Informality has been a persistent feature of Arab economies. In recent years, the shift to informality has been on the rise, featuring evolutions that make its negative impact even harsher on the society and the economy.

We approach informality from the worker’s perspective, starting with the necessary preconditions for specific policy recommendations. The proposal emphasizes the importance of combining the right incentives and sensible checks and balances.

The incentives typically work on two parallel tracks: slowing down the pace of informality and tackling the stock through a set of well-integrated policies.

Challenge

Informality has been a persistent feature of Arab economies since the late 1980s (Medina and Schneider 2018). A typical country in the region employs about 60 percent of its workers and produces about 30 percent of the GDP informally (ILO 2018a; Medina and Schneider 2018). Informality is on the rise and many Arab countries are shifting from regular to irregular informal work (Assaad and Krafft 2013).

While this analysis focuses on Arab countries, the challenge of informality and the solutions recommended are relevant to the entire world.1 It is also of particular importance for Group of Twenty (G20) countries as it is closely associated with unemployment and the future of decent work. Both these issues are on top of the agenda for the T20s in 2015, 2016, and 2018.

In the 2019 G20 Summit, informality was explicitly mentioned, as Ministers of Labor and Employment of G20 countries clearly stated that youth employment in the informal sector was increasing in all countries. The way in which informality has been addressed in previous G20 Summits, however, has neglected the multidimensional and complex characteristics of informality (G20 2018; T20 2018). This policy brief attempts to bridge this gap by providing a set of comprehensive, well-integrated, practical, and evidence-based policies that address the core aspects of informality.

Informality has devastating effects at the macro and micro levels, which manifest as follows:

1. Tax evasion owing to informal practices accounts for 50 percent, 70 percent, and 50 percent of the total tax revenues in Palestine, Lebanon, and Tunisia, respectively (Jaber and al-Riyahi 2014). This implies a large number of free riders (Loayza 1996; Johnson, Kauffman, and Shleifer 1997).

2. Informality is strongly associated with lower productivity and reduced economic output. The potential of the growth of informal enterprises is stymied by the lack of access to capital, land, training, technology, and limited market access nationally and internationally (World Bank 2014a, 2019a).4

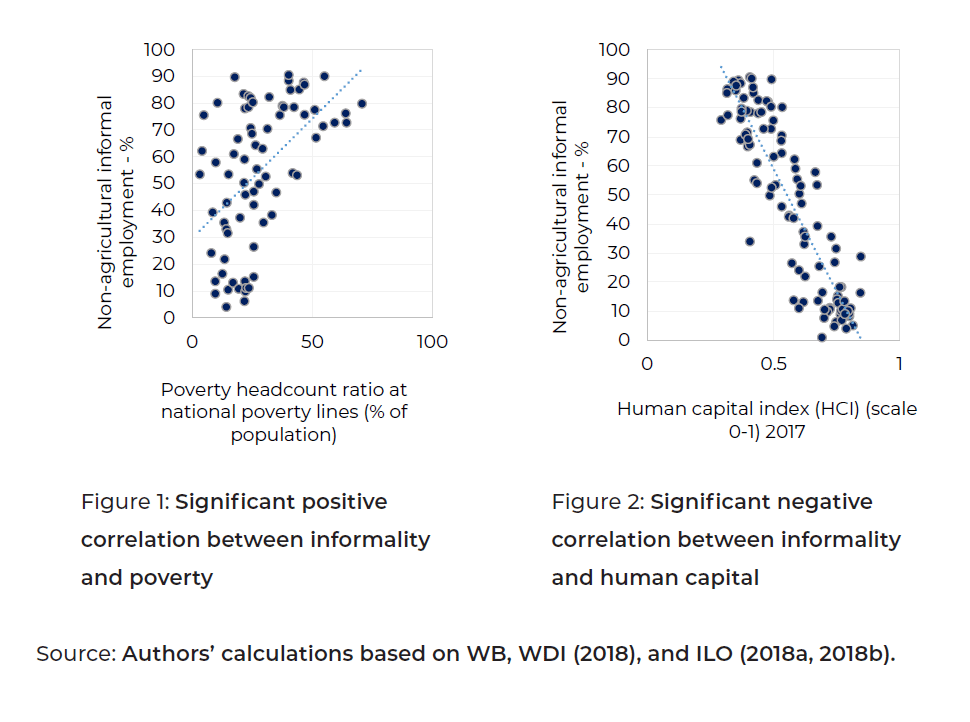

3. Informality is largely associated with weak human capital, vulnerability, inequality, and poverty as seen in Figures 1 and 2. Even though the direction of causality between informality and poverty is still unresolved, there is strong evidence that causality goes in both directions.5, 6, 7

4. Informality is closely associated with political and social instability. The association among poverty, irregularity, and informality makes societies prone to all kinds of social ills (Arab NGO Network for Development 2016).

5. The lack of decent employment is the main reason for illegal international migration (Villarreal and Blanchard 2013). The problem becomes more serious when the workers stay informal at their destination) Bosh and Farré 2013).8

6. Finally, it has been proven that informal workers are severely affected by COVID-19 (ECES 2020). The ECES has also indicated that COVID-19 has a multiplier negative effect on the economy and society as a whole, because of its effect on informal workers.

Proposal

We propose two broad categories of solutions to change informality from a liability to an asset. Our comprehensive analysis aims to enable policymakers to identify the pros and cons of adopting these solutions and seeing the full picture, ranging from preconditions to specific policy recommendations.

1. Preconditions for successfully addressing informality range from data availability and improving conditions for formal enterprises to adopting a correct approach to informality.

1.1 Ensuring the availability of updated and precise data on informality on both employment and enterprises is essential to understand the dynamics and manifestations of informality at the national level on a yearly basis and to adapt policies accordingly.

1.2 Improving conditions for formal enterprises is the shortest route to cutting the increase in the flow of informality. This can be done by:

i. Achieving good governance and improving business

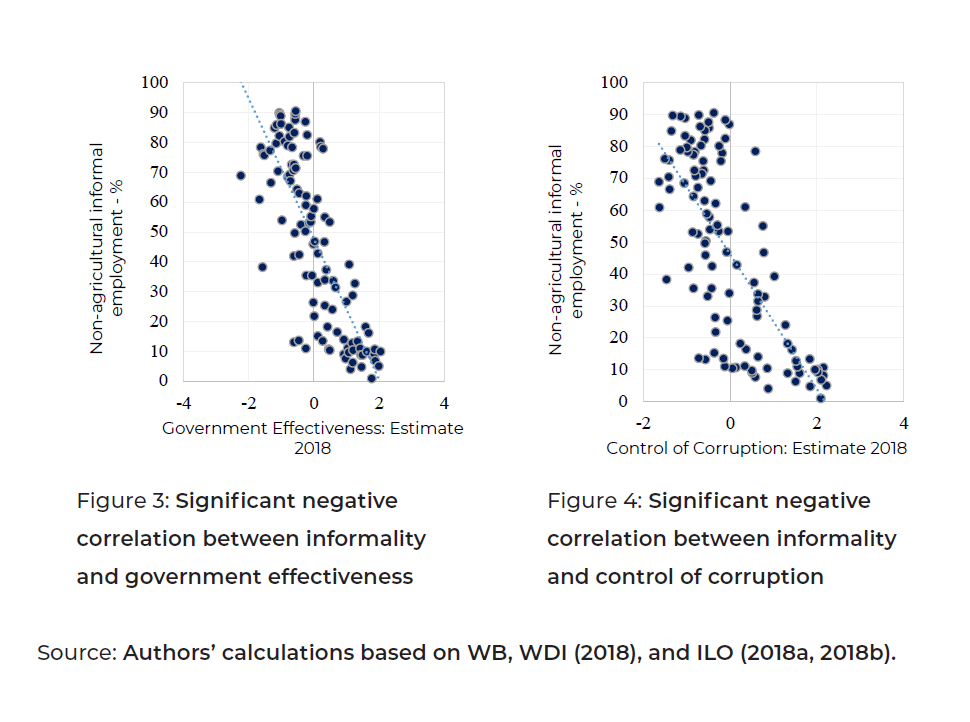

The ILO (2014) emphasized that informality is mainly an issue of governance because of the ineffective, misguided, or badly-implemented macroeconomic and social policies. Figures 3 and 4 show that informality decreases as governments achieve higher scores in governance indicators, namely government effectiveness and corruption control.

ii. Implementing sound digitization.

The World Bank (2018) showed that digitization is indispensable for efforts toward formalization to succeed.9 Proper digitization also allows for sufficient transaction traceability through a single fiscal identification number for public and private transactions (ILO 2019).10

1.3 Adopting an accurate approach to informality

i. Adopting a comprehensive reform approach that encompasses complete solutions.

Informality declined the most in countries that adopted a comprehensive strategy with well-integrated policies that cover all aspects of informality (Oviedo, Thomas, and Kamer 2009; Loayza 2018).11 Partial reforms and isolated policies will not only result in limited impact but can even worsen the situation (Fernández et al. 2017).12

ii. Changing the mindset.

Informal workers should not be perceived as criminals or as belonging to a low social class. Instead, governments must build their image as resilient entrepreneurs who keep the economy functioning even during times of crises (African Development Bank 2016).

iii. Adopting an employment-oriented approach as well, rather than an enterprise-based approach alone.

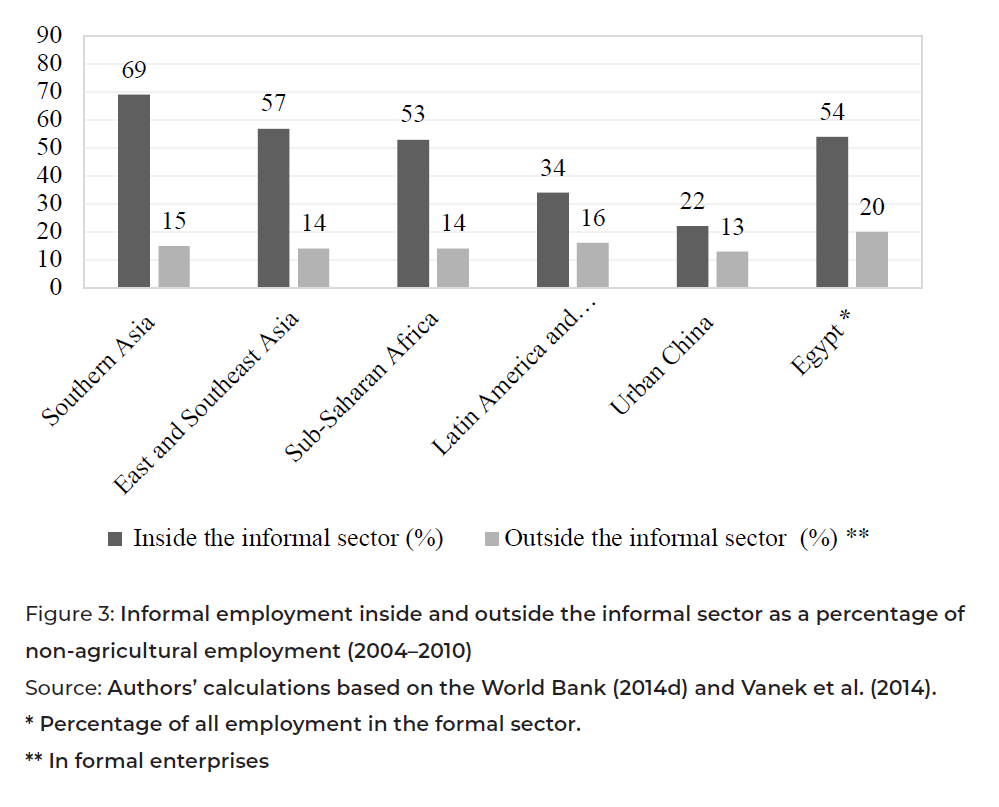

In most countries, particularly Arab countries, formalization efforts focus exclusively on informal enterprises, ignoring the fact that a sizable portion of informal employment also exists in formal enterprises as clearly identified in Figure 5.13 An employment approach captures and addresses informal enterprises and employment within the formal sector (World Bank 2014c).

iv. Building trust between the people and the government.

The absence of trust in the government makes individuals and firms follow informal rules rather than government regulations (Williams 2018). This leads to a difference between state and citizen morality (Windebank and Horodnic 2017). Governments should build trust through smart communication, by improving perceptions of fair tax collection and usage, and by reinforcing citizen engagement in the process of decision-making (Bakry 2015).14

2. Specific policy recommendations

The World Bank (2011) emphasized that for any formalization efforts to be sustainable, the productivity of both workers and enterprises should be boosted. Decent employment is a fundamental human right as recognized under Article 23 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (ILO 2013).

We propose comprehensive policies that address informality from an employment perspective. This is critical for capturing and addressing both informal enterprises and employment within the formal sector (World Bank 2014c).

We propose a set of comprehensive policies to stop the flow and tackle the existing stock of informal work in Arab countries. We also present and address the most common governmental fears that accompany each policy solution. These solutions are elaborated in the following sections.

2.1. Slowing down the inflow of informal workers

i. Creating enough private formal jobs to utilize the demographic dividend better.

Arab economies have failed to generate enough private formal jobs for the population in the working age group. Therefore, any obstacles that cap private sector potential as captured by the Doing Business Report should be totally abolished (World Bank 2019b).

ii. Promoting social mobility.

Meeting the expectations of the Arab youth in climbing the social ladder is critical to preventing them from pursuing their aspirations through informal work. International experience has showed that improved education in combination with redistributive justice and inclusive growth constitute the main channels through which governments can promote social mobility and reduce informality (Kerstenetzky and Machado 2018).15

iii. Adjusting differences in employment benefits between the government and the private sector.

The vast majority of the Arab youth aspire to work in the government sector because of its stability and benefits. In Egypt, Jordan, the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT), Lebanon, and Tunisia, 49.6 percent of the unemployed youth on average prefer to wait until they work in the government (Dimova, Elder, and Stephen 2016).16

While the rich can afford the cost of staying unemployed, most of the youth cannot. To survive, they tend to accept informal jobs during the transitional period (World Bank 2014b; ILO 2012). Therefore, bridging the gap in terms of benefits and access between government and private employment in Arab countries is expected to reduce informal employment (World Bank 2014b).17

The experience of G20 countries in this area has been very illuminating. According to the ILO (2018b), most G20 countries introduced significant amendments to their labor laws to protect all forms of employment, to restrict abusive behavior by employers who provide short-term contracts instead of permanent employment, and to guarantee a minimum income level for short-term employees. Specific examples of such measures are as follows:

- Extending legal coverage to temporary employment. The corresponding measures included limiting the number of successive fixed-term contracts authorized by law or establishing a limit on their maximum cumulative period.

- Implementing the principle of equal treatment for workers in non-standard employment is one of the most efficient ways of ensuring an adequate level of protection for informal workers. This is enshrined in the EU Directives on part-time, fixed-term, and temporary agency work and is implemented through legislation adopted by EU member States.

- Additional measures may include setting a minimum number of hours for part-time workers to ensure that they receive a minimum amount of remuneration, or establishing minimum entitlements for on-call workers, should the employment contract fail to regulate these issues.

iv. Easing labor regulations and ensuring the freedom of association.

Instead of allowing labor unions, most Arab countries tend to protect the rights of workers through rigid regulations. The rigidity of firing regulations prevents businesses from the flexible reallocation of labor during economic downturns, thus causing a significant loss of efficiency (OECD 2010; Oviedo, Thomas, and Kamer 2009). Finding themselves unable to fire, private firms have a natural incentive to employ workers informally (World Bank 2014b).

Institutional reform in that area can help reduce informal employment. Labor unions and associations will enable workers to negotiate, gain visibility, and have their rights recognized without the need for excessive state interference (European Union 2018; ILO 2014).18

International experience has showed that many developing countries around the world have allowed informal, domestic, self-employed and agricultural workers, and workers without contracts to organize themselves such as Uganda, Mauritius, and Senegal. They allowed all kinds of workers to exercise union rights. This has also been a common practice in all G20 countries (ILO 2018b). Allowing for collective bargaining has led to improvements in working conditions and, in some cases, the regularization of these workers (India) or the establishment of time-limits after which temporary contracts are converted into permanent ones (Canada and South Africa).

v. Eliminating premature entrance into the labor market.

Premature entrance into the labor market primarily takes place because of poverty in the family. Providing decent jobs and promoting social mobility will boost the wages of working adults, increase family income, and incentivize them to invest in their children instead of sending them out for informal employment (Tzannatos, Diwan, and Ahad 2016; Kerstenetzky and Machado 2018).

2.2. Tackling the existing stock of informal employment

i. Remedying the vulnerabilities of informal workers through social insurance and unemployment benefits.

Most of the Arab population is very vulnerable to shocks of illness, job loss, and disability because they lack access to social security and basic employment benefits (ILO 2019b).19 They often resort to informal work as a safety net in the short run until they find a regular job in the formal sector (Oviedo, Thomas, and Kamer 2009).*

Supporting workers during cyclical economic downturns can remedy these vulnerabilities and prevent them from seeking employment in the informal sector (ILO 2015; ILO 2019). This can be achieved through a strong safety net that combines both social and health insurance along with unemployment benefits for all types of employment, including self-employed and agricultural workers (World Bank 2019a, 2019b).20 The need for this safety net is even stronger now, given the spread of COVID-19.

Anadequate safety net also has the advantage of assisting the labor inspection administration in detecting non-complying enterprises (Kanbur 2017; World Bank 2011).21

It is important to note that such a safety net must be accompanied by an adequate system for vocational training that increases worker productivity. The heavy burden of social insurance on enterprises (41 percent of the basic wage in Egypt and 26 percent in Tunisia) discourages the commitment to formally hire workers unless they show high productivity (Assaad, Krafft, and Salemi 2019).

Meanwhile, workers themselves often prefer informal hiring because they perceive their share of social and health insurance to be high, given how far it is due for recuperation (pension) and given how poor public services are in general (Oviedo, Thomas, and Kamer 2009).

As for the experience of G20 countries, to address the gaps in legal coverage and level of social security benefits of workers in temporary and part-time employment, many of them lowered or eliminated thresholds regarding minimum working hours and/or earnings or duration of employment to qualify for benefits, which is of particular relevance for women. For instance, in Japan, mandatory coverage of part-time employees was finally extended in 2017, by reducing the monthly salary threshold for registration and by lowering the required number of hours worked on a weekly basis from 30 to 20 (ILO 2018b).

Typical areas of concern for governments in this field are insufficient financial resources to meet all needs, unemployment benefits may dis-incentivize workers from working hard, and the probability of not targeting the right person. These concerns can be mitigated easily by building comprehensive and precise databases, restricting unemployment benefits to a limited period of time, and accessing funds through tax revenues, which will automatically increase with higher productivity.

i. Boosting skills and upgrading vocational training.22

The poorly educated, whether male or female, are seemingly stuck in informality because of poor qualification. In Egypt, Tunisia, and Jordan, individuals with less than secondary education have no chance of obtaining formal jobs (Assaad and Krafft 2016; World Bank 2012).23

Therefore, Arab governments must reform their vocational education and training systems, link their outcomes to labor market needs, strike a balance between their supply and demand, and rebuild the image of vocational graduates to guarantee them the same social recognition as that of university graduates.

2.3. Checks and balances

Checks and balances are achieved through effective enforcement. This requires governments to upgrade their capacities to ensure compliance, especially in non-GCC countries. A sufficient number of well-trained inspectors should be hired and offered the right incentives based on their work.

Effective enforcement also requires building a centralized database that links social security, labor, and tax administration. With notebooks, inspectors can consult the database in real time through the Internet to verify working conditions and check whether the enterprise and its employees are registered and pay their taxes and social security contributions (Chacaltana, Leung, and Lee 2018). Non-GCC countries can draw on the experience of GCCs, especially the United Arab Emirates, which applied a similar system.

3. The role of the G20

The ILO emphasized that transitioning from informality to formality needs international coordination and the G20 is the right format for such cooperation. As the group accounts for about 90 percent of the world’s gross domestic product and 80 percent of trade, they have the coverage, the financial means, and the necessary tools to coordinate global actions against informality, particularly among Arab countries.

Many G20 countries such as Germany, South Korea, and the United Kingdom are already among the most formal economies in the world. Other countries such as Argentina, Mexico, and Brazil have implemented sound formalization policies that have significantly reduced informality over the past few decades. These countries should transfer their technical experience such as those mentioned in subsections 2.1 and 2.2 to Arab countries and help them replicate their successful polices especially in the areas of business creation and taxation, as well as the expansion of the coverage of social and health insurance to cater to all types of workers.

Since there is a strong correlation between informality and poverty, informality should be a core element in the G20’s plans to eradicate global poverty not only for social reasons but also for economic reasons. The G20 should link access to finance at preferential terms with countries that have clear programs to deal with informality.

Final Remarks

- The main objective behind addressing informality is to make the economy more efficient and to benefit from all the available resources. This lies at the core of the strategy for a more resilient, inclusive, and sustainable economy, which is required to survive COVID-19 and its repercussions, and to be able to face any future crises.

- Although the devastating impacts of informality have been recognized, few countries have developed a comprehensive and integrated approach to curb the spread of informality. Policy responses worldwide still tend to be uncoordinated, ad hoc, or limited to certain categories of workers (ILO 2014). Achieving policy coherence is expensive and challenging. However, the costs of partially addressing informality can be even higher (Galal 2004).29

- Microenterprises associated with activities in households in rural and remote areas such as handicrafts and similar activities, can and should remain informal. As they primarily fight poverty with limited contributions toward development efforts, the opportunity costs of directing resources to the formalization of these micro activities are very high. They are best dealt with through specialized marketing companies that collect their products and market them on their behalf.

Disclaimer

This policy brief was developed and written by the authors and has undergone a peer review process. The views and opinions expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the authors’ organizations or the T20 Secretariat.

References

African Development Bank. 2016. “Addressing Informality in Egypt.” https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/addressing-informality-in-egypt-15567.

Arab NGO Network for Development. 2016. “Arab Watch on Economic and Social

Rights 2016: Informal Labor in Arab Countries.” https://www.fordfoundation.org/work/learning/research-reports/arab-watch-on-economic-and-social-rights-informal-employment.

Assaad, Ragui, and Caroline Krafft. 2013. “The Structure and Evolution of Employment

in Egypt: 1998-2012.” ERF, Working Paper 805.

Assaad, Ragui, and Caroline Krafft. 2016. “Labor Market Dynamics and Youth Unemployment

in the Middle East and North Africa: Evidence from Egypt, Jordan and

Tunisia.” ERF, Working Paper 993.

Assaad, Ragui, Caroline Krafft, and Colette Salemi. 2019. “Socioeconomic Status and

the Changing Nature of School-to-Work Transitions in Egypt, Jordan, and Tunisia.”

ERF, Working Paper No. 1287.

Bakry, H. 2015. “Grappling with Cairo’s Garbage: Informal Sector Integration as a

Means to Urban Sustainability.” Master’s thesis. Center for Sustainable Development,

The American University in Cairo.

Bosh, Mariano, and Lidia Farré. 2013. “Immigration and the Informal Labor Market.”

IZA, Discussion Paper No. 7843.

Chacaltana, Juan, Vicky Leung, and Miso Lee. 2018. “New Technologies and Transformation

to Formality: The Trend towards e-Formality.” ILO, working paper No. 247.

De Soto, H. 1989. The Other Path. London: Harper and Row.

Dimova, Ralitza, Sara Elder, and Karim Stephan. 2016. “Labor Market Transition of

Young Women and Men in the Middle East and North Africa.” https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_emp/documents/publication/wcms_536067.pdf.

European Union. 2018. “Organizing Workers in the Informal Economy: Strategies for

Collective Action and Strengthening Experiences and Ideas from Researchers and

Professionals.” Research Network and Support Facility.

Fernández, Cristina, Kezia Lilenstein, Morné Oosthuizen, and Leonardo Villar. 2017.

Reconciling opposing views towards labor informality. The case of Colombia and

South Africa. Bogotá: Fedesarrollo.

G20. 2018. Digitisation and informality: Harnessing Digital Financial Inclusion for Individuals

and MSMEs in the Informal Economy. Argentina: Policy Guide.

ILO. 2012. “Rethinking Economic Growth: Towards Productive and Inclusive Arab Societies.”

https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—arabstates/—ro-beirut/documents/publication/wcms_208346.pdf.

ILO. 2013. “Decent Work is a Human Right. ILO Statement to the Third Committee

of the 68th General Assembly”. https://www.ilo.org/newyork/speeches-and-statements/WCMS_229015/lang–en/index.htm.

ILO. 2014. “Transitioning from the Informal to the Formal Economy.” https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_218128.pdf.

ILO. 2015. “Recommendation 204: Recommendation Concerning the Transition from

the Informal to the Formal Economy, Adopted by the Conference at its One Hundred

and Fourth Session.” Geneva, 12 June 2015. https://www.ilo.org/ilc/ILCSessions/previous-sessions/104/texts-adopted/WCMS_377774/lang–en/index.htm.

ILO. 2018a. Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Picture. Geneva:

International Labor Office.

ILO. 2018b. “Informality and Non-Standard Forms of Employment.” https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/how-the-ilo-works/multilateral-system/g20/reports/WCMS_646040/lang–en/index.htm.

ILO. 2019a. “Formalization: The Case of Chile.” https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_emp/—emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_725018.pdf.

ILO. 2019b. “World Employment Social Outlook Trends 2019.” https://www.ilo.org/global/research/global-reports/weso/2019/lang–en/index.htm.

Jaber, Firas, and Iyad al-Riyahi. 2014. Comparative Study: Tax Systems in Six Arab

Countries. Beirut: Arab NGO Network for Development, Social and Economic Policies

Monitor.

Johnson, Simon, Daniel Kaufmann, and Andrei Shleifer. 1997. “The Unofficial Economy

in Transition.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity no. 2: 159–239.

Kanbur, Ravi. 2017. “Informality: Causes, Consequences and Policy Responses.” Review

of Development Economics 21, no. 4: 939–961.

Kerstenetzky, L. Celia, and Danielle Carusi Machado. 2018. “Labor Market Development

in Brazil: Formalization at Last.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Brazilian Economy

edited Edmund Amann, Carlos R. Azzoni, and Werner Baer. Oxford University

Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190499983.013.28.

Loayza, Norman. 1996. “The Economics of the Informal Sector: A Simple Model and

Some Empirical Evidence from Latin America.” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series

on Public Policy 45, no. 1: 129–62.

Loayza, Norman. 2018. Informality: Why Is It So Widespread and How Can It Be Reduced.

The World Bank. Research & Policy Briefs. No. 20, December 2018.

Medina, Leandro, and Friedrich Schneider. 2018. Shadow Economies Around the

World: What Did We Learn Over the Last 20 Years? IMF Working Paper/18/17.

OECD. 2010. “Employment Outlook.” https://www.oecd.org/employment/emp/48806664.pdf.

Oviedo, Ana Maria, Mark R. Thomas, and Kamer Karakurum-Ozdemir. 2009. Economic

Informality: Causes, Costs, and Policies—A Literature Survey of International Experience.

World Bank.

The World Bank. 2011. “Policies to Reduce Informal Employment: An International

Survey.” https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3ce4/877eebcc1caae29ae0bb65cb8bffb-7d12ccd.pdf.

The World Bank. 2012. “Arab Republic of Egypt: Inequality of Opportunity in the Labor

Market.” Report, no. 70299-EG. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/315111468028441630/arab-republic-of-egypt-inequality-of-opportunity-in-access-to-basic-services-among-egyptian-children.

The World Bank. 2014a. “Arab Republic of Egypt More Jobs, Better Jobs: A Priority for

Egypt.” Report No. 88447-EG. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/egypt/publication/more-jobs-better-jobs-a-priority-for-egypt.

The World Bank. 2014b. “Striving for Better Jobs: The Challenge of Informality in the

Middle East and North Africa.” https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/445141468275941540/striving-for-better-jobsthe-challenge-of-informality-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa.

The World Bank. 2014c. “More Jobs, Better Jobs: A Priority for Egypt.” https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/926831468247461895/arab-republic-of-egypt-more-jobs-better-jobs-a-priorityfor-egypt.

The World Bank. 2018. World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education’s

Promise. Washington, DC: World Bank.

The World Bank. 2019a. “Enterprise Surveys 2019.” https://www.enterprisesurveys.org.

The World Bank. 2019b. “Doing Business 2020.” https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/688761571934946384/pdf/Doing-Business-2020-Comparing-Business-Regulation-in-190-Economies.pdf.

The World Bank. n.d. “Word Development Indicators Database (WDI).” Accessed

March 2020. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

T20. 2018. Gender Economic Equity: An Imperative for the G20. Argentina 2018.

Tzannatos, Zafiris, Ishac Diwan, and Joanna Abdel Ahad. 2016. Rates of Return to

education in twenty-two Arab countries: an update and comparison between MENA

and the rest of the world. ERF, Working Paper 1007.

Vanek, Joann, Martha Alter Chen, Francoise Carré, James Heintz, and Ralf Hussmanns.

2014. Statistics on the Informal Economy: Definitions, Regional Estimates &

Challenges. WIEGO Working Paper (Statistics), No 2.

Villarreal, Andres, and Sarah Blanchard. 2013. “How Job Characteristics Affect International

Migration: The Role of Informality in Mexico.” Demography 50, no. 2: 751–775.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0153-5.

Williams, Collin, C. 2018. Entrepreneurship in the Informal Sector: An Institutional

Perspective. London: Routledge.

Windebank, Jan, and Ioana A. Horodnic. 2017. “Explaining Participation in Undeclared

Work in France: Lessons for Policy Evaluation.” International Journal of Sociology

and Social Policy 37 (3/4): 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-12-2015-0147.