The fragmentation of international investment agreements (IIAs) is an urgent issue for reform because fragmentation results in divergent levels of protection and inconsistencies in applying and interpreting treaty provisions.

This brief suggests that reducing fragmentation and enacting a multilateral or plurilateral investment agreement covering jurisdiction, substantive protection, and procedure, would increase investment and empower small and medium size enterprises (SMEs) to invest. Reforms must go beyond mere investment/investor protection to a more comprehensive set of objectives including sustainable development, dispute prevention, environmental protection, and protecting SME investments.

A second recommendation relates to a new “institutionalization” by proposing that any new institution is headquartered in an emerging market outside traditional Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) centers.

Challenge

The legitimacy of the existing system of international investment law has been debated in recent years because it relies on Investor-State Dispute Settlements (ISDS), a system based on international commercial arbitration. Several international stakeholders propose significant reforms either within the existing system (e.g., the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes [ICSID]), or potentially more substantial and radical reforms (e.g., within the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law [UNCITRAL]), which could lead to the abolition of the current arbitration regime and its replacement with a Multilateral Investment Court.

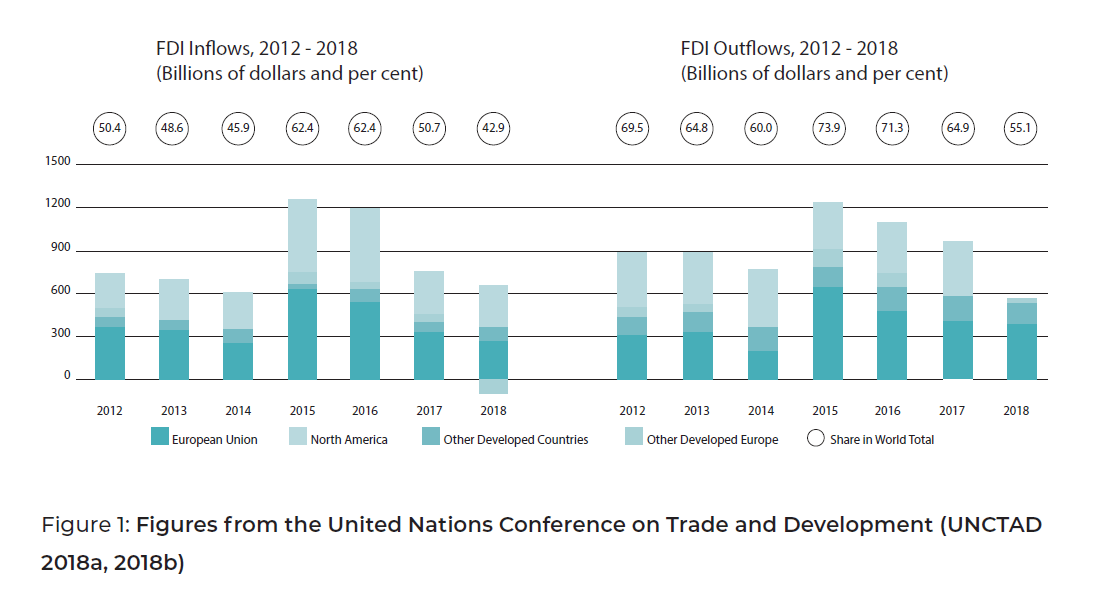

The main advantage of the current regime is its neutrality and non-political character. However, some current reform discussions exhibit a return to nationalist populism and politicization, as new disputes often become domestic political controversies. A new system might safeguard neutrality and support depoliticization, but could also affect investor perceptions and foreign direct investment (FDI) flows[1]. In that case, reverting to national courts may be a tempting solution, but risks further fragmentation of the system, which would lead to gross inconsistencies. It is essential to have international investment agreements (IIAs) interpreted and applied by internationally minded adjudicators who respect the origin and application of IIA norms, emancipated from domestic notions and prejudices.

It is pertinent to explore all possible solutions involving both procedural and substantive law to ensure multilateralism and upholding of the rule of law, as well as enhance investment protection and promotion. Investment flows and sustainable FDI are key objectives of all countries, both developed and developing. While it is inevitable that investment flows are unevenly distributed in the global economy, with some countries being net FDI importers and others being net FDI exporters (UNCTAD n.d.), facilitation of investment flows is beneficial for both. FDI exporters are also major FDI importers, and FDI flows contribute to global financial growth.

The fragmentation of IIAs is an urgent issue for reform because fragmentation results in divergent levels of protection and inconsistencies in applying and interpreting treaty provisions.

This brief suggests that reducing fragmentation and enacting a multilateral or plurilateral investment agreement covering jurisdiction, substantive protection, and procedure would increase investment and empower small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to invest. Reforms must go beyond mere investment/investor protection to a more comprehensive set of objectives including sustainable development, dispute prevention, environmental protection, and protecting SME investments.

A second recommendation relates to a new “institutionalization” by proposing that any new institution is headquartered in an emerging market outside traditional ISDS centers.

Challenges to be addressed include:

- Tackling global trade imbalances and protectionism,

- Attracting sustainable FDI,

- Fostering a supportive, open, and inclusive trade and investment system,(d) Enhancing trade policies and agreements, and (e) Confronting challenges for SMEs.

The objective is to include recommendations that form policy guidelines in order to enact a multilateral or plurilateral investment agreement (MIA or PIA) covering both substantive law and procedural law matters, and addressing jurisdictional concerns. Such comprehensive reform would ensure both a new global covenant for international investment and that foreign investment is effectively promoted and protected.

It is also critical to have recommendations for dispute avoidance and dispute prevention, as dispute settlement mechanisms ought to be a last resort. It is critical to involve both developed and developing countries in working conferences; countries with diverse socio-economic backgrounds and cultures; as well as various stakeholders, including legal representatives.

The current system is highly fragmented, with more than 3,000 IIAs (bilateral investment treaties [BITs]), several free trade agreements (FTAs), and a series of regional or sectoral multilateral investment agreements. There are various ways of addressing fragmentation, but a compelling option would be enactment of an MIA or a PIA, which would not only address inconsistencies and fragmentation, but would also create a level playing field. Such an agreement would eliminate the need to resort to mechanisms such as most-favored-nation clauses. The drafting of a new MIA or a PIA aligned with the current objectives of sustainable development would provide a better framework for investment facilitation, regulation, promotion, and protection. This would enable developing countries to better formulate their objectives, not only as FDI recipients, but also as potential FDI exporters, while balancing their own needs with the objectives of developed economies. An MIA or a PIA would build upon the G20 Guiding Principles for Global Investment Policymaking developed in 2016. A new MIA or a PIA must be supported by a new institution that should be located in a G20 country that is an emerging market, and not a traditional ISDS center. Placing the new institution outside a traditional ISDS center would stimulate regional interest and foster FDI growth while building capacity.

This policy brief aligns with the G20 “Empowering People” agenda and the objectives of Task Force 1, as it deals with financial nationalism: attracting sustainable FDI; fostering a supportive, open, and inclusive trade and investment system; enhancing trade policies and agreements; and supporting SMEs. The G20 provides a unique forum for idea exchange and policy promotion. The aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic will also impact FDI flows, claims contemplated by investors, and the prospect of such claims when states impose restrictions as they reopen.

Proposal

1. Introduction

This policy brief identifies the persistent fragmentation of IIAs as an urgent issue for reform. This is true in both the BIT and FTA forms, resulting in divergent levels of protection and inconsistencies in the application and interpretation of the provisions of these treaties, mainly by arbitral tribunals[2].

This brief suggests that reducing fragmentation or even abolishing the current investment regime and replacing it with an MIA or a PIA covering jurisdiction, substantive protection, and procedure, will have a positive impact on investment facilitation and, with adequate protections, would empower SMEs to invest.

During the reform process, it is essential to expand the system’s objectives from mere protection of investments and investors to more comprehensive objectives that include sustainable development; investment facilitation and promotion; dispute avoidance and prevention; protecting corporate social responsibility, investor responsibility, and the environment; and facilitating access of SMEs to investment protection.

An additional suggestion proposes a new “institutionalization,” while ensuring that any new institution has its headquarters in an emerging market and outside the traditional ISDS centers.

2. Historical Approach

2.1. ISDS and Investment Protection

International investment law developed as a system of legal protections for investors from developed states that invested in less developed states. Proponents of the system maintained that it encouraged the flow of capital, technology, and management expertise to states where they were most needed. From this origin, the system has diversified to protect investments originating from and destined for both developed and developing states.

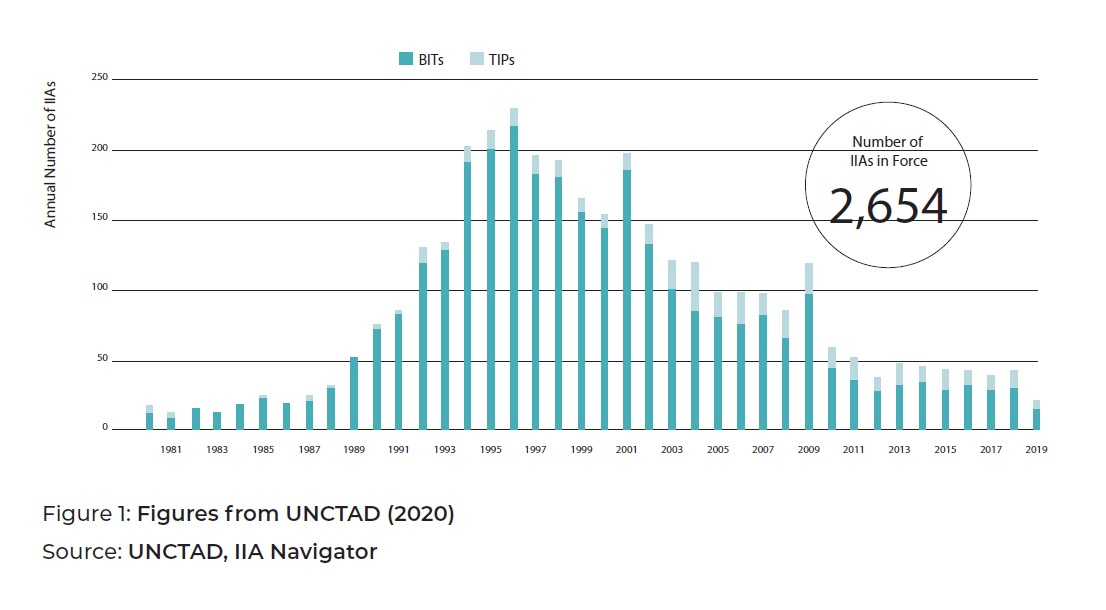

Legal protections for investments were first introduced into state contracts (Quak 2018, 2–3) in the late 19th century, and later into bilateral and multilateral treaties with investment protections. The current regime took shape during the early 1960s[3]. A common feature of current investment treaties is that they place obligations on states but not on investors. Attempts to conclude a multilateral instrument with substantive protections that would attract broad membership, as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade has achieved for trade, have proven unsuccessful (with some notable exceptions, like the CP-TPP) (2018). There are now more than 3,280 treaties (with 34 treaty terminations and 22 new treaties in 2019) and no fewer than 2,654 IIAs in force that specify investment protections. Developed, developing, and transitional economies have all been active in concluding IIAs. The obligations in those instruments tend to be similar in substance but are expressed in broad and sometimes ambiguous terms.

Individuals and businesses mistreated by their host states abroad have historically relied on their home states to pursue remedies through international diplomacy, which effectively shifts the control over the outcomes of investors’ activities to states. In contrast, investment instruments have established the right of investors to bring international arbitration claims directly against the states hosting their investments. Typical disputes would arise out of direct or indirect expropriation without compensation, treatment which falls short of the practices specified by the fair and equitable treatment standard, and discriminatory conduct by states, notably in the form of taxation, refusal of certain benefits, or prevention of market access by refusal to issue licenses. The arbitrators in these proceedings are chosen by the parties, and at times, with assistance from institutions. The awards from proceedings are typically published, and tend not to be subject to appeal on grounds of mistakes of law or misinterpretation of facts by tribunals.

The increase in foreign investment beginning after World War II, combined with the growth in the number of investment treaties in the early 1990s, resulted in a rapid increase in investor-state arbitrations that began in the late 1990s[4]. It is estimated that there have been at least 1,000 investor-state arbitrations since then (IIA 2019,1). The growth in the number of arbitrations and the imprecise expressions of state commitments in treaties have resulted in a shift of responsibility for interpreting state commitments in treaties from the state treaty parties to arbitrators. Meanwhile, the lack of a formal system of precedent and the substantial fragmentation of international treaties means that arbitrators have sometimes interpreted identical or similar provisions differently.

The ICSID was established in 1966 to facilitate international investment dispute settlement. The ICSID provides procedural rules and administrative services for this purpose and has overseen about 70% of investor-state arbitrations[5]. Among other dispute-resolution processes, the ICSID administers self-contained arbitration proceedings, independent of any place of arbitration, to disputants that qualify under the ICSID Convention. This process has treaty-based procedures for challenging arbitrators and arbitral awards, and enforcing arbitral awards.

Investor-state arbitrations have also been administered by other institutions, including the Permanent Court of Arbitration[6], and heard in ad hoc proceedings without institutional support. Non-ICSID arbitrations commonly proceed under the arbitration rules of the UNCITRAL[7]. Like commercial arbitrations, proceedings outside of the ICSID Convention have a designated place of arbitration whose courts may be called on to support the proceedings. Awards issued from these arbitrations are enforced under the New York Convention, concluded in 1958 (United Nations 1958), primarily for the benefit of commercial awards. The New York Convention served as a model for a similar enforcement treaty that governs mediation. In September 2020, the United Nations Convention on International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation will come into force with the purpose of facilitating the enforcement of settlement agreements that result from mediation (2020).

There are two specific concerns about the current fragmented systems.

- Absolute Treatment Standards. State commitments that are not contingent on outside events or state treatment of other investors. These commitments are grouped under two standards:

- The “full protection and security” standard[8]

- The “fair and equitable treatment” (FET) standard[9]. A recurring and divisive issue in arbitral decisions is whether the FET provision demands a higher standard of treatment than the minimum standard owed to foreigners by states under customary international law10, with the new generation of IIAs delimiting definitions of the FET11.

- Relative Treatment Standards which seek to prevent discrimination among investors. Compared to absolute standards, they require a comparison of treatment given to claimant investors and other investors. Such treatment is of two broad types:

- “national treatment” (NT)12

- “most-favored-nation (MFN) treatment.13” A contentious issue for the past two decades has been whether MFN treatment can be used by investors to improve access to arbitration14. One reason for the controversy, according to many commentators, is that this application of the standard interferes with both party consent and the jurisdiction of arbitral tribunals.

2.2. IIAs—BITs and FTAs

IIAs have become the basis of significant jurisprudence, with more than 1,000 known cases (2020b), and the subject of much scholarly writing. We present some of the key issues in outline form:

a. Jurisdictional issues include:

- The notion of “foreign” investment and issues associated with investment structuring and restructuring. Under ISDS jurisprudence, investors can structure their investments by establishing companies in countries with favorable investment protection regimes with the host state (Dolzer and Schreuer 2012, 5215). This is because most treaties only require “incorporation” as a criterion to establish a tribunal’s jurisdiction, and as long as a company is validly incorporated, treaty requirements are met. Such “nationality planning” or “treaty shopping” is not considered illegal. Nevertheless, it would likely be undesirable from a host state’s perspective, and many tribunals have upheld corporate nationality thus obtained16. The situation is different if an investor attempts to restructure their investment in order to obtain the benefit of an IIA17. To curtail treaty shopping, however, states have begun incorporating denial of benefits’ clauses into treaties18, and have considered restricting definitions of “investors” and “investments” (Chaisse 2015, 289). This is happening in many modern IIAs. For example, some states now require “substantial business activities” in addition to incorporation to determine corporate nationality.

- Shareholders’ claims and reflective loss. One issue is whether shareholders should be able to bring claims independent from those by the company in which they have invested. Another is whether the right to make claims should be limited to majority shareholders or also include minority shareholders (Arato et al. 2019, 12).

b. Substantive standards issues include:

- Expropriation. States have the right to lawfully expropriate property under customary international law (Dolzer and Schreuer 2012, 98; Cox 2019, 11). Treaty law confirms this right and specifies conditions for lawful expropriations (Dolzer and Schreuer 2012, 100). The appropriate standard for establishing expropriation is substantial deprivation of “the economic use and enjoyment”19 of the investment that “must be permanent and irreversible.20”

- Umbrella clauses and contract claims. Umbrella clauses are designed to bring commitments made by host states to foreign investors, usually in contractual agreements, under the protective umbrella of the investment treaty (Schreuer 2004). Questions have been raised on whether the effect of the clause is to elevate a contractual breach to a breach of the BIT under international law. In practice, in SGS. Pakistan, the first case to interpret an umbrella clause, the tribunal concluded that contractual breaches could not per se amount to a breach of the BIT21. In SGS. Philippines, the tribunal concluded that the effect of the umbrella clause was to make a contractual breach a breach of the BIT “[without converting it] into an issue of international law22.”

- State defenses and counterclaims. The primary concern is that traditional IIAs have been designed to provide investor remedies without balancing the obligations on states with clearly developed state defenses and capacity for counterclaims. This is being gradually addressed in contemporary IIAs.

2.3. ISDS procedural reforms

In the last few years, a number of reform projects have focused on procedure. The ICSID has started modernizing various sets of procedural rules, and for the first time has promulgated mediation rules23. In 2018, UNCITRAL embarked on a large-scale project of addressing legitimacy concerns24. A paper by the Center for International Dispute Settlement (Kaufmann and Potestà 2016) has been the springboard for the UNCITRAL agenda, and this process has been enhanced by papers produced, inter alia, by governments25, the ISDS Academic Forum, and the Corporate Counsel International Arbitration Group (CCIAG) (2019). Queen Mary University of London and the CCIAG also conducted the first-ever empirical survey canvassing the views of investors on the UNCITRAL reform agenda26. Key issues addressed by the current reform agenda include:

a. Efficiency (Mistelis 2020).

b. Transparency. The ISDS is facing an increased demand for transparency “to enhance [its] effectiveness and continued [public] acceptance,” (OECD 2005, 11) given the public interest. In 2013, UNCITRAL adopted the Rules on Transparency in Treaty-Based Investor-State Arbitration which applies to all treaties concluded on or after April 1, 2014 that specify UNCITRAL arbitration. This was followed by the UN Convention on Transparency in Treaty-based Investor-State Arbitration (Mauritius Convention) (2015a).

c. Third party participation. One concern relating to transparency is the participation of third parties in ISDS, either as amici or as non-disputing parties (NDP) in the case of states (Mistelis 2005, 169-199). The ICSID Arbitration Rule 37(2) permits tribunals to accept submissions by non-disputing parties after consulting with both parties[27].

Rule 32(2) of the ICSID allows the tribunal to let third parties observe all or part of any hearings, subject to logistical arrangements. A survey of the ICSID cases has revealed that amici and NDP submissions are not used to their full potential by tribunals (Butler 2019). The Mauritius Convention simply extends the application of the Rules on Transparency to all investor-state disputes (United Nations 2015a). The Rules on Transparency deal with NDP participation, and do not differ significantly from the regime under the ICSID Arbitration Rules.

d. Pre-conditions/alternatives to arbitration. States have increasingly considered preconditions to ISDS, such as exhaustion of local remedies[28], or pursued alternatives to ISDS, such as an Investment Court System (ICS)[29]. An increased reliance on domestic courts through exhaustion of local remedies, along with support for states with less developed legal systems, can strengthen rule of law and consistency of domestic jurisprudence while also reducing the cost of dispute resolution (UNCTAD 2015, 149). Rule of law concerns respect for fundamental rights, formal legality (Schultz and Dupont 2014, 1163), and substantive justice[30]. In the context of investment law and ISDS, the application of the law by arbitral tribunals in a competent and impartial manner (Schultz and Dupont[31] 2014, 1163), as well as the predictability and transparency of the rules and of the adjudication system, are of high relevance. Meanwhile, the challenge in substituting ISDS with an ICS is to overcome its shortcomings while building on its strengths, such as neutrality, enforceability, and manageability (Kingdom of Bahrain 2019, 1). However, criticisms leveled against the European ICS provisions suggest that they fall short on the counts of finality, efficiency, and enforceability. At the same time, there is a significant drive to promote investor-state mediation, mediation in general, and dispute prevention mechanisms. Legal scholars have written recently, “All institutional processes are imperfect, and all of them are imperfect in different ways given the dynamics of participation within them” (Puig and Shaffer 2018).

e. Introduction of an appellate mechanism. One of the most important proposals to reduce inconsistency in ISDS is to introduce an appellate mechanism. China, the EU, USA and other countries have expressed support for this mechanism. The nature and scope of such an appellate mechanism, however, are being debated.

3. Fostering and Enhancing Investment Protections

3.1. Methods

There are many different approaches to fostering investment facilitation and enhancing investment protection, through investment regulation at the domestic or global level. Possible methods include:

(a) Drafting a new MIA or PIA covering procedure, issues of jurisdiction, and substantive protection.

(b) Investment guidelines or another soft instrument, possibly a model law regulating investment promotion, regulation, and protection.

(c) Institution and capacity building by encouraging the creation of a new center in an emerging economy, ideally within a G20 country, but outside the traditional ISDS centers.

For all options, there is the question of which international organization should take the lead to effect developments. There are arguments both for and against existing intergovernmental agencies (e.g, UNCITRAL, UNCTAD or ICSID) playing this role. Another option is a political initiative by the G20 to build adequate consensus; then the project can be transferred either to an existing intergovernmental agency, or a new agency can be created (Shan 2018).

3.2. Scope (substance, procedure, jurisdiction or combinations)

Defining the scope of reform is essential for the success of any reform project, and any discussion in this policy brief is without prejudice to any work currently undertaken by organizations such as ICSID and UNCITRAL. Further, the scope must be tailored to work hand-in-hand with other methods and objectives.

An MIA or aPIA, or any guidelines or model law, could cover:

(a) Substantive protection and investment promotion and regulation only;

(b) Substantive protection, and investment promotion and regulation, together with ISDS procedures and dispute avoidance and prevention mechanisms (but without covering issues of jurisdiction);

(c) Substantive protection and investment promotion and regulation, together with ISDS procedures; dispute avoidance and prevention mechanisms; and issues of jurisdiction.

The broader the scope of the reform, the greater the uniformity and elimination of fragmentation, but the longer the process to achieve consensus and the higher the level of compromise in order to reach consensus. The narrower the scope of the reform, the lower the uniformity and elimination of fragmentation, but the quicker the process of consensus.

There is also the option of other types of reform, either de novo reform (a blank canvas approach) or reform based on existing documents, treaties, and international customary law.

3.3. Objectives (sustainability, protecting social responsibility and environment)

The international legal regime concerning FDI should play a significant role in fostering a healthy regulatory climate for investment. Investment is a primary driver of the UN 2030 Agenda on Sustainable Development (2015b), which requires robust flows of capital, technology, and skills across borders. In the wake of pressing global economic, environmental, and social challenges, policymakers are increasingly expected to focus on the qualitative dimension of FDI.

The need for improved coherence in international investment policymaking is emerging from various quarters. It is possible to reconcile the private interests protected by international investment law with global interests such as human rights, the environment, and the fight against climate change. This can be done through coherent law-making and systemic integration in the process of interpretation and application of IIAs.

In this respect, UNCTAD has formulated a comprehensive set of principles for investment policymaking that provide guidance for investment policies that foster sustainable development (2015a). Similarly, the G20 Guiding Principles for Global Investment Policymaking of 2016 encourage investment policies that are “consistent… with sustainable development and inclusive growth (G20 2016, ¶V)32”, and “promote and facilitate the observance by investors of international best practices (G20 2016, ¶VIII)33.”

Against this backdrop, an increasing number of model investment agreements and actual agreements contain “non-lowering of standards” clauses, provisions preserving states’ regulatory autonomy, and clauses encouraging or requiring investors’ upfront compliance with human rights and environmental standards.

International normative consistency on investors’ obligations could benefit from drawing from the due diligence standards increasingly adopted under domestic legislations.

3.4. Institutions and capacity building

The last of our proposals in this policy brief addresses global capacity building to facilitate investment flows, empower SMEs, and enhance investment promotion, regulation, and protection. The current proposals at UNCITRAL for anadvisory center are yet to be developed fully. The investor survey by Queen Mary University of London and CCIAG suggests that creation of such a center would be a positive step[27]. However, the question remains whether the current reform work would culminate in such a capacity building center and whether something different may be needed.

If the ISDS, dispute prevention and avoidance, as well as investor-state mediation are involved in current reforms, a new ISDS institution might be needed, perhaps located in a G20 country but outside traditional ISDS centers. Such an institution would have immunity and a headquarters agreement with the country in which it is situated. It could alleviate the need for a BRICS center, which has been discussed for years.

4. Recommendations

The current COVID-19 pandemic affects every aspect of human behavior and economic activity, and has resulted in an inevitable and unprecedented fall in global trade and investment. Any solution must result from co-operation and ultimately be global, as is the crisis. Hence, the pandemic provides an excellent opportunity to rethink globalization and global solutions. The current fragmentation in investment agreements is no longer tenable. We should strive for a comprehensive multilateral investment agreement covering both substantive law and procedural law matters while addressing jurisdictional concerns. We should also consider the creation of an institution to support such a multilateral agreement. Multilateralism and global cooperation are not just objectives: they are an urgent necessity.

Arguably, the most important lesson from the pandemic is that global issues require global cooperation and coordination in terms of solutions. For example, even if a vaccine is developed by a team of researchers in China, the UK, the USA or elsewhere, it is important to note that: (a) such teams are international in their composition; (b) tests will have to be carried out in several countries; and (c) ultimately, the commercial development and distribution of a vaccine will require global efforts.

In the same vein, this policy brief proposes that reducing fragmentation and replacing it with a (global) MIA or PIA covering jurisdiction, substantive protections, and procedures would have an undisputedly positive impact on investment facilitation and encourage SMEs to invest.

A global MIA or PIA would require an open dialogue and debate bringing together businesses, states, and academia, while taking into account the needs and peculiarities of developed and developing states. A great deal of background work has already been done. It is essential, however, to recalibrate the focus of attention from mere investment or investor protection to a more comprehensive set of objectives, namely investment regulation, promotion, and protection; sustainable development; investment facilitation and promotion; dispute prevention; promotion of corporate social responsibility and investor responsibility; as well as protecting the environment (climate change objectives) and facilitating access of SMEs to investment protection. The focus should now shift to investment promotion and regulation rather than investor protection, and solutions must provide fair access to investment for SMEs.

A second recommendation relates to new “institutionalization.” A new MIA or PIA should be supported by a new institution to be located in a G20 country that is both an emerging market and not a traditional ISDS center. Such an institution could be either entirely independent or work in conjunction with the ICSID and Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) or the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) Court of International Arbitration. It could equally provide policy advisory work, capacity building and training, and a hearing center where ISDS cases can be heard. It would not compete with other institutions but act in concordance and co-operation. It could even host a multilateral investment court if the current arbitration regime were to be reformed in that way.

In summary, we propose that:

- The G20 issue a call for an MIA or a PIA covering both substantive law and procedural law matters and addressing jurisdictional concerns, together with a work plan for the future.

- The G20 support the creation of a new institution in an emerging economy, ideally within a G20 country, but, outside the traditional ISDS centers.

Disclaimer

This policy brief was developed and written by the authors and has undergone a peer review process. The views and opinions expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the authors’ organizations or the T20 Secretariat.

References

Arato, Julian, Kathleen Claussen, Jaemin Lee, and Giovanni Zarra. 2019. “Reforming Shareholder Claims in ISDS” Academic Forum on ISDS Concept Paper 2019/9, Last updated September 29, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3433465.

Butler, Nicolette. 2019. “Non-Disputing Party Participation in ICSID Disputes: Faux Amici.” Netherlands International Law Review 66, 143–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40802-019-00132-8.

Chaisse, Julien. 2015. “The Treaty Shopping Practice: Corporate Structuring and Restructuring to Gain Access to Investment Treaties and Arbitration.” Hastings Business Law Journal 11, no. 2: 289.

Corporate Counsel International Arbitration Group (CCIAG). 2019. “Investor-State Dispute Settlement (IDIS) Reform.” Submission to UNCITRAL Working Group III. December 18, 2019. https://uncitral.un.org/sites/uncitral.un.org/files/cciag_isds_reform.pdf.

Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership

(CPTPP). 2018. https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/in-force/cptpp/Pages/comprehensive-and-progressive-agreement-for-trans-pacific-partnership.

Cox, Johanne. 2019. Expropriation in Investment Treaty Arbitration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dolzer, Rudolf, and Christoph Schreuer. 2012. Principles of International Investment Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

ICSID. n.d. “Guide to Membership in the ICSID Convention.” World Bank webpage, https://icsid.worldbank.org/about/member-states/guide-to-membership.

ICSID. n.d. “ICSID Convention.” World Bank webpage. https://icsid.worldbank.org/en/Pages/icsiddocs/ICSID-Convention.aspx#:~:text=%E2%80%8BThe%20ICSID%20Convention%20is,by%20the%20first%2020%20States.

International Investment Agreements (IIA). 2019. “Fact Sheet on Investor-State Dispute Settlement Cases in 2018.” IIA Issues Note May 2019, no. 2. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/diaepcbinf2019d4_en.pdf.

International Investment Agreements. 2020a. “The Changing IIA Landscape: New Treaties and Recent Policy Developments.” IIA Issues Note July 2020, no. 1. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/diaepcbinf2020d4.pdf.

International Investment Agreements. 2020b. “Investor-State Dispute Settlement Cases Pass the 1,000 Mark: Cases and Outcomes in 2019.” IIA Issues Note July 2020, no. 2. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/diaepcbinf2020d6.pdf.

Kaufmann-Kohler, Gabrielle, and Michele Potestà. 2016. “Can the Mauritius Convention serve as a model for the reform of investor-State arbitration in connection with the introduction of a permanent investment tribunal or an appeal mechanism?” CIDS website, Research Paper. Last updated June 3, 2016. https://www.uncitral.org/pdf/english/CIDS_Research_Paper_Mauritius.pdf.

Kingdom of Bahrain. 2019. “Possible Reform of Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISID): Comments By the Kingdom of Bahrain.” United Nations Commission on International Trade Law website. https://uncitral.un.org/sites/uncitral.un.org/files/uncitral_wg_iii_bahrain_submission_31_ july_2019.pdf.

Mistelis, Loukas. 2005. “Confidentiality and Third Party Participation UPS v. Canada and Methanex Corporation v. United States.” Arbitration International 21, no. 2: 205–225. https://doi.org/10.1093/arbitration/21.2.211.

Mistelis, Loukas, and Crina Baltag. 2018. “‘Denial of Benefits’ Clause in Investment Treaty Arbitration” (December 13, 2018). Queen Mary School of Law Legal Studies Research Paper No. 293/2018. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3300618.

Mistelis, Loukas. 2020. “Efficiency. What Else? Efficiency as the Emerging Defining Value of International Arbitration: between Systems theories and party autonomy.” In The Oxford Handbook of International Arbitration, edited by Thomas Schultz and Federico Ortino, 349–376. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

OECD. 2005. “Transparency and Third Party Participation in Investor-State Dispute Settlement Procedures.” OECD Working Papers on International Investment, 2005/01. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/investment-policy/WP-2005_1.pdf.

Puig, Sergio, and Gregory Shaffer. 2018. “Imperfect Alternatives: Institutional Choice and the Reform of Investment Law.” American Journal of International Law 112, no 3: 361–409. https://doi.org/10.1017/ajil.2018.70.

Quak, Evert-Jan. 2018. “The Impact of State-Investor Contracts on Development.” Institute of Development Studies website, Helpdesk Report. Last updated August 10, 2018. https://www.ids.ac.uk/download.php?file=wp-content/uploads/2018/12/The-Impact-of-State-Investor-Contracts-on-Development.pdf.

Schreuer, Christoph. 2004. “Travelling the BIT Route: of Waiting Periods, Umbrella clauses and Forks in The Road.” Journal of World Investment & Trade 5 no. 2: 231–256. https://doi.org/10.1163/221190004X00443.

Schultz, Thomas, and Cédric Dupont. 2014. “Investment Arbitration: Promoting the Rule of Law or Over-empowering Investors? A Quantitative Empirical Study.” European Journal of International Law 25, no. 4: 1147–1168. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chu075.

Shan, Wenhua. 2015. “Toward a Multilateral or Plurilateral Framework on Investment.” E15 Task Force on Investment Policy, Think Piece. Last updated November 2015. https://e15initiative.org/publications/toward-a-multilateral-or-plurilateral-frameworkon-investment.

Southern African Development Community. 2012. “SADC Model Bilateral Investment Treaty Template With Community.” Botswana: SADC. https://www.iisd.org/itn/wpcontent/uploads/2012/10/sadc-model-bit-template-final.pdf.

UNCTAD. n.d. “Foreign Direct Investment: Inward and Outward Flows and

Stocks, Annual.” UNCTAD STAT website, table. https://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=96740.

UNCTAD. 2015a. “Investment Policy Framework For Sustainable Development.” UNCTAD website, PDF. Policy framework. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/diaepcb2015d5_en.pdf.

UNCTAD. 2015b. “World Investment Report 2015: Reforming International Investment Governance.” Geneva: UNCTAD. https://unctad.org/en/pages/PublicationWebflyer.aspx?publicationid=1245.

UNCTAD. 2018a. “Developed Economies: FDI Flows, Top 5 Host Economies, 2018.” UNCTAD website, PDF. https://unctad.org/Sections/dite_dir/docs/WIR2019/WIR2019_FDI_Developed_Economies_en.pdf.

UNCTAD. 2018b. “Least Developed Countries: FDI Flows, Top 5 Host Economies, 2018.” UNCTAD website, PDF. https://unctad.org/Sections/dite_dir/docs/WIR2019/WIR2019_FDI_Least_Developed_Countries_en.pdf .

United Nations. 1958. “Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of

Foreign Arbital Awards.” UN Treaties website, PDF. https://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/1959/06/19590607%2009-35%20PM/Ch_XXII_01p.pdf.

United Nations. 2015a. “United Nations Convention on Transparency in Treaty-Based Investor-State Arbitration.” United Nations Commission on International Trade Law website. PDF. https://www.uncitral.org/pdf/english/texts/arbitration/transparencyconvention/Transparency-Convention-e.pdf.

United Nations. 2015b. “Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform. PDF. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf.

United Nations. 2019. “Convention on International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation.” United Nations Treaty Collection website. https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXII-4&chapter=22&clang=_en.

Appendix

[1] . We also want to point out the empirical uncertainty about whether the existing system has resulted in an increase in FDI flows.

[2] . This is part of the larger picture of fragmentation of public international law. See International Law Commission (ILC), Fragmentation of International Law: Difficulties Arising from the Diversification and Expansion of International Law—Report of the Study Group of the International Law Commission UN Doc. A/CN.4/L.682 (Apr. 13, 2006), as corrected UN Doc. A/CN.4/L.682/Corr.1 (Aug. 11, 2006) (finalized by Martti Koskenniemi).

[3] . The BIT between Germany and Pakistan which entered into force in 1961 was the first of the new generation of BITs. Treaty between The Federal Republic of Germany and Pakistan for the Promotion and Protection of Investments, Germ.-Pak., November 25, 1959, UNTS Bd 457 S 23.

[4] . See IIA 2019 (reporting 942 cumulative arbitrations including ICSID and non-ICSID cases through 2018), and the ICSID website (reporting 80 registered cases from January 1, 2019 to April 6, 2020).

[5] . ICSID, Guide to Membership in the ICSID Convention, 1, https://icsid.worldbank.org/en/Documents/about/Guide%20to%20Membership%20in%20the%20ICSID%20Convention%20-%20EN.pdf.

[6] . Founding Conventions of the Permanent Court of Arbitration are: the Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes, July 29, 1989, https://docs.pca-cpa.org/2016/01/1899-Convention-for-the-Pacific-Settlement-of-International-Disputes.pdf; Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes, October 18, 1907, https://docs.pca-cpa.org/2016/01/1907-Convention-for-the-Pacific-Settlement-of-International-Disputes.pdf.

[7] . The United Nations Commission on International Trade Law was established by the UN General Assembly, Resolution 2205(XXI) UNCITRAL, Establishment of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law, December 17, 1966, https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/2205(XXI). See United Nations (1958).

[8] . For example, Article 3(1) of the Germany-Turkey BIT: “[i]nvestments… shall enjoy protection and security in the territory of the other Contracting Party’”; Treaty Between the Federal Republic of Germany and the Republic of Turkey Concerning the Reciprocal Promotion and Reciprocal Protection of Investment, Ger.-Tur., June 20, 1962, https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreement/treaty-files/1438/download. Treaties cited in this paper can be viewed on the Investment Policy Hub of the UNCTAD website, https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org.

[9] . For example, Article VII(1) of the Netherlands-Singapore BIT (1972): “[e]ach Contracting Party shall ensure fair and equitable treatment to the investments of nationals of the other Contracting Party”). Agreement on Economic Cooperation Between the Government of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Government of the Republic of Singapore, Neth.-Sing., May 16, 1972, https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements/treaty-files/2079/download.

[10] . Compare the 2009 award in Cargill v Mexico, ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/05/2, Award, September 18, 2009 para. 284 (interpreting FET to prevent egregious state conduct) https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0133_0.pdf; and the 2010 award in Merrill v Canada, ICSID Case No. UNCT/07/1, Award, March 31, 2010, para 210, (interpreting the FET standard to prevent unreasonable state conduct) https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0504.pdf; awards and decisions referred to in this brief are available at https://www.italaw.com.

[11] . See, for example, the Comprehensive Economic Trade Agreement, EU-Canada, October 30, 2016, 8.10:

2. A Party breaches the obligation of fair and equitable treatment referenced in paragraph 1 if a measure or series of measures constitutes:

(a)denial of justice in criminal, civil or administrative proceedings;

(b)fundamental breach of due process, including a fundamental breach of transparency, in judicial and administrative proceedings;

(c) manifest arbitrariness;

(d) targeted discrimination on manifestly wrongful grounds, such as gender, race or religious belief;

(e) abusive treatment of investors, such as coercion, duress and harassment; or

(f) a breach of any further elements of the fair and equitable treatment obligation adopted by the Parties in accordance with paragraph 3 of this Article.

4. When applying the above fair and equitable treatment obligation, the Tribunal may take into account whether a Party made a specific representation to an investor to induce a covered investment, that created a legitimate expectation, and upon which the investor relied in deciding to make or maintain the covered investment, but that the Party subsequently frustrated.

[12] . For example, Article 3(1) of the Germany-Namibia BIT (1994): “[n]either Contracting Party shall subject investments…to treatment less favourable than it accords to investments of its own nationals or companies.” Treaty between the Federal Republic of Germany and the Republic of Namibia concerning the Encouragement and Reciprocal Protection of Investments, Ger.-Nam., January 21, 1994 https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements/treaty-files/1377/download.

[13] . For example, Article 4 of the Nigeria-Singapore BIT (2016): “[e]ach Party shall accord to investors of the other Party and to covered investments, with respect to the operation of the covered investments, treatment no less favourable than the treatment it accords, in like situations, to investors of a third country and their investments.” Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement between the Government of the Federal Republic of Nigeria and the Government of the Republic of Singapore, Nig.-Sing., April 11, 2016, https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements/treaty-files/5410/download

[14] Compare the 2000 decision in Emilio Agustin Maffezini. Kingdom of Spain, ICSID Case No. ARB/97/7, Decision of the Tribunal on Objections to Jurisdiction, January 25, 2000, paras 54–56 https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0479.pdf (deciding that MFN treatment could shorten a waiting period for arbitration and avoid recourse to local courts in Spain) and the 2005 decision in Plama Consortium Limited. Republic of Bulgaria, ICSID Case No. ARB/03/24, Decision on Jurisdiction, February 8, 2005, paras 207–223 (deciding that MFN treatment could not be used to replace ad hoc arbitration with arbitration administered by ICSID) (esp.), https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0669.pdf.

[15] . See Aguas del Tunari v Bolivia, ICSID Case No. ARB/02/3, Decision on Jurisdiction, October 21, 2005, paras 160–180, https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw10957_0.pdf.

[16] . Banro v Congo, ICSID Case No. ARB/98/7, Award, 1 September, 2000), excerpts in (2002) 17 ICSID REVIEW FILJ 380 and https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wir2016_en.pdf (2016 World Investment Report: Investor Nationality: Policy Challenges).

[17] . See, for example, Energy Charter Treaty, Art 17.1 (December 1994):“Each Contracting Party reserves the right to deny the advantage of this Part to: (1) a legal entity if citizens or nationals of a third state own or control such entity and if that entity has no substantial business activities in the Area of the Contracting Party in which it is organised.” Energy Charter Treaty, December 12, 1994, https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements/treaty-files/2427/download. See also, Mistelis and Baltag (2018).

[18] . Spyridon Roussalis v. Romania, ICSID Case No. ARB/06/1, Award, December 7, 2011, para 328, https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0723.pdf.

[19] . See Técnicas Medioambientales Tecmed, S.A. The United Mexican States, ICSID Case No. ARB/(AF)/00/2, Award, May 29, 2003, para 116, https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0854.pdf.

[20] . SGS Société Générale de Surveillance, S.A. Pakistan, ICSID case No ARB/01/13, Decision on Jurisdiction, August 6, 2003, para 168, https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0779.pdf.

[21] . SGS Société Générale de Surveillance S.A. Republic of the Philippines, ICSID Case No. ARB/02/6, Decision on Objections to Jurisdiction and Separate Declaration, January 29, 2004, para 128, https://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/ita0782.pdf.

[22] . All four drafts have received comments from the public, but, more importantly, from the Contracting States — see https://icsid.worldbank.org/en/Pages/resources/ICSID%20NewsLetter/January%202019/States.aspx.

[23] . See Working Group III: Investor-State Dispute Settlement Reform https://uncitral.un.org/en/working_groups/3/investor-state.

[24] . See Working Group III: Investor-State Dispute Settlement Reform https://uncitral.un.org/en/working_groups/3/investor-state.

[25] . Forthcoming at https://www.arbitration.qmul.ac.uk/research/.

[26] . SADC 2012; Indian Model BIT, Art 15 (2) (2015).

[27] . See the Comprehensive Economic Trade Agreement, Art. 8.29, EU-Canada, October 30, 2016.

[28] . See, UN General Assembly, “Declaration of the High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Rule of Law at National and International Level”, Resolution No. 67/1, UN Doc. A/Res/67/1, September 24, 2012.

[29] . G20 Guiding Principles for Global Investment Policymaking, 2016, para V.

[30] . Ibid, para VIII.

[31] . Forthcoming in https://www.arbitration.qmul.ac.uk/research/.

[32] . International Investment Agreements Navigator, https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements/by-economy.

[33] . Ibid, para VIII.

[34] . Forthcoming in https://www.arbitration.qmul.ac.uk/research/.