Many of the major challenges of the twenty-first century—including the current dissatisfaction of population groups who feel excluded by globalization and technological advancement—may be viewed as a “decoupling” of economic and social prosperity. In this policy brief, we present two new indices of wellbeing—solidarity (S) and agency (A)—to be considered alongside the standard indices of material gain (G) and environmental sustainability (E). Together, the four indices (SAGE) form a balanced dashboard to evaluate wellbeing, which could provide an empirical basis for mobilizing action in government, business, and civil society to promote the recoupling of economic and social prosperity. This new framework can also be used to analyze and evaluate the performance of countries in dealing with the COVID-19 crisis. We suggest that compliance with containment measures, which is vital for combatting any global pandemic, will be high and relatively easy to implement if governments ensure that fundamental human needs are satisfied. In particular, solidarity within and between groups must be high and individuals must be empowered and ready to help one another.

Challenge

We are living through an unprecedented crisis; the COVID-19 pandemic has caught governments around the world off guard. The enforced social-distancing measures have affected and disrupted all aspects of people’s lives. Further, the social and economic impact of the outbreak responses will have long-lasting consequences around the world. In particular, self-isolation measures have drastically changed people’s social lives—from the way they work to their interpersonal relations. The global community must develop policy measures to respond adequately to these circumstances. In addition to the current crisis, other major challenges of the twenty-first century must be tackled. These include climate change, environmental degradation, social and political fragmentation, and global and national governance crises. Many of these challenges arise from a decoupling of economic and social prosperity. While GDP per capita, the conventional measure of economic prosperity, has grown reasonably steadily over the past four decades, this growth trend does not appear to have been matched by social prosperity, in terms of an increasing sense of wellbeing within thriving societies. In addition, this economic growth has not been environmentally sustainable, resulting in further adverse effects on social prosperity. National, ethnic, and religious conflicts persist globally. In addition, there is rising dissatisfaction among large population groups that feel excluded by globalization and technological advancement—in both developed and developing countries. These phenomena provide further evidence for the decoupling of economic and social prosperity. Tackling the major challenges of our times will involve confronting the paradox of growing economic activity in an integrated global economy, amid ongoing tensions arising from fragmented societies and polities.

A major problem with tackling the decoupling of economic and social prosperity is that politicians are far more sensitive to economic prosperity than social prosperity. For example, when French President Emmanuel Macron taxed fuel to encourage the country’s transition to green energy at the end of 2018, he did not expect thousands of citizens to march through the streets in yellow vests. He apparently had neglected the possibility that achieving economic prosperity through “green growth” may leave large segments of voters personally disempowered and socially alienated. The same holds true for the massive protests in Chile, which began with a subway fare hike or those in Lebanon, which were triggered by a WhatsApp tax.

The sense of disempowerment and social alienation is experienced among many significant population groups in advanced and emerging economies, from inhabitants of America’s “rust belt” and Britain’s small towns to Africa’s unemployed youth. In short, in many countries around the world, economic prosperity, environmental sustainability, and social prosperity are no longer aligned. If peace and prosperity are to be assured, the governance systems at various levels—local, regional, national, and global—must be reshaped with the aim of recoupling economic and social prosperity.

Proposal

We propose the implementation of the “Recoupling Dashboard,” which will provide a new theoretical and empirical basis for assessing wellbeing, beyond GDP (Lima de Miranda and Snower 2020). It sheds light on the decoupling process and provides an empirical basis for mobilizing action by government, business, and civil society to promote a recoupling of economic and social progress. Given that the purpose of government and business is to promote the public interest, the Recoupling Dashboard is a step toward suggesting that government and business decisions be based on assessments—not only of their impact on GDP and environmental sustainability but also on solidarity and agency.

The central conceptual insights of our analysis rest on the following three claims:

(i) Human wellbeing is achieved not only by satisfying one’s preferences for the consumption of goods and services but also by pursuing and achieving value-driven purposes.

(ii) As the success of human beings is built largely on cooperation and niche construction, humans have evolved motives to socialize (particularly in groups of limited size) and use their abilities to shape their environment.

(iii) Consequently, personal empowerment, and social solidarity have become fundamental sources of human wellbeing.

Our sense of wellbeing arises from the processes of natural and artificial selection. It includes not only the satisfaction of tastes and appetites through consumption but also the pursuit of purposes and values, driven by motives. This differentiates our approach from existing measures of wellbeing that adjust or supplement GDP—such as the Measure of Economic Welfare, Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare, or Green GDP. These measures are tied closely to the notion of “the greatest happiness of the greatest number”—that is, Benthamite utility maximization, whereby social welfare is simply the sum of individual utilities. Even indicators that aim to assess wellbeing independently of GDP, by measuring the achievement of basic human capacities, such as the Human Development Index, have individualistic, preference-satisfying foundations. Our proposed Recoupling Dashboard relates to the pursuit of human purposes through the engine of psychological motives.

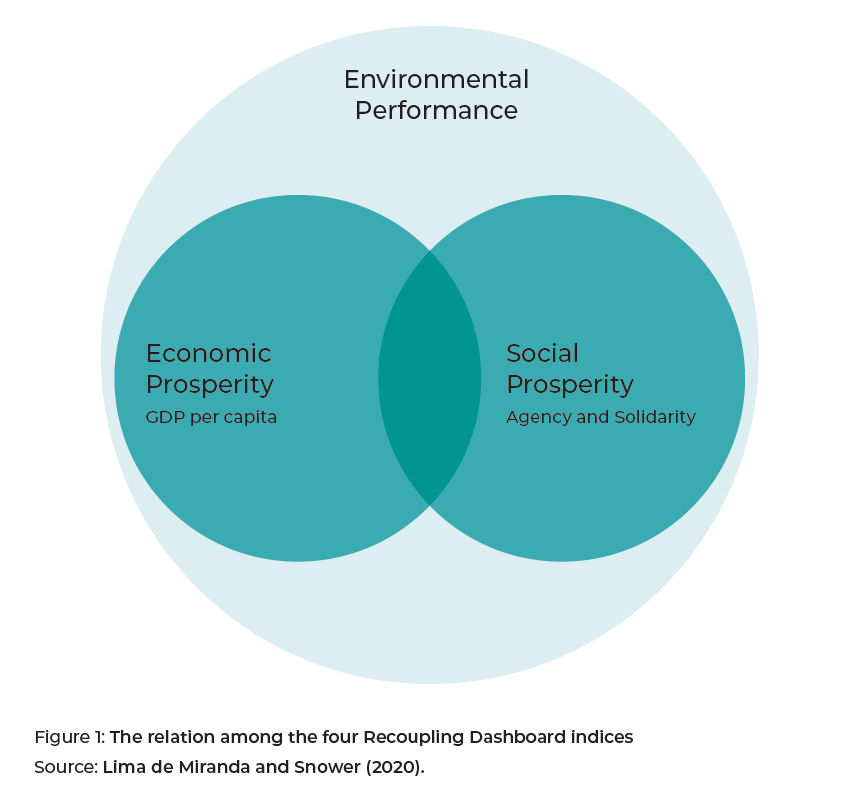

On this basis, we examine two new, innovative indices—agency and solidarity— together with economic prosperity and environmental sustainability, to gain a more balanced and profound understanding of wellbeing. Our agency index involves people’s need to influence their fate through their own efforts and is measured across five components: “Labor market insecurity,” “Vulnerable employment,” “Life expectancy,” “Years in Education,” and “Confidence in Empowering Institutions.” Our solidarity index covers the needs of humans as social creatures, living in societies that generate a sense of social belonging. With respect to social belonging, solidarity may be considered synonymous with “social cohesion” and “social inclusion.” Our solidarity index is measured using three components: “Giving Behavior,” “Trust in other people,” and “Social support.”[1] The relation among the four indices is illustrated in Figure 1.

The economy and the society are embedded in the natural environment. Thus, in Figure 1, the circle denoting “economic prosperity” (measured by GDP per capita) and the circle denoting “social prosperity” (measured by our agency and solidarity indices) are placed within the circle denoting “environmental sustainability.” In well-functioning socio-economic systems, the economic-prosperity circle largely overlaps with the social-prosperity circle, that is, the incentives, motives, and attitudes (including trust, social support, economic security, etc.) that people need to conduct economic transactions are the same as those that promote social prosperity. For an economy that grows (in terms of GDP per capita) while its citizens are mired in dissatisfaction and conflict, the economic-prosperity circle does not overlap with the social-prosperity circle. For an economy that grows in an unsustainable manner, the economic-prosperity circle expands, while the environmental-sustainability circle shrinks.

We argue that agency and solidarity—alongside economic prosperity and environmental sustainability—cover fundamental human needs and purposes, applicable to all cultures. Compared to simply maximizing economic output, people achieve a wider sense of wellbeing when they meet their basic material needs, feel securely and meaningfully embedded in society, have the power to influence their circumstances in accordance with self-determined goals, and are respectful of planetary boundaries. Failure to achieve any of these ends is associated with suffering. The inability to meet basic material needs signifies extreme poverty; lack of agency, a lack of freedom, self-expression, and self-determination; failure to achieve social solidarity, loneliness and alienation; and living unsustainably, robbing future generations (as well as others in the current generation) of the opportunity to lead flourishing lives.

The four goals—agency, solidarity, economic prosperity, and environmental sustainability—are not consistently substitutable for one another. Generally, the gains from agency and solidarity cannot be converted into temporally invariant money terms, in which economic prosperity is measured. In order to thrive, people must satisfy all four purposes: their basic material needs and wants, their desire to influence their destiny through their own efforts, their aim for social embeddedness, and their need to remain within planetary boundaries. Agency is valueless when one is starving, consumption has limited value when one is in solitary confinement, and so on. Furthermore, the gains from agency, solidarity, economic prosperity, and environmental sustainability are different in kind and, thus, are not readily comparable.

Therefore, our indices of agency, solidarity, economic prosperity, and environmental sustainability must be interpreted as part of a dashboard. Just as the dashboard of an airplane measures magnitudes (altitude, speed, direction, fuel supply, etc.) that are not substitutable for one another (e.g., correct altitude is not substitutable for deficient fuel), our four indices are intended to represent separate goals. Only when a country makes progress with respect to all four goals can it be considered to have met a broad array of basic human needs and purposes.

The Recoupling Dashboard includes data from more than 30 countries[2] for the period 2007–2018. Summarized on an X-Y plane, the Recoupling Dashboard provides a visualization of how the relationship between the four dimensions varies through time and across countries. Our data show that solidarity and agency develop differently over time and across countries compared to the indices of GDP per capita and environmental sustainability.

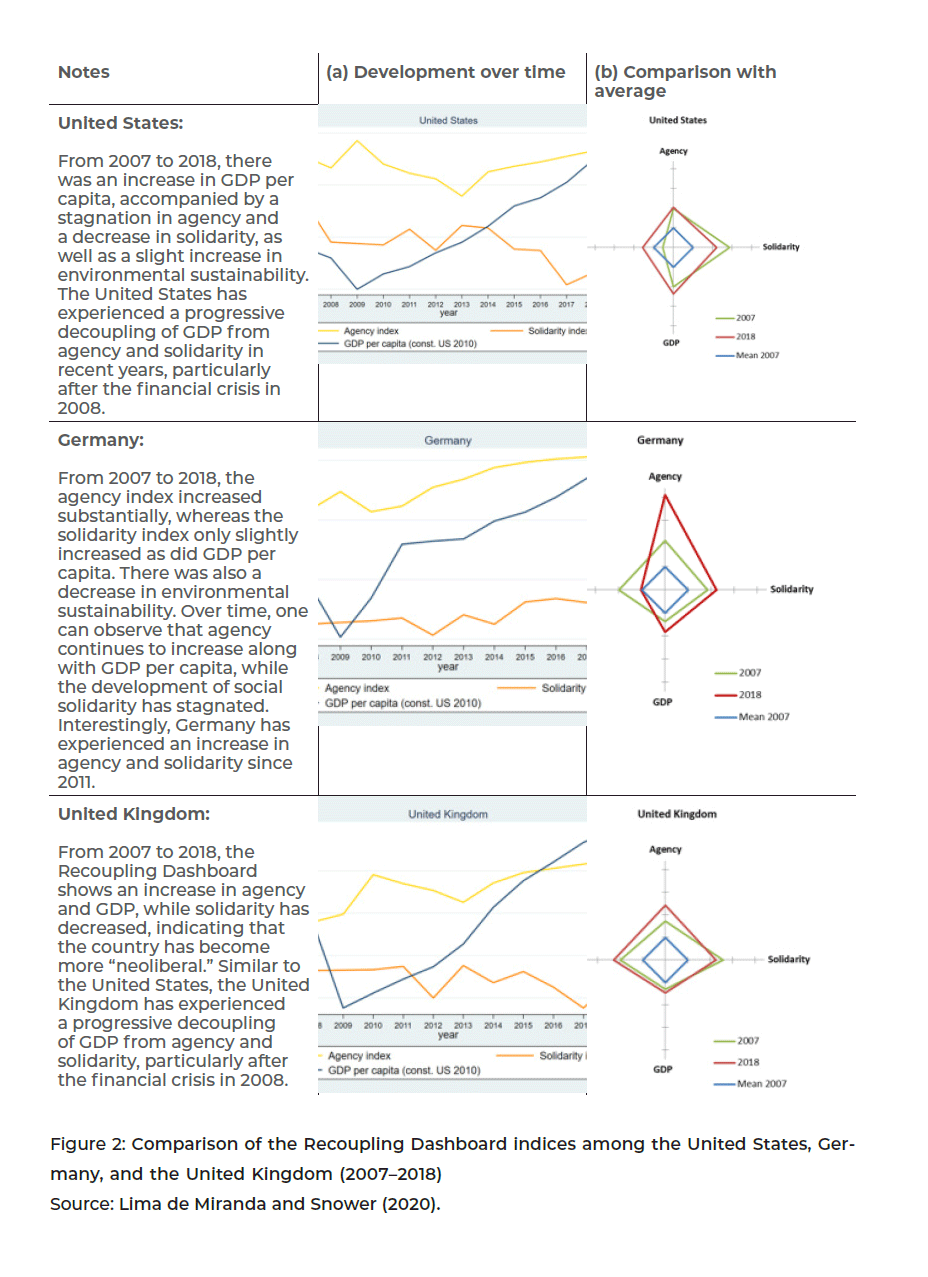

Countries with a high GDP per capita do not necessarily have high solidarity or agency. In fact, many countries with an increasing GDP per capita show a substantial decrease in the solidarity index over time. Such a disconnect is an indication of a decoupling of economic and social prosperity. In Figure 2(a), the Recoupling Dashboard indicates that solidarity and agency follow time paths that are distinct from GDP per capita.

It can be argued that, to some extent, social expenditure can crowd out personal giving (Inglehart 1997), a difference that might become visible in collectivist nations, as opposed to individualist nations. The relationship between institutions, state capabilities, and informal social ties and networks is complex (Johnson et al. 2017). In this policy brief, we define social solidarity as a sense of belonging within social groups that may be nested within larger social groups pursuing complementary ends. Five Scandinavian countries are among the ten highest-ranking countries for our solidarity index (in 2018), which implies that a well-developed welfare state and social solidarity can complement one another. In addition, our results show a positive correlation between our agency and solidarity indices. This suggests that if individuals are empowered, are able to help themselves, and are free to redirect their efforts in the context of their social groups, social solidarity may be strengthened.

In Figure 2(b), the baseline square (in blue) represents the average values of the four indices across the countries in the base year (2007). A comparison of the green and red lines shows how a country developed over the past decade in each of the four dimensions. Comparison with the blue square facilitates convenient cross-country comparison.

We observe that the time series and cross-section evidence indicate that solidarity and agency are distinct from economic prosperity and environmental sustainability.

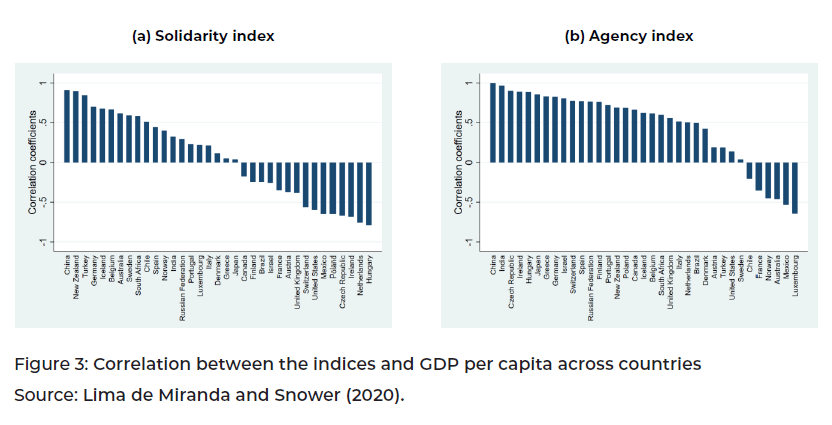

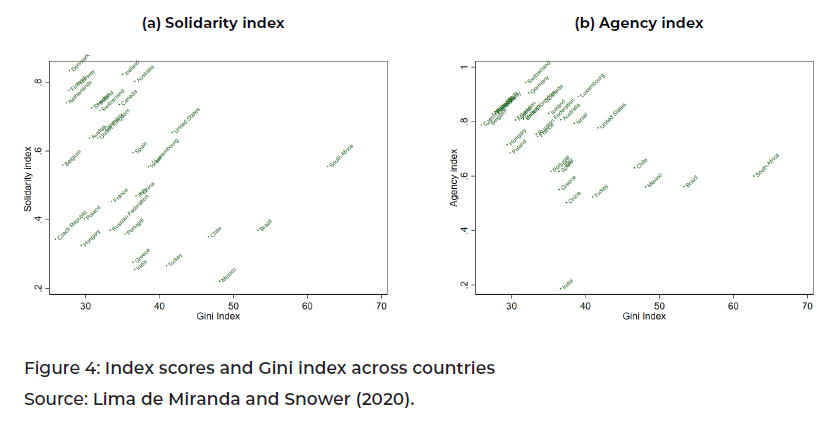

The degree to which solidarity and agency are correlated with GDP per capita varies across countries (Figure 3). Furthermore, we find suggestive evidence that inequality does not capture the phenomena of solidarity and disempowerment (Figure 4).

Our analysis indicates that globalization may be expected to improve welfare only if it is accompanied by policy measures that strengthen social communities, counteracting the decline in solidarity and agency as experienced in many Group of Twenty (G20) countries. Economic policies at the supranational level must not be implemented independently of those at the microeconomic level because there is a crucial mesolevel of social groups at which important human needs and purposes are satisfied. The G20, as a multinational forum, has unique capabilities to set global agendas and influence global norms. Therefore, it is well-placed to develop a framework for multilevel governance that encourages the recoupling of economic and social prosperity, globally.

The Recoupling Dashboard offers a new approach for the evaluation of human wellbeing. With further development, it can become a powerful tool to assess how decisions by governments and businesses affect human wellbeing. Currently, policy measures are evaluated primarily in terms of their impact on GDP. Similarly, business decisions related to production, employment, and future investments are made primarily to maximize shareholder value.

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, this new framework can also provide a more balanced assessment of the performance of countries in dealing with the COVID-19 crisis, along with its long-lasting consequences. One example in this regard is the compliance with containment measures. In order for pandemic containment to be efficient, compliance with the implemented rules is key. We suggest that compliance will be higher and relatively easier to implement if governments ensure that fundamental human needs are satisfied. In particular, solidarity within and between groups must be high and individuals must be empowered to help themselves, as well as be given the freedom to redirect their efforts in the context of their social groups. This would strengthen their social solidarity.

The T20 calls on the G20 to put fundamental human needs at the core of its policies. This includes endorsing a more holistic picture of human wellbeing. This can be achieved by including agency and solidarity in the regular reporting of national statistics and using these measures as a basis for policymaking. In addition, the contribution of the private sector should be harnessed by enabling responsible actors through several channels. Examples of these channels are: promoting the adoption of mission-oriented purpose and stakeholder-inclusive governance and harmonizing and disseminating accurate and comprehensive reporting of the private sector impact on social development and externalities.

The Recoupling Dashboard is a step toward reshaping governance systems, in both government and business, with the aim of recoupling economic and social prosperity.

Disclaimer

This policy brief was developed and written by the authors and has undergone a peer review process. The views and opinions expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the authors’ organizations or the T20 Secretariat.

References

Inglehart, Ronald. 1997. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic,

and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Johnson, Phil, Michael Brookes, Geoffrey Wood, and Chris Brewster. 2017.

“Legal Origin and Social Solidarity: The Continued Relevance of Durkheim

to Comparative Institutional Analysis.” Sociology 51 (3): 646–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038515611049.

Lima de Miranda, Katharina, and Dennis J. Snower. 2020. “Recoupling Economic and

Social Prosperity.” Global Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.1525/001c.11867.

Appendix

[1] . The data used are exclusively from external sources, such as the OECD or the World Bank

[2] . These countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, India, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Russian Federation, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States.