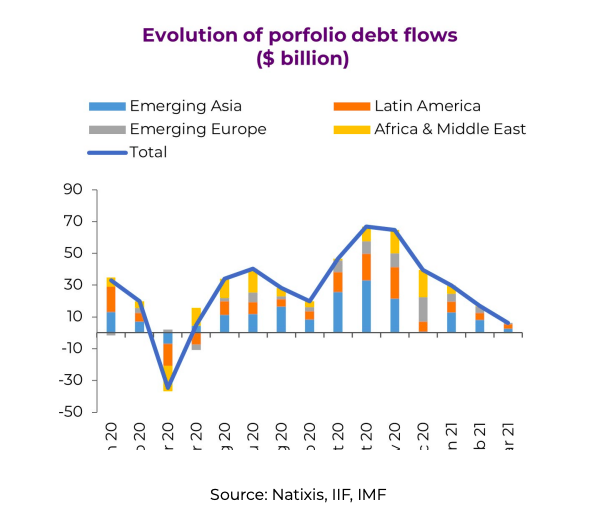

Throughout 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic caused massive human and economic casualties. The pandemic has been a major blow for developing countries, especially low-income countries, from many perspectives. These countries experienced a sudden dry-up of external financing in March 2020, against the backdrop of a rapid pile-up of sovereign debt during the last few years, coupled with a surging need for finance to combat the public health crisis (Figure 1). In this context, the international community tried to mobilise financial resources as quickly as possible to ease liquidity constraints facing these countries. Alongside exceptionally quick financial assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), the G20 countries agreed on a temporary debt moratorium in April 2020, the so-called G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI). This initiative has allowed eligible countries to delay debt-service-related payments owed to bilateral official creditors. Since its inception, it has been extended twice and it should now expire in December 2021.1

In addition, the anticipated reflation cycle in the United States led to an increase in US Treasury yields in March. The prospect of tightening global financing conditions could slow down capital flows into the emerging world or even lead to capital reversals. Moreover, the slow vaccine rollout in the emerging world and the renewed lockdowns in some of those economies may also disrupt economic recovery. Against this backdrop, emerging and developing countries need to swiftly address a two-pronged policy objective: sovereign debt sustainability and being able to fund investment, especially investment with high economic and social returns. So far, the international community – through the G20 in particular – has alleviated the liquidity strain facing developing countries with the DSSI and a quick mobilisation of financial resources by the Bretton Woods institutions. With the DSSI coming to an end in 2021 and the scepticism about the readiness of the Common Framework for Debt Treatment, additional and holistic solutions need to be developed. Otherwise, not only will a handful of low-income countries face liquidity constraints or even solvency challenges, but such circumstances could also quickly extend to middle-income countries. This is even more likely if the cost of funding were to shoot up amid looming concerns about a taper tantrum 2.0. Besides problems with new financing, solidarity and continuous efforts are needed from different creditors – multilateral institutions, public sector and private sector creditors –to deal with the legacy of the high stock of debt accumulated.

With both new financing and legacy debt issues in mind, we put forward a proposal of setting up a World Recovery Fund (WRF), aimed at addressing some of the key problems with the design of the DSSI and more generally the existing international financial architecture for dealing with debt problems in the developing world. We first describe the main challenges in the international financial architecture for post-pandemic sovereign financing, and then detail our proposal for the WRF.

Challenge

FOUR CHALLENGES IN THE INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL ARCHITECTURE FOR POST-PANDEMIC SOVEREIGN FINANCING

Prior to the global pandemic, numerous attempts were made to strengthen global liquidity provision during crisis times and improve sovereign debt restructuring processes. The outbreak of the Covid crisis has shown once again the interlinkages between sovereign debt restructuring and official sector financing, which should both contribute to mitigating liquidity constraints facing developing countries. However, a number of problems remain in the existing Global Financial Safety Net.

First, the urgency of crisis management, especially when the shock is systemic and large, could blur the distinction between solvency and liquidity issues. The design of the DSSI, with the explicit principle of Net Present Value neutrality, focuses on liquidity concerns without fully barring solvency issues. However, the pandemic has made the demarcation between liquidity and solvency problems even finer. Any proposal to tackle the huge and growing debt problems in developing countries cannot treat them as liquidity-originated and, thus, temporary. A quick flash-back to the very slow and painful recovery of Latin America from its debt crisis in the 1980s can give us a sense of how costly it may be to delay the consideration of sovereign debt restructuring as soon as solvency issues are identified.

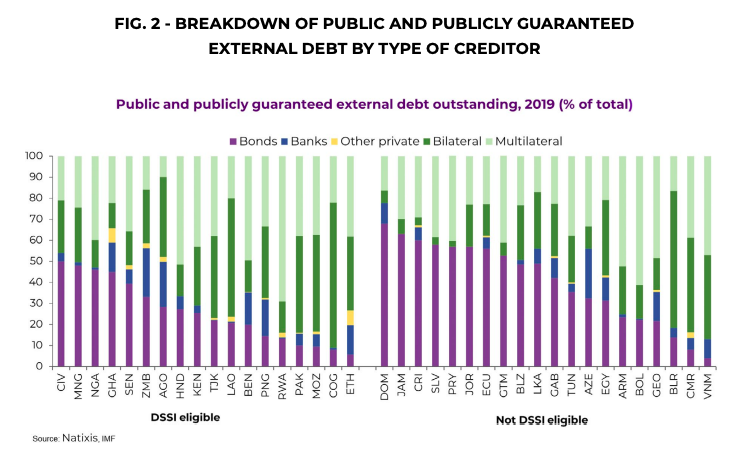

Second, coordination among creditors has become increasingly challenging, given the increasingly diverse nature of creditor groups. Figure 2 shows who holds the sovereign debt of a selection of developing countries. We observe that some developing countries rely heavily on market financing, and thus shy away from potential debt solutions for fear of a potential downgrade of their credit rating as a result. In addition to diverse and scattered private creditors, the world of bilateral official creditors has been evolving as well. China is now a very important official lender, and has contributed more to the implementation of the DSSI than the entire Paris Club.2 In this context, coordination between traditional lenders (such as the Paris Club) and emerging new creditors is key. On the one hand, the magnitude of new financing and, in some cases, debt restructuring provided by China has not been fully incorporated into the policy discussion, partly due to lack of accurate and comprehensive data. The DSSI provided the first formal opportunity for the Paris Club creditors and other major sovereign creditors, including China, to collaborate for a debt payment standstill, despite the relatively small total amount of debt services suspended (US$5 billion by the end of 2020). On the other hand, official sector lenders have primarily relied on the voluntary participation of private creditors or the leverage of the Comparability of Treatment of the Paris Club. However, the Comparability of Treatment only acts upon debtor countries that request debt restructuring with the Paris Club and does not have legal enforcement over private creditors (“sticks”). In other words, the current system does not provide sufficient incentives to attract private creditors either (“carrots”). The failure to unlock the private sector’s contributions to the DSSI epitomises this challenge.

A third issue is the lack of formal mechanisms to facilitate interlinkage between sovereign debt restructuring and financing, for instance through a central broker. The IMF has assumed this broker’s role de facto. In the IMF financial programming, fiscal adjustment and IMF financing are used to close the financing gap of a country facing liquidity challenges. If a country’s debt is deemed unsustainable in the IMF debt sustainability analysis, debt restructuring will need to be included in the IMF financial programming. At the same time, the IMF has long been criticised for having its own skin in the game. In other words, the IMF has the ability to protect its financial resources since it plays a key role in deciding on the size of the financing gap and, thus, the financing needs. Overall, a solution to tackle the mounting and urgent debt problems of such a large number of developing economies needs a clear analytical framework to link new financing to debt sustainability. In addition, it also needs to clarify the role of the IMF as a lender, but also as a broker of other lenders.

Finally, on the financing side, we should also be aware of the limitation on the overall size of resources available for official sector financing and the allocation to individual debtor countries. Resources for crisis management in the Global Financial Safety Net often have pre-set limits. For instance, IMF financing is gauged against member states’ quotas. Access to IMF resources beyond this limit requires special approval by the IMF Executive Board, in line with its Exceptional Access Framework. Other regional mechanisms, with the exception of the European Stability Mechanism, also have pre-set access limits for borrowing. The pre-set limits have their merit in terms of mitigating moral hazard. However, for a systemic external shock like a pandemic, the real hazard of not providing sufficient funding for recovery is probably more harmful than moral hazard. In other words, liquidity provision during a pandemic may need to go beyond standard pre-set limits, such as the IMF quotas.

Proposal

A WORLD RECOVERY FUND TO TACKLE DEBT AND LIQUIDITY PROBLEMS IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD

Given the challenges highlighted above, we aim to add value to the current policy discussion on the debt problems of the developing world. Our proposal, namely creating a World Recovery Fund, aims to linking sovereign financing (new debt) to the treatment of legacy debt. It goes without saying that the WRF is not a silver bullet to solve all debt-related problems in the developing world, but we believe it can help.

To gauge how our proposal might improve the existing situation, we try to link our proposal to the four deficiencies in the current Global Financial Safety Net, and in particular the DSSI, as identified in the previous section. In a nutshell, setting up a WRF should enable emerging countries to swap existing debt for new debt and/or to issue new debt under improved market conditions, with an underlying project as collateral. We detail the key features of this WRF below.

AIMS OF THE FUND AND ACCESSIBILITY

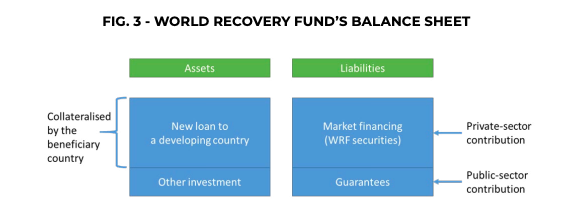

The WRF is a debt redemption fund in nature, designed to help debtor countries exchange highly costly and/or short-term debt for less costly and longer-term debt. It can buy back sovereign debt securities of a given country and swap them with a WRF loan financed by the WRF’s own securities issued in international financial markets. With its financial structure based on guarantees from highly rated countries and/or large official creditors to developing countries (as will be explained in further detail later), the WRF is expected to have a better credit rating than the beneficiary developing countries, thus allowing a swap of higher-risk and costly sovereign debt securities issued by a developing country with a less costly supranational loan provided by the WRF. Figure 3 illustrates the basic structure of the WRF. For readers who are familiar with the set-up of euro area crisis resolution mechanisms, the WRF is inspired by the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF),3 created in 2010 to provide exactly the same type of debt transformation for the euro area countries facing sovereign debt crisis.

A very important issue in the design of the WRF is accessibility criteria. If the accessibility bar is set too high or the process is too complex, many developing countries could be discouraged from taking advantage of this facility, in exactly the same way as a number of countries eligible for the DSSI decided not to request it.4 If the bar is too low, it may risk the sustainability of the WRF. The question, thus, is how to set the bar for access to WRF resources and how to operationalise such a decision. Our proposal is to combine a top-down and bottom-up approach to designing accessibility. The top-down assessment could be based on the longterm debt sustainability of the country soliciting the WRF debt treatment, taking into account the maturity transformation that the WRF could offer, as we will detail below. The most natural broker would be the IMF, as it has been performing this role to assess whether a country can have access to IMF funding.

This top-down approach, however, has proven to be difficult, given the considerable pandemic-related uncertainty surrounding key variables determining debt sustainability, and thus needs to be supplemented. This is why we propose to include a bottom-up approach based on the nature of the project a country wants to finance with the assistance of the WRF and/or the collateral that the country can provide to the WRF for the debt swap. This bottom-up approach could be effectively developed on the basis of the existing project financing models that multilateral banks are using. As for the collateral, it could take various forms, from the most liquid financial assets (e.g. assets in convertible currencies) to the least liquid tangible assets or projects, such as infrastructure developments.

As we will detail below, using tangible assets or projects as collateral brings two advantages. Collateral provides additional financial safety for creditors. More importantly, the WRF aims to channel the new financing – coupled with the conclusion of a debt swap on existing debt – towards investment with high socio-economic returns. The more such projects have positive global externalities (such as in green projects, biodiversity, development of social safety nets, and/or pandemic prevention), the easier it should be for the WRF to engage with the creditors providing guarantees to the fund and market participants from which the WRF gets funded.

BASIC MECHANISM FOR THE WORLD RECOVERY FUND TO HELP A DEVELOPING COUNTRY

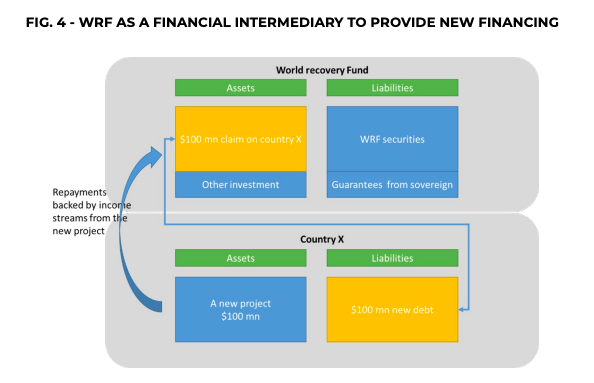

In our framework, there are two ways for the WRF to assist a developing country: new debt issuance and treatment of old debt. In the first and most straightforward scenario, a country X could use the WRF to issue new debt.

Given the high creditworthiness of the WRF (as discussed below), using the WRF as a financial intermediary could be cheaper for country X than issuing debt directly on its own in international financial markets. As Figure 4 shows, the WRF will raise funds from markets and provide a loan to country X. Country X can use this loan to finance a defined project and use the future income streams from the project as collateral to ensure the repayment of the WRF in the future.

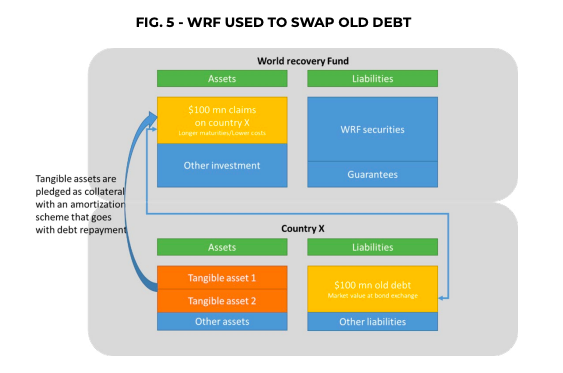

In a second scenario, countries can use the WRF to deal with legacy debt issues, as Figure 5 shows. When facing debt problems, whether liquidity- or solvency-related, the country in question could redeem part of its existing debt stock, say US$100 million to the WRF, which will finance this debt buy-back using the funds raised in international financial markets via its own securities. A natural question that stems from this design is which legacy debt is eligible for buy-back by the WRF, i.e. bilateral official debt or private debt. Theoretically speaking, all old debt could be eligible, but we propose to proceed stepwise. At the inception stage, only bilateral official debt will be eligible, so as to avoid the criticism that public money (in this case financing from the WRF) is used to redeem debt owed to private investors (whether bonds or loans from commercial banks). In addition, sovereign creditors are invited to serve as the WRF’s guarantors, as we will explain in the next sub-section. Should this first step be successful, we could extend the WRF to allow buy-back of private debt from institutional investors. Compared with the first scenario, the second mechanism described above will lower the beneficiary country’s gross financing needs only. Given that country X remains responsible for the principal payment, the WRF could require some forms of collateral to support this debt swap transaction. Country X’s old creditors should also have incentives to resell their holding of country’s X debt (of US$100 million in the example), as their credit risks are lowered.

CONTRIBUTIONS FROM PRIVATE AND OFFICIAL CREDITORS

In the current design, private and official creditors contribute in different ways to the new financing of developing or emerging economies, as well as the swapping of existing debt. Private-sector creditors contribute indirectly, as they would invest in the securities issued by the WRF in international financial markets. For the WRF to be able to raise funds cheaply, it needs to have a minimum solid capital structure, based on guarantees (like the EFSF) or paid-in and callable capital (like the European Stability Mechanism, ESM, or other MDBs). And this is where direct contributions from official creditors come in, under our proposal, as they will need to provide financial resources to fund the WRF. As regards the choice between guarantees and a capital structure with callable and paid-capital, official-sector creditors need to strike a balance between the impact on their own public finances, on the one hand, and the target rating and the resulting borrowing capacity that the WRF could achieve, on the other. The different ratings that the EFSF (based on guarantees) and the ESM (based on capital) enjoy show that paid-in/callable capital provides stronger support for an institution to gain the highest ratings. In addition, the accounting implications for creditors are different. Guarantees are contingent liabilities of guarantee providers and paid-in capital is one-off payment and is moved from the creditors’ balance sheets to the institution’s balance sheet. Cheng and Lennkh (2020) also argue that when the ratings of official creditor countries are not strong, using over-collateralisation (e.g. guarantees provided by official creditors to exceed the institution’s total borrowing from the markets) or increasing the share of paid-in capital could significantly strengthen the creditworthiness of the institution.

For now, we propose that a set of creditor countries provide only guarantees to set up this WRF, according to a pre-set contribution scheme. The contribution scheme could, above all, reflect the current landscapes of the exposure of different creditors to developing countries.

Namely, countries having lent more to developing countries could contribute a larger share of guarantees to the WRF. However, such pre-set contributions alone cannot guarantee a good credit rating for the WRF, as a very large creditor nowadays is China and a few other emerging market economies. A good credit rating is essential to ensure low financing costs for WRF. This means that highly rated creditor countries (e.g. countries with a sovereign rating above AA+) need to be brought in. Therefore, over-collateralisation should be considered, so as to raise the overall ratings of the WRF, following the example.

The remaining question is how to engage different sovereign investors in the WRF. There are a few ways, depending on the circumstances of the creditor. As regards existing creditor countries of developing/emerging economies, pooling together guarantees within the WRF for it to serve as a financial intermediary could lower the financial burden of each single guarantor, given that a group of creditors act in a coordinated manner to provide new financing or to treat legacy debt issues. Beyond the benefits of pooling resources, heavily exposed countries, such as China, can also benefit from the multilateral set-up of the WRF. In fact, a multilateral framework provides stronger legitimacy than bilateral official lending to less developed countries, thus subject to less strong criticism from public opinion. All in all, this framework could also enhance creditor coordination to minimise the consequences of a single creditor restructuring on other creditors (including potential free-riding or first-mover advantage). As regards potential WRF members that are not yet exposed to a specific credit name, but hold a good credit rating, a number of incentives can be set up to attract them. The first is to enhance transparency on lending practices and on the stock of debt of the developing world. Setting data pre-requites for countries accessing WRF financing on their debt structure could entice high-rating countries to participate. In the same vein, earmarking the WRF’s new funding to projects with a high socio-economic return should also help. In other words, funding projects with positive global externalities, i.e. global public goods, should attract general interest and, in particular, encourage highly rated countries to take part in the WRF’s capital by offering guarantees, beyond their relative exposure as creditors to the developing world. In other words, global responsibility for a well-functioning international financial architecture could make the WRF possible beyond a creditor-to-debtor rationale.

INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK AND OTHER OPERATIONAL ISSUES

A new proposal that involves creating a new institution needs to gather enough consensus to go forward. To do so, the most effective way would probably be to use a G20 working group, for instance the International Financial Architecture Working Group, to steer the discussion among G20 members on the design features of the WRF. The most important issue concerns the size of the WRF, which largely depends on the interest of creditor countries and other potential contributors and whether a good credit rating can be achieved, so as to ensure low funding costs. Secondly and relatedly, eligibility criteria need to be properly developed so that the WRF can meet the growing needs for sovereign debt treatment in the future in a viable and sustainable way. Finally, the institutional and governance design of the WRF will be a delicate issue for discussion. For us, the WRF could rely on some existing institutional arrangements within the G20 framework, paired with the IMF as technical adviser and broker, or it could encourage the development of a separate new institution (e.g. an ESM extended to the global level) if there is appetite among G20 members.

In any event, to operationalise our proposal, we still face a number of technical challenges.

First, depending on the size of the World Recovery fund, a balance needs to be struck between the WRF and the development of a primary market for sovereign financing at the national level. Over-reliance on the WRF could potentially distort sovereign debt markets, especially in countries where a large proportion of sovereign debt is in private hands. This could also hamper the country’s capacity to conduct debt management independently. Consideration needs to be given to the question of whether there is an optimal level of sovereign debt that should be issued via the fund to avoid crowding out domestic sovereign markets. For the WRF to play the role of a catalyst, instead of depriving debt issuance from national debt management offices, we can further explore the burden sharing and/or the possibility for a country to use the WRF to fund only at specific debt maturities.

Secondly, there might be national legal constraints on our proposal. For instance, there might be legal impediments to pledge infrastructure or other national tangible assets for new financing. Some existing arrangements, such as sukuks5 and private debt-equity swaps, may provide useful templates

Finally, the current design of the WRF detailed above is based on the guarantees provided by official lenders. In a second stage, we can also consider the possibility of extending the group of guarantors to private investors. This could further strengthen the cooperation and coordination of different groups of creditors for debt treatment but we find it advisable to wait to a second stage to include private creditors, as bail-out and moral hazard risks merit thorough consideration.

NOTES

1 https://www.g20.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Communique-Second-G20-FinanceMinisters-and-Central-Bank-Governors-Meeting-7-April-2021.pdf

2 Bon and Cheng (2021) shows that the share of debt owed to China dwarfed that owed to the Paris Club prior to the recent debt restructurings in Republic of Congo (2017), Zambia (2017) and China (2017).

3 See https://www.esm.europa.eu/efsf-overview

4 In fact, DSSI-eligible countries had to make a request to all their official bilateral creditors, apply for IMF funding and agree to caps on new non-concessional debt, a provision that was later relaxed subject to general guidelines on debt sustainability (Bery et al. 2021).

5 https://gifr.net/gifr2010/contents/ch_09.pdf

REFERENCES

Bery S., A. García-Herrero, and P Weil, “How is the G20 tackling debt problems of the poorest countries?”, Bruegel blog, February 2021

Bolton P., L. Buchheit, P.-O. Gourinchas, M. Gulati, C.-T. Hsieh, U. Panizza, and B. Weder di Mauro, “Sovereign debt standstills: An update”, VOX EU, May 2020

Bolton P., L. Buchheit, P.-O. Gourinchas, M. Gulati, C.-T. Hsieh, U. Panizza, and B. Weder di Mauro, Born out of necessity: A debt standstill for Covid-19, CEPR Policy Insight no. 103, 2020

Bon G. and G. Cheng, “Understanding China’s role in recent debt relief operations: A case study analysis”, International Economics, vol. 166, 2021, pp. 23-41

Cheng G. and A. Lennkh, RFAs’ financial structures and lending capacities: a statutory, accounting and credit rating perspective, ESM Working Papers 44, 2020

García-Herrero A. and E. Ribakova, “COVID-19’s reality shock for emerging economies: Solutions to deal with dependence on external funding”, VOX EU, May 2020